Downtrodden Judges in Deteriorating Courthouses: Searching for Justice in the Dark

Since 2020, justice sector workers have been enduring a “logistical breakdown”[1] that is unprecedented in the history of Lebanese courthouses. This breakdown complicates judges’ work so much that it becomes impossible or ineffective. Every day, judges leave their homes and their private lives burdened by livelihood concerns and head to their workplaces, only for their grief to be compounded by the dire material situation of the judiciary, which now lacks the most basic, decent working conditions. “The justice sector is crumbling,” one of the judges we interviewed told us, summarizing the situation in the courthouse.

We cannot understand the crisis’ effects on the state and justice project in Lebanon without examining the day-to-day working conditions that judges have been facing since it began (although many of these material issues already existed before the crisis in varying forms and degrees). When the state of the courts deteriorates in this manner and the components of judicial work collapse, so does the judiciary’s position as an impartial public authority for resolving disputes and protecting public interest. This opens the door for other political, religious, and security authorities to improve their ability to attract citizens seeking nonjudicial and informal means of resolving their disputes, thereby strengthening their political standing at the expense of a state whose justice has become sluggish.

This article, as well as the article that preceded it, may constitute a preliminary documentation of a process of impoverishing the judiciary – as individuals and as an institution – that began several years ago, one that serves as a precursor to marginalizing it, accentuating its incapacity, and possibly replacing it with other, private means of solving people’s problems. This private-public – and then private-private – competition emerging over the authority to settle disputes could lead to the consolidation of a political system that began taking shape many years ago, one that replaces public institutions with rival and competing private authorities, just as we have been witnessing for some time in the sectors of electricity and transportation, among others. Today, this destructive dynamic has reached the judicial institution.

Our research also shows how the below-described deterioration of the material situation in the courts not only makes the judges’ task more difficult but also affects the judiciary’s symbolic distinctions, blemishing Lebanese justice with signification diametrically opposed to the collective image of justice: light turns to dark, cleanliness and purity turn to dirtiness and filth, order and organization turn to chaos, and power turns to paralysis, weakness, and resource scarcity. This inversion of public and popular perceptions of the judiciary, to the extent that the collective subconscious now associates it with all that is negative and polluted, undoubtedly has many consequences for the legitimacy of the judicial authority in the future, feeding into the aforementioned sociopolitical transformations. So, how does the situation of the courts since 2020 seem, and what do litigants see when they enter the courthouses?

