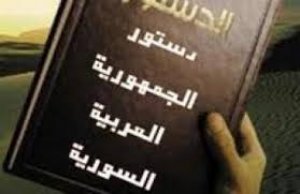

From Arabism towards a Constitution for All Syrians

In regards to the foundations and structure of the Syrian state and the formation of Syrian national identity, the issue of Arabism is of paramount importance – rivaling the issue of Islam and its influence. This is especially true in light of the profound political and social changes taking place in the Syrian arena. Some would even go so far as claiming that in the case of Syria, the influence of Islam is secondary to that of Arabism. This is based on the fact that throughout the past decades of its rule, the Syrian regime has rejected religious ideology in favor of backing the ideology of Arabism.

The latter may compensate, to some extent, for the [regime’s] lack of a religious basis for its legitimacy, given that its president comes from a religious minority that is not representative of the majority of Syria. In this regard, the Syrian regime has, throughout its rule, focused on the ideas of the Socialist Arab Baath Party (which are based on the ideology of Arab nationalism) in a fundamental way. This has led to a degree of support for Syrian Arabism such that all of its citizens are considered Arabs, in a blatant violation against, and a clear disregard for the country’s non-Arabs including Kurds, Syriacs, Armenians, Circassians, and Turkmens.

The debate over Arabism, like that on the relationship between religion and state, is not only between the Syrian regime and its opponents, but extends to debates within Syrian opposition circles. These debates have resulted in enormous differences, particularly between representatives of majority Kurdish parties on the one hand, and some Arab nationalist opponents on the other.

The Evolution of Arabism in Syrian History

As with other countries in the region, the idea of Arab nationalism developed during periods of struggle against Ottoman colonialism and French mandatory rule. It emerged as a reaction to policies of Ottomanization and French Assimilationism, and aimed to achieve unity and to support Arab solidarity. It is known that in this regard, non-Muslim Arabs played a role in the advancement of Arab nationalist thought, which inevitably brought about a decline in Islamic influence. It therefore led to the establishment of national identity on a non-religious basis, contributing to the decline of the dominant notion of the Islamic Ummah, or nation, in exchange for support for the idea of an Arab homeland [watan] that included Muslims and non-Muslims on an equal basis.

[Influential non-Muslims within the Arabism movement] included Boutros al-Bustani (1819-1883) and Ibrahim al-Yaziji (1847-1906), who were among the most notable thinkers of the late 19th century period known as Nahda. Later, Michel Aflaq (1910-1989) emerged as one of the founders of the Socialist Arab Baath Party, which brought a number of political movements to power, especially in Iraq and Syria. As for the Arabization of the state in Syria, its history dates back to October 5, 1918 when Prince Faisal bin Al-Hussein, one of the leaders of the Great Arab Revolt, entered Damascus. Once there, he announced the formation of “a pure and completely independent constitutional Arab government”.[1] The influence of Arabism persisted in Syria, as is clear from its subsequent constitutions, reaching its zenith during the rule of former President Hafez al-Assad, as I argue below.

Arabism and the Pre-1973 Constitutions

Arabism began to take effect in varying degrees during the first stages of the Syrian state, which was designated “The Arab Kingdom of Syria” in 1920. The leaders of this new entity included newly appointed King Faisal I and Hashim al-Atassi, head of the Syrian Congress that was convened on March 6 of that year. These leaders immediately began to prepare a draft Constitution consisting of 148 articles. Although it recognized Arabic as an official language (Article 3), this draft was based primarily upon equality before the law in rights and duties (Article 11), and did not specify or define a comprehensive national cultural identity for all Syrians. Furthermore, it did not impose Arabism as a means to forge integration and inclusion, as would be the case with subsequent constitutions.[2]

However, this draft Constitution was not adopted due to the beginning of the French Mandate Period in Syria with the arrival of French forces on June 24, 1920. The Mandate Period saw the recognition of the 1930 Constitution, which merely mentions “The Syrian Republic” without specifying the Arab character of the emerging state. As for the 1950 Constitution, it was adopted by the democratically formed Constituent Assembly on November 26, 1949. Despite the democratic nature of its adoption, and the focus of its provisions on the rights of citizens and the sovereignty of the state, it was the target of numerous criticisms – especially regarding its definition of the state’s cultural identity, namely, its Arabism.[3][4]

