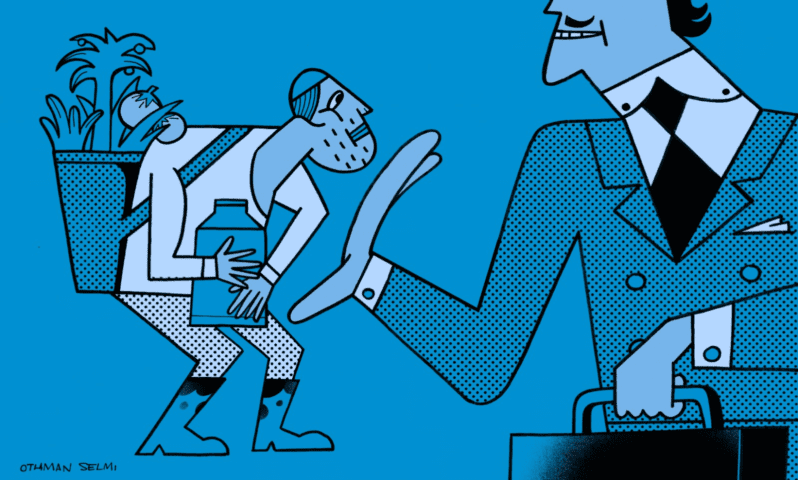

Professional and Social Transgressions Against Journalists in Tunisia

The Tunisian media scene after the revolution has been characterized by a significantdynamism that has led to a surge in the number of media institutions. However, there was not a qualitative improvement of the sector. Media personnel have remained victims of job vulnerability in some of the media institutions that have fallen under the influence of corrupt political money.

Media Institutions Under the Influence of Corrupt Money

The media in Tunisia can be divided based on ownership into public and private media institutions. The state owns public media institutions as well as the media institutions seized after the revolution. This sector employs more than 1,500 media personnel, including journalists, technicians, administrators, and workers.Labor legislation and legal employment regulations are usually respected in these institutions. Private media institutions, on the other hand, are diverse and numerous but employ a mere 250 media personnel. Most are family institutions (i.e., their capital is owned by one person and their family) and are, from an economic perspective, small or medium in size. Their owners benefit from their revenue and there is limited scope for career development within them.

Furthermore, employers in the printed press stress the fact that they face many economic difficulties, especially with regards to the absence of clear standards and criteria for how to distribute advertising content among the different papers. Another problem is distribution: to this day, influential ‘barons’ control the channels of distribution and hold thefuture of every newspaper in their hands.

Political capital has clearly succeeded in taking control of most of the audiovisual media institutions (a total of 60). Nessma TV is one prominent example of a media institution being used for political marketing, even though Tunisian legislation bans such usage. The channel’s owner, Nabil Karoui, is connected to the Nidaa Tounes party and is considered one of its leaders. The channel played a significant role in the party’s electoral campaign. After the party’selection, Nessma TV began enjoying the patronage of the political authorities, which grant it alone exclusive media interviews. On November 9, 2015, the Tunisian president went so far as to grant it exclusive rights to film the activities of the celebration honoring the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, thus excluding public media. This shocking decision provoked responses condemning the presidency’s breach of the principles of transparency and fair competitionbetween national media outlets. Objectors included the Independent High Authority for Audiovisual Communications, the National Television Establishment, the journalists' union, the Tunisian Human Rights League, and other civil society organizations.

In an attempt to improve the media scene and protect media institutions, the National Union of Tunisian Journalists is preparing to create an observatory for professional ethics, that monitors all violations and transgressions committed by establishments of the written press as a preliminary step towards creating the National Council for the Written and Electronic Press. Discussions about this council began three years ago between the aforementioned Union, the Federation of Newspaper Editors, the Tunisian Human Rights League, and the Article 19 NGO. These discussions were prompted by the need for such a council in Tunisia, especially given the absence of a body concerned with the written and electronic press. If this council is established, it will supposedly have non-preventativemoral authority, and become a reference point in the issue of the allocation of public advertising.