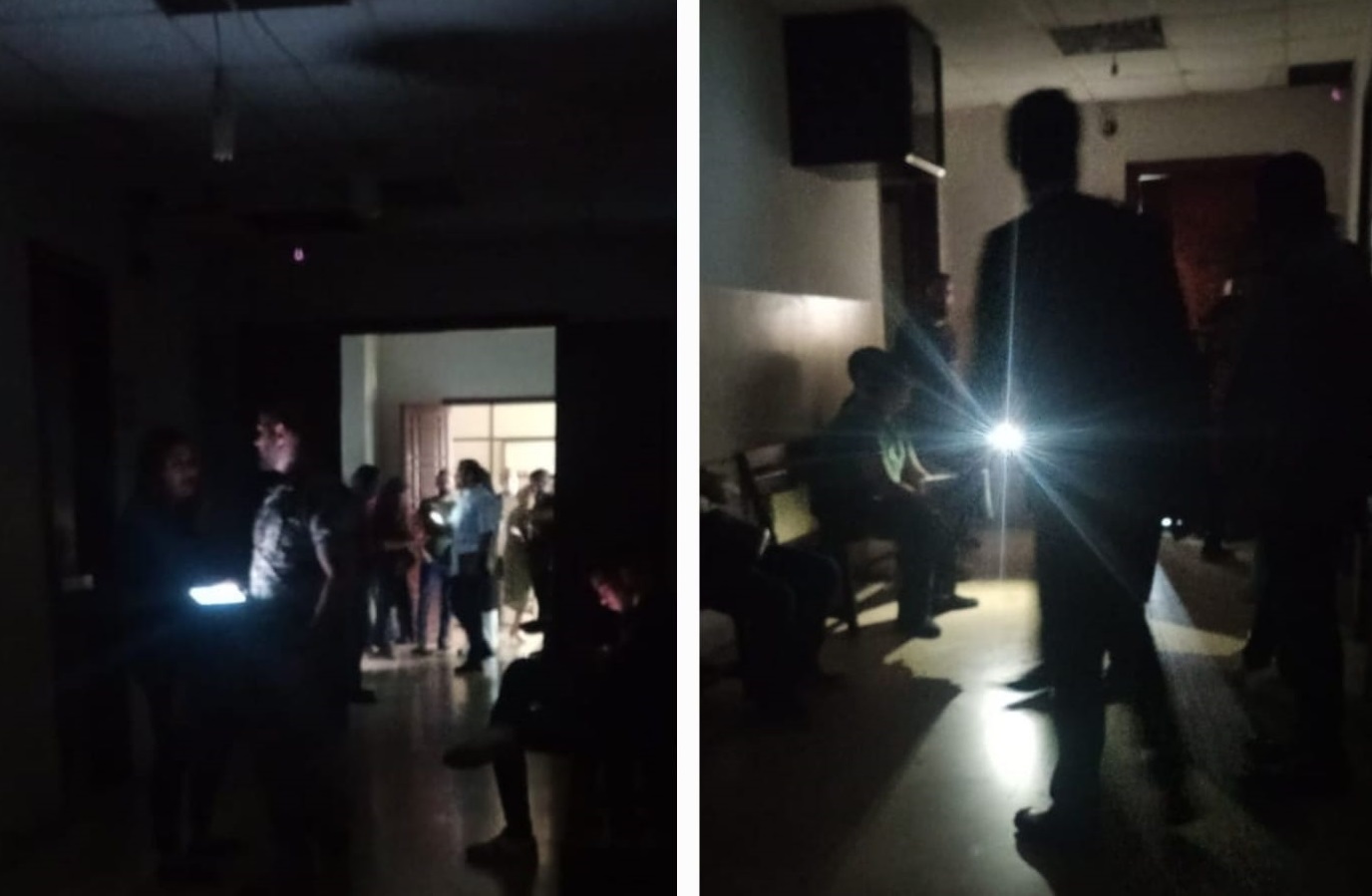

An Unlit Judiciary: Darkness and Injustice Jostle

Darkness has fallen over the courthouses in Lebanon. Lebanon’s power supply collapsed, and the electricity generators were shut down for a long time because of high maintenance costs and the inability to secure diesel. “How can I rule justly with no light or electricity?”[2] multiple judges told us, alluding repeatedly to the traditional connection between justice and light. In recent decades, architects have heeded this connection by designing and building new courthouses (e.g. the new Paris Courthouse) with glass walls, wide windows, and carefully considered internal lighting systems that flood their corridors, chambers, and courtrooms with light, thereby inspiring trust in visitors and reassuring them that justice conceals nothing from them. As for the courthouses in Lebanon, their conservative design gives no consideration to light in most places (many were never designed to be courthouses or courts), and their internal lighting has no mentionable effect, especially now that the electricity has disappeared because of a crisis that has exposed the weak government support for the judiciary and administration. The darkness governing most spaces in Lebanese courthouses screams at worried litigants, “Lebanese justice is suspicious and hides many things from you”.

“After 5PM, I can’t see the detainees in front of me in Criminal Court hearings.”[3]

In the absence of any serious overall plan to improve the situation and the inability of the judicial institutions to change it, judges have – since the crisis began – had no choice but to resort to their personal connections and acquaintances to supply their offices with electricity. Just as each judge negotiates individually with their children’s school for reduced fees (as we saw in the previous article), some judges and courts have resorted to their own resources and networks to secure electricity in their offices wherever possible. This is further evidence of the supplanting of public institutions with individual judicial initiatives that increase inequality among judges and, in this case, their risk of slipping into quid pro quo relationships with public or private parties that may have ulterior motives. We spoke with one judge who had been compelled to extend a power line from the adjacent governorate headquarters to her office, installed by her bodyguard. She controls the electricity via a circuit breaker that she flips whenever she enters or leaves her office – all at her own expense, of course. She acknowledged that some people might see this as an abuse of power, but she has no other solution as she cannot work if she does not resort to these methods. As for the hearings held outside the office, there is no way to provide them with electricity, so she has repeatedly used her phone’s light – or, more recently, a solar light now installed in the courtroom – to read her cases.