This Constitution’s Preamble includes the following phrase: “We the representatives of the Syrian Arab people…”. The phrase is repeated in the Constitution’s final section – which also points out that the Preamble “is an integral part of this Constitution”. The latter’s first article states that, “Syria is a democratic Arab Republic” and that, “the Syrian people are a part of the Arab nation”. The fourth article describes Arabic as the official language, without any mention of other languages, such as Kurdish or Syriac. Numerous sections of the 1950 Constitution are marked by an Arab nationalist ideological character, including Article 75, which concerns the presidential oath. This oath mandates a commitment “to realizing the unity of all Arab nations”.[5]

The 1950s and the period that followed witnessed a number of military coups, which were punctuated by the suspension of the 1950 Constitution and the adoption of [new] constitutional amendments, as well as the issuance of temporary constitutions that began to be dominated by Arab nationalist ideas. The 1950 Constitution was again suspended [in 1958] at the time of the unity pact with Egypt and the declaration of the United Arab Republic. At the time, an interim Constitution was adopted that remained in effect until Syria left the union in 1961. Subsequently, the 1950 Constitution was reinstated after certain amendments were added, including the designation “Syrian Arab Republic” rather than “Syrian Republic”.

In 1963, this Constitution was stricken down for the last time after the military coup known as “The March 8 Revolution”, which was led by a group of Baathist officers, including the late Hafez al-Assad. This new authority adopted a series of temporary constitutions, dominated by Socialist Arab Baath Party ideals. The last of these was the 1973 Constitution which remained in effect until 2012, a year after the start of popular protests against the dictatorship.

Arabism in the 1973 Constitution

The ideological hegemony of Arab Baathism is made clear in the 1973 Constitution, which consecrates a single party system that dominates various spheres of life. The ruling party left its mark on a number of constitutional articles, particularly the first one, which includes a number of terms related to Arabism, e.g., “the union of the Arab Republics”, “the Syrian Arab Republic”, “the Syrian Arab region”, “the Arab homeland”, and “the Arab nation”.

The Constitution’s 8th article eliminates the multi-party system with its explicit stipulation that, “the Socialist Baath party is the leading party in the society and the state. It leads a patriotic and progressive front seeking to unify the resources of the people’s masses and place them at the service of the Arab nation’s goals”. According to Article 21, “the educational and cultural system aims at creating a socialist nationalist Arab generation which is scientifically minded and attached to its history and land, proud of its heritage, and filled with the spirit of struggle to achieve its nation's objectives of unity, freedom, and socialism”.

Article 21 states, “the nationalist socialist education is the basis for building the unified socialist Arab society. It seeks to strengthen moral values, to achieve the higher ideals of the Arab nation…”. As for the Constitutional oath, in Article 7, it calls for working towards “the realization of the Arab nation’s aims of unity, freedom, and socialism”. This commitment is also applied to the armed forces and other defense organizations, which are responsible, according to Article 11, “for defense of the homeland's territory and for the protection of the revolution's objectives of unity, freedom, and socialism”.[6] Even judicial rulings are issued, according to Article 134, “in the name of the Arab people of Syria”.

The influence of this constitutional language has extended to various domains of legislative, political, social, and even economic life. One of the key aspects of recent decades has been the oppression not only of non-Arabs, but of those who are not Baathists, or do not support the ruling regime and its ideology. By way of example, one might mention the criminalization of any statement or action in opposition to the achievement of unity among the Arab regions, or opposing any of the goals of the revolution.[7] The Kurds and Syriacs have been banned from studying their language, and sometimes from speaking it. They have also been exposed to numerous forms of discrimination, including being banned from holding public office, discrimination in the workforce and in education, and the deprivation of thousands of Kurds of Syrian citizenship.

The 2012 Constitution and the Identity of the State

The 1973 Constitution remained in effect until the start of the Syrian revolution in March 2011. The Assad regime adopted a new Constitution in February 2012 in an effort to alleviate political tension, restore stability, and to guarantee that the regime remain in power.

Nevertheless, the text of the new Constitution came as a disappointment: first, it repeated the majority of what the previous Constitution contained, especially in terms of the system of governance and the possibility of Bashar Assad’s rule being renewed for two additional terms. It was also considered disappointing because of the unilateral manner in which it was drafted, and because the constitutional referendum took place without even the minimum standards of transparency; and, in the context of the repression and abuse of those who did not support the regime, the continuation of military operations, and the absence of a peaceful solution.