Regarding the Audio-Visual Communication Commission, [commission member] Hichem Snoussi says that it incorporated many precautions into the booklet of conditions [that governs the establishment and operation of media outlets]. These precautions ban employers from owning more than one television or radio station; force media institutions to employ professional journalists, particularly in their news departments; and, ban members of political parties from owning radio and television stations.

To ensure that these conditions are realized, a specialized observatory was established to monitor the extent to which media outlets are abiding by them.

Snoussi adds that, “To be honest, thus far all of these measures have not had a qualitative effect since the media can’t be built overnight, given that some of the employers themselves created a fortune in dictatorial, non-democratic systems”.

The institutional diversity and structural vulnerability that characterize the media scene has weighed heavily on journalists, who have become a professional group that is numerically important and yet suffers from marginalization.

Media Personnel in a Vulnerable Position

Private media institutions commit violations that impact negatively on the situation faced by the Tunisian media and its personnel. These violations are as follows:

Employment Contracts and Job Permanence

Employers intentionally conclude employment contracts that do not respect the legal checks contained in the Labor Code, organic laws, and the collective convention of the printed press. Usually, these contracts favor the employer’s interests and include an abundance of articles that control the journalists and limit their privileges.

From another angle, the general employment law restricts the period that a journalist may work for an institution before being made permanent to four years. This period may begin from the journalist’s first day on the job. However, most employers in the private sector fail to abide by this stipulation. They go so far as to stop journalists from working shortly before they complete their fourth year in order to circumvent the law and avoid making them permanent. Subsequently, the owners of these press institutions conclude new work contracts [with the journalists]. Thus, employers dodge the obligation to make journalists permanent.

Illegal Wages

Regarding the hiring of journalists, the Labor Code sets journalists’ wages according to their level of education and experience. However, there have been documented incidents of employers in the private sector failing to respect the minimum wage set by the general law and collective convention.

The journalists’ unions stress that the majority of the media institutions in the private sector pay their journalists no more than the minimum guaranteed wage set [by agreement] between the state and social actors, i.e., TND 250 [US$124].

Social Security and Health Coverage

Regarding social security and social and health protection for journalists, most private sector institutions in Tunisia also dodge their obligations to socially protect their workers and journalists. In particular, they dodge their obligation to allocate a percentage of their journalists’ gross wages to the National Social Security Fund. Journalists deprived of social protection in the aforementioned fund are naturally also barred from health care in public hospitals, and from receiving their post-retirement pensions. In this regard, journalists have initiated a number of court cases against their employers after having retired and discovered that the administrations of the institutions had not, over the course of their careers, paid the dues imposed upon them by law to the social security funds.

Layoffs and Arbitrary Dismissals

Arbitrary dismissalremains a sword hanging over the heads of journalists, especially junior ones. Employers use this method to arbitrarily layoff journalists without abiding by the legislation in force, and without notifying the official bodies in the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Labor Inspectorate as required by the Labor Code. Usually, employers justify firing journalists by saying that their institutions are experiencing financial difficulties that necessitate terminating a number of staff members.

Data from trade unions and from the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Directorate General of the Labor Inspectorate shows that 40 to 100 journalists fall victim to arbitrary dismissals each year. In 2015, more than 50 journalists were arbitrarily dismissed; the majority of them worked for private institutions in both the audiovisual press, and the written and electronic press.

Conclusion

The deterioration in the situation of the Tunisian media and its personnel has negatively impacted the quality of media content presented after the revolution. As a result of this situation, the Tunisian media has, apparently deliberately, been put in a tight spot so that it cannot contribute to development or cover economic corruption, on the one hand, or become involved in building democracy and defending human rights, on the other.

Last October, and in response to this situation, the Tunisian journalists’ union, in cooperation with the International Federation of Journalists, launched a 3-month long campaign to address journalists’ vulnerable employment and to rectify the situation of media institutions. This campaign includes meetings, workshops,and testimoniesinvolving people who had been fired from media institutions of all kinds and sectors. It also included educational meetings concerning the material and moral rights that domestic law guarantees for Tunisian journalists.

Furthermore, many voices in the field are calling for the establishment of an observatory to monitor the institutions that violate employment law, to publish reports to name and shame these institutions, and to resist precarious employment. This observatory will, if established, also pressure the authorities and the state to deprive such institutions of public advertising [and therefore income].

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.