Since 2020, the ways of obtaining a few hours of electricity have multiplied, but they are all irregular, inconsistent, and even informal. The court in Aley, for example, was at one point supplied with a power line by the municipality[4] as they share the same building. However, electricity was only available in the court on Mondays and Tuesdays as nobody worked in the municipality on the other days. Hence, the judges remained at the mercy of the working hours, activity, and motivation of the municipality’s employees. In another case at another stage, the court took electricity from the adjacent gendarmerie station to illuminate a single light. As for the State Council, it is now connected to the military hospital’s electricity. Multiple judicial assistants in one courthouse also told the Legal Agenda that the electricity is only consistently turned on when the court’s first president is there. Public servants also told the Legal Agenda that the electricity is turned on only when the judges come to the building; at other times, they must do without.[5]

The absence of electricity from the courthouses is enlightening. By following the feeder lines, even when they are not carrying power, we can track the balances and relationships of power inside the world of the Lebanese state and its judiciary. Firstly, these individual or local judicial initiatives have not been hidden from official judicial and political parties; rather, they have occurred with the blessing and encouragement of these parties. We learned that when some judges turned to the Ministry of Justice to solve the electricity problem, the ministry invited them to make local contact with all the institutions that might agree to supply them with electricity, such as the district governor’s office, the army, and General Security.[6] Secondly, this situation has put the courts and judges in a relationship of electrical dependence on other institutions – such as the municipalities and security forces – that now govern, directly or indirectly, the judiciary’s work and productivity. Thirdly, the electricity issue has exposed sometimes latent forms of preferentiality and hierarchy inside the world of justice in Lebanon. It has reminded us how the first president is “more important” than the other judges, how judges are “more important” than judicial assistants, and so on. In the past, the Legal Agenda has repeatedly pointed out the danger posed by this branching inequality.

A Judiciary Buried Under Dust: Dirty Court Benches

Judges and judicial assistants complain of the escalation of the sanitation crisis in the courthouses, courts, and offices since 2020. While everyone recognizes that the courthouses were not sparkling clean before the crisis, the situation has become so bad during the last years that it undermines the image of the judge, the judiciary, and justice. How can judges rule while dust accumulates around them and wastepaper and rubbish pile up in the courts, registries, and corridors? One lawyer tells us how the judge bashfully told him, “The hearing is at the bench, but prepare yourselves: there’s filth”. He described the bench room to us as “disgusting and dirty”, with dust and chairs scattered everywhere. During our work on the Labor Arbitration Councils amidst the crisis in 2021 and 2022, we documented how the courthouses are drowning in filth that impacts litigants’ trust in, and respect for, the judiciary. The consequence is that judges and judicial assistants have assumed the burden of daily and weekly cleaning of the offices in particular. Hence, judges’ attention is now divided between matters like releasing detainees, sentencing murderers, and adjudicating commercial cases, on one hand, and wiping dust, removing rubbish, and cleaning bathrooms, on the other. Naturally, this has negative effects on the quality of judicial work.

“We take the office rubbish out in bags and throw them away, and we wipe the dust from the office.”[7]

Sanitation also constitutes a financial concern as at a certain stage, the cost of cleaning – which judges pay from their own pocket – came to consume a significant portion of their salaries, which have depreciated since the end of 2019. Some judges even expressed that because they cannot afford the additional expenses, this concern has fallen on the shoulders of the public servants, whose financial situations are also difficult. The scarcity of tap water further complicates the issue: many judges can no longer use the bathrooms at work because of the state of them. At one point, judges were forced to take drastic measures – such as not drinking water during the day, as one told us[8] – to avoid using the toilet. In Beirut, this problem prompted public servants to use the toilets at the Bar Association headquarters, the courthouse police station, or the jail. While the police stations continue to receive water, judges’ offices and courts are not among these privileged spaces in the Lebanese state.