The text of the new Constitution preserves the ideology of the ruling Baath regime as well as its means of administering its authority, despite the removal of Article 8 of the previous Constitution (which had stated that the Baath party is “the leading party in the society and the state”). Like the 1973 Constitution, the new Constitution affirms the ideological influence of both Arab nationalism and religion.[8]

In addition, the new Constitution’s Preamble stipulates that, “The Syrian Arab Republic is proud of its Arab identity and the fact that its people are an integral part of the Arab nation. The Syrian Arab Republic embodies this belonging in its national and pan-Arab project and the work to support Arab cooperation, in order to promote integration and achieve the unity of the Arab nation.” The Constitution adopts the same vocabulary of Arabism presented in the 1973 Constitution, with the addition of phrases such as “Arab civilization”, “the Syrian Arab role”, and “the heart of Arabism”. Article 4 confirms that, “the official language of the state is Arabic” without reference to other languages or the cultural rights of those who speak them. The character of Article 7 concerning the constitutional oath, also draws upon the previous Constitution: it calls for a commitment “to act in order to achieve…the unity of the Arab nation”.

It is true that regarding Arabism as an ideological foundation for including all inhabitants of the Arab world did succeed in uniting the ranks of Christians and Muslims, especially in the mid-19th century and during times of anti-colonial struggle. However, this ideology was later proven to be incapable of promoting the principle of citizenship, and realizing the integration of non-Arab minorities. To this day, its goals have not been achieved. In fact, Arabism brought considerable oppression upon the region’s inhabitants, under the banner of slogans raised by political parties in the name of those goals.

Likewise, the effects of religious legislation and the establishment of a link between religion and the state, have led to a violation of the rights of non-Muslims, as this author has demonstrated previously.[9][A1] It follows that the ideology of Arabism resembles what can be called “Islamism”, in that the former has contributed to the violation of the rights of non-Arabs, with a negative effect on their integration; while non-Muslims -or even non-Islamists- have suffered from the second.

In this context, voices are being raised in a call to strip the state of ideology, whether religious or nationalist, in favor of establishing a civil state that provides services to citizens regardless of their religious or racial affiliation. This matter applies, too, to those demanding secession, like some Kurds – as the establishment of a state based on race or ethnicity will lead, in the end, to discrimination against non-Kurds who will be treated as second-class citizens.

Thus, the question arises about the nature of a comprehensive national identity for Syrians, and the extent to which it is possible to strengthen the trend towards patriotism based on human citizenship. This would entail affiliation with Syria, first and foremost, with respect for its ethnic and religious pluralism. It would include, as well, support for a shared human enterprise towards the peoples of the Arab region, and the development of mutual cooperation among them, as is the case in the agreement of the countries of the European Union.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] Muhammad Jamal Barout, the Syrian General Conference (1919-1920): The First Syrian Constitution, in “The Constitution in Modern Arab Thought: Histories and Issues”, Tabayan (newspaper), No. 3, Vol. 1, Spring 2013, p.23-24.

[2] Ibid., p.39.

[3] This was the opposite of what happened within the 1930 Constitution, whose adoption was fundamentally based on the desire to break away from French Mandate control.

[4] It should be noted that numerous voices among the Syrian opposition call for a return to the 1950 Constitution; we disagree with them on this point. It is not only the fact that this Constitution is dominated by a nationalist and religious ideology that provides cause for its rejection, but also the fact that it was drafted and adopted before Syria had ratified a number of international human rights conventions. Therefore, today what is needed is the drafting of a new constitution that would consecrate Syria’s commitments to these conventions, and conform to the spirit of the age and to various political developments that Syria has witnessed lately. It should also include a constitutional guarantee of avoiding the repetition of systematic human rights violations that have been witnessed over the past decades, such as forced disappearances which are complicated by the the immunity of the security apparatus.

[5] See also Article 46, which includes similar language concerning the oath for members of the legislature.

[6] This is the oath taken by each president of the Republic, the prime minister and his deputies, the ministers and their deputies, and members of the People’s Council. See the following Constitutional articles: 63, 90, 96, 116.

[7] For example, see the law on opposing the goals of the revolution, issued by Legislative Decree No. 6 on January 7, 1965, as well as the mandates of the Supreme State Security Court, created by Decree No. 47 of 1968.

[8] See: Nael Georges’, “Controversial Issues in the Syrian Constitution (1): Towards a Constitution for all Syrians”, The Legal Agenda, August 25, 2014.

[9] Ibid.