Electoral Meddling: Bottom-Up Construction According to Saied

On Monday, 24 October 2022, hours before the close of the period for receiving candidacies for Tunisia’s legislative elections scheduled for December 17, the Electoral Commission announced that it was extending the deadline by three days. The commission provided no reasons, but evidently, the candidacies that had arrived were insufficient because of failing to meet the endorsements requirement. On Monday evening, the candidates numbered 1,249 – a rate of six men and one woman per electoral district – although hundreds were expected to be excluded by the commission for not meeting requirements.

This occurred after President Kais Saied declared – on October 7 – that the electoral legislation he had unilaterally revised three weeks earlier “had not achieved its goals.” Endorsements, he said, had transformed into “a market where consciences are bought and sold” and as a result, amending the legislation was a “sacred national duty.” After that statement, everyone expected a new decree changing the rules of the electoral game already underway. Yet in the end, the sultan-president apparently changed his mind without explicitly announcing so or explaining why. Meanwhile, Facebook pages close to ruling circles spoke more frequently of the president’s intent to delay the elections. For its part, the Electoral Commission was initially optimistic when it considered its reception of 326,000 endorsements for over 1,700 potential candidates a sign of a high election turnout. But the commission’s later decision to extend the deadline for candidacies was an implicit acknowledgement that it had miscalculated. To this day, the commission is still contradicting itself over whether parties may participate in the elections. The country’s main political forces have already decided to boycott what they aptly deem a folly aimed at excluding them and producing a parliamentary chamber composed of loyalists in a political system that the president tailored to his delusional project and autocratic inclination.

The Endorsements Market: Flaws Finally Admitted

Just as he did when drafting his constitution, the president issued the decree revising the Electoral Law unilaterally. It contained the choices that he had been advocating since the first years following the revolution and that gradually formed into the “bottom-up construction” project. The president did not listen to the criticisms arguing that voting on individuals in small districts creates more scope for corrupt money to buy votes. Weakening the political dimension of electoral competition in favor of struggle among individuals standing for their own interests necessarily encourages other ties, namely familial, tribal, and clientelist ones. Likewise, concentrating the “financial investment” in a narrow geographical area renders it more effective, as established by numerous academic studies and comparable experiences, particularly in similar societies such as Egypt and Jordan.[1] The president turned a deaf ear to these criticisms and, via his decree, strengthened the privilege granted to capital-holders by canceling public funding and adding the condition of obtaining 400 signed and authenticated endorsements, with half coming from men, half from women, and one quarter from youth. It was clear that this number of endorsements, under these minute conditions and with endorsers having to commute to authenticate their signatures, would be difficult to supply, especially in districts comprising just a few tens of thousands of constituents, and that buying and selling were therefore likely. But in the president’s mind, electoral corruption is associated exclusively with political parties. He believes that they “live off” the democratic transition via public funding and that abolishing their intermediate role will cleanse politics and enable the people to express its “true” will.

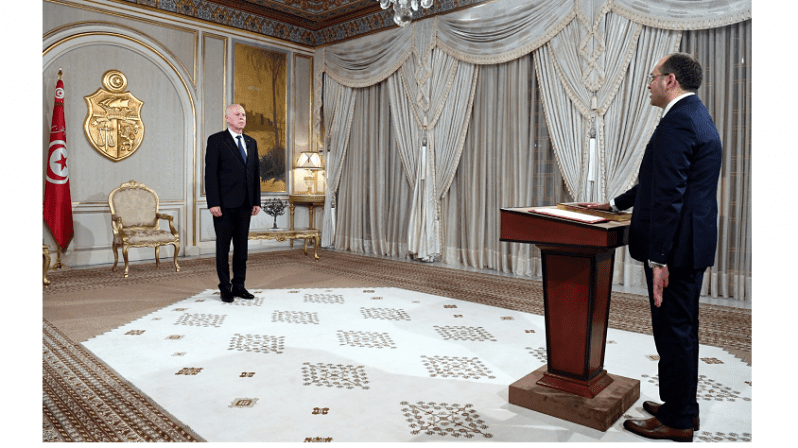

However, as expected, the president’s vision clashed with reality. As soon as the race to collect endorsements began, numerous testimonies of buying and selling emerged. As reported in the media and social media, the price of an endorsement ranged from TND10 to TND50 [USD3 to USD15]. The candidates of factions affiliated with the president were among the first to denounce this practice, as many – at least initially – struggled to compete with capital-holders in this market. The pro-Saied parties, such as the People’s Movement, the Tunisia Forward Party, and the July 25 Movement, fared no better. Their leaders appeared in the media to denounce the corruption and the buying and selling marring the endorsements race. The Electoral Commission, too, spoke of numerous transgressions and pledged to prosecute them in coordination with the Public Prosecution. Subsequently, when the president received the prime minister on October 7, he complained about the “manipulation of endorsements” via “corrupt money”. The president and his electoral commission also pointed fingers at the municipal councils, accusing their members intending to run for election of using their power to direct endorsements in their favor. This came in the context of the ongoing targeting of the municipal councils – the one elected authority that the president has not yet abolished. In the past weeks, numerous members and presidents of these councils have been arrested under various pretexts, in addition to unprecedented interference by the executive authority in the councils’ work.

However, some pro-Saied parties that chose to participate in the elections also accused a government minister of using his influence to facilitate the collection of endorsements for candidates close to him. These leaders opted not to name him, perhaps out of fear of criminal prosecutions like those that targeted opposition leaders for similar reasons. However, they clearly insinuated that the minister is one of the closest to Saied, holds a service-related portfolio, plays a prominent political role inside the government, and heads one of the three factions taking form among adherents of the project and Saied’s “Explanatory Campaign”, each of which has its own candidates.

On the same occasion, the president announced that he needed to revise the decree, but for reasons still unknown he has yet to do so. Although Electoral Commission President Farouk Bouaskar attributed this “accomplishment” (dissuading Saied from amending the decree) to his commission as evidence of its “independence”, statements by him and his colleagues on the commission’s board about the amendment possibility were initially modest and vague, and their stance only became clear when the gates for candidacies opened and it became certain that the president had abandoned the idea. Most probably, the need to amend the conditions that emerged in the early days of the race for endorsements subsided as time passed and most candidates of the new regime’s factions managed to gather the required number. The status of some of these candidates may also have contributed to the decision to extend the deadline for receiving candidacies hours before it elapsed.

Endorsements: A Flimsy Pillar of a Broken Project

The multiplicity of factions loyal to the president and his coup-engendering path did not ensure enough candidacies in all electoral districts. By Monday, one of the foreign districts still had no candidates, and the candidacy stage could result in uncontested victories in some districts and just one round in others because they only have two candidates. This lack of participation is due not only to the boycott by the main political forces and the poor spread of the loyalist parties and factions of the new regime in the field (all of which were unable to present candidates in all districts), but also the difficulty of supplying endorsements. In his decree, Saied had required the same number of endorsements in every district, including foreign ones, irrespective of the number of registered voters. The endorsements requirement is much harder to meet in less populated districts like Dehiba-Remada, where there are barely 11,000 registered voters and the right to run is therefore contingent on endorsement by over 3.5% of them. The issue is even more complicated in some foreign districts despite the permissibility of online endorsements. How can this condition be fulfilled in districts such as Africa, Asia, and Australia, where registered voters number only a few thousand?

All this indicates that endorsement rules, like the division of electoral districts, was not sufficiently thought out and discussed when the decree was drafted or even during the years in which the “bottom-up construction” project took shape. In the minds of the project’s architects, endorsements were a way to kill two birds with one stone.

From one angle, the idea was a response to one of the main criticisms against voting for individuals – instead of electoral lists – since 2011. The individual voting system, it was argued, privileges notable and wealthy men at the expense of women and youth, for whom guaranteeing a minimum level of representation is very difficult. Saied and his associates, who oppose the idea of gender parity in elected councils, misappropriated it into a place that renders it useless, namely endorsements. During his years of advocating the project, Saied was craftily changing the details of the conditions for endorsements to appeal to certain groups, such as unemployed university graduates, even though requiring endorsements from a particular group does not guarantee it any representation. As for the argument that Bouaskar recently made in his interview with the radio program Midi Show, namely the case of a female candidate who supplied endorsements exclusively from women, it not only fails to answer the question of women’s representation but also contradicts the electoral decree’s text. The latter explicitly stipulates that “half the endorsers shall be female and the other half male”. This is not the only fallacy to which Bouaskar has resorted since becoming a spokesman for “bottom-up construction”.

From another angle, the endorsement idea is also linked to the philosophy of binding deputyship. The MP is elected based on an explicit agreement with the constituents who nominated him or her, and who can withdraw deputyship (i.e. recall) whenever they believe the MP has strayed from it. While this philosophy in and of itself raises numerous questions from a democratic perspective, its application in the decree renders it meaningless. The decree severely constrains the recall ability with many conditions and links it not to the citizens who endorsed the MP but to a tenth of registered voters, even those who supported the MPs opponents. Even the substantive condition, namely that “the MP has breached the duty of integrity, obviously failed to fulfill his parliamentary duties, or failed to exert the necessary care to achieve the platform he presented while running”, is very difficult to evaluate. Will the electoral sub-commissions have the boldness to reject recall petitions that fulfill the formal conditions if they assess that the MP fulfilled his or her duty?

In reality, the endorsement-collecting stage exposed the breakdown of “bottom-up construction”. The second endorsement form, which the Electoral Commission developed in response to suggestions by aspiring candidates, reduces the elections to a distinctly local scope. The platform of the candidate that the endorser is asked to sign consists of a set of “projects” in the areas of “economic development” and “social development” with defined resources, timeframes, and social impact. Hence, the candidate’s promises will typically be local in nature, as though the elections are regional or municipal. In other words, the matter at hand is not national policy in areas such as taxation, social security, justice, security, and public health but promises of local investment. This vision matches the “philosophy” of bottom-up construction (if it can be considered one), which reduces the revolution to an entitlement to local development supposedly achievable by returning the say to the locals – who are unsoiled by party affiliation – and providing them “the tools”. In reality, a struggle has begun between the delegations and tribes that comprise each electoral district, with the collection of endorsements in most instances occurring based on kinship and tribalism. The decisive criterion in endorsements, as well as at the ballot box, is not the candidate’s political ideas or competence but familial ties and clientelism.

A Commission for Explaining the President’s Project

If voting for individual candidates in societies without mature political traditions and a strong and stable party system gives precedence to such considerations, then this effect will be amplified when parties are systematically excluded from the electoral process and when the main political forces boycott it. The commission saw fit to apply the concepts championed by the president, who is apprehensive about political parties, and sometimes went beyond the stipulations of his electoral decree. Bouaskar argued that banning parties from funding their candidates’ electoral campaigns is a consequence of the Electoral Law, specifically Article 77, which Saied’s decree preserved as-is, and excludes juridical persons – including parties – from the definition of “private funding”. Bouaskar thereby disregarded the fact that parties’ funding of legislative election campaigns was, under Article 76 of the same law, classified as “self-funding”, concluding from the term “lists” that this is inapplicable to the system of voting for individual candidates. He has also stated that the ballot paper will include only the candidates’ names, including those who belong to parties, even though this matter was not settled by Saied’s decree. The president of the obedient commission argued that the system of voting for individuals dictates that only the candidates’ names be included and that the deep-rooted democracies that adopt it follow the same practice. This is a blatant fallacy as the ballots in legislative elections in France, Britain, and the United States all contain the candidates’ party affiliation and – usually – the parties’ slogans. Bouaskar ignored the fact that the electoral competition in all democracies, irrespective of the ballot system, occurs among parties and not independent individuals.

The Electoral Commission, whose members were all appointed by Saied after he abolished the previous council by decree, has transformed into more than a tool for implementing the authority’s choices no matter how incompatible they are with democracy. It has become an “explanatory” commission for defending their merit: from the system of voting for individuals, to the thinly disguised exclusion of parties, to the division of electoral districts that it denied breaches the principle of equal suffrage on account of the flagrant demographic imbalance among them, to the representation of women, which will undoubtedly be very weak. Bouaskar’s alignment with the president and his explanatory campaign even prompted him to adopt the discourse of demonizing political parties and past elections that he himself helped oversee in an attempt to convince us that the 2022 elections will have the most integrity.

But the real theme of these elections is meddling. There