Judges Without Ink or Paper: With, and on What, Can Rulings Be Written?

Since 2020, basic work supplies, such as paper and printer ink, have disappeared from the courts for long periods. Before the crisis, judges often purchased some of these supplies at their own expense, but they were no longer able to fill this gap once their salaries began depreciating, reaching USD200 per month at one point. Hence, they were deprived of most of the logistical and technical means necessary to complete their work.

“If the ink cartridge breaks, I get worried. I supply them because my brother gives me money. A judge who doesn’t have anyone to help him issues [hand]written rulings.”[9]

One of the most obvious things that has disappeared from the courts during the crisis is paper: registry paper, margin paper, and envelope paper. Public servants hand lawyers templates of these valuable types of paper and ask them to bring back photocopies from outside the court so that their transactions can be completed. In other cases, the public servant asks lawyers to bring printing paper with them in order to complete their transaction. In the State Council, for example, it is now common practice for a public servant to ask lawyers for paper to print (e.g. a ruling) for both them and their opponents.[10] The supplies situation improved somewhat in the second half of 2023. Besides the paper crisis, lawyers now suffer from the escalating phenomenon of “lost files”. While losing files once constituted an embarrassing problem for the public servant responsible, in recent years it has become commonplace. The crisis has also exacerbated the poor state of the storerooms: some are unlit, some are roamed by cats, rodents, and insects, and many are affected by moisture, which causes allergies and coughs for the public servants.

An Exposed Judiciary: A Growing Sense of Insecurity

Some judges are feeling increasingly insecure in their courts and offices and as though the judiciary has become fair game. Judges expressed that they feel “exposed” because of the weak security measures in the courthouses. They worriedly watch, with their own eyes, two developments that have been simultaneously occurring since 2020: the escalation of the crisis and accompanying physical, material, psychological, and social violence in public and private spaces, on one hand, and the poor condition of the security forces’ personnel and institutions and subsequent decline in their ability to protect the courthouses, on the other. Even the presence of bodyguards for judges – especially for those working in criminal justice – no longer makes them feel safe.

“If you asked my bodyguard to go down to the bottom floor and come back up, you would see him exhausted and unable to move because of his very poor physical fitness. Is this who will protect me from people with power, money, and weapons in Lebanon?”[11]

The sense of insecurity increases whenever there is an increase in popular demands for the judiciary – especially in the wake of the 2019 movement – to perform its role in punishing the people responsible for the crisis, the corrupt, and the law evaders, most of whom have power and influence. One judge working on a sensitive case even told us that he is now waiting to be assaulted when he returns home in the evening and parks his car in the dark streets.

Attempts to Circumvent the Material Shortfalls: Toward Second-Class Justice?

Today, judges, lawyers, and public servants are coming up with more and more ideas, innovations, and initiatives to circumvent the material deficiencies and increasing difficulties impeding their work in order to continue performing it as much as possible. However, we must consider the implication of this general adaptation to the extremely poor material situation created by the crisis and its effects on the institutions of justice in Lebanon. Judges and public servants’ ability to adapt to their low, unstable, and unguaranteed salaries, along with the disappearance of health and family coverage and the collapse of the components of judicial work as seen in this article, will inevitably have negative repercussions on judicial work both quantitatively and qualitatively. Glorification of judges’ patient and professional tolerance of the calamities afflicting their profession and the judicial institution, which has been a common theme since at least 2020, will not spare Lebanon’s judiciary from a palpable decline in its ability to perform its duties – an ability that was limited even before the crisis. The current situation may constitute a kind of resignation to the de facto reality, with everyone on the ground concluding that nothing will change in the short term and they must adapt and “make do”. This make-do justice could be the only justice available to Lebanon’s population for many years to come.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] Nada Ayoub, “Shahran ‘ala ‘Awdat al-Quda: ‘al-I’tikaf’ Mutawasil”, Al Akhbar, 9 March 2023.

[2] Interview with a judge, June 2023.

[3] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[4] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[5] Field survey conducted by the Legal Agenda in July 2023.

[6] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[7] Interview with a judge, June 2023.

[8] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[9] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[10] Interview with a lawyer, July 2023.

[11] Interview with a judge, March 2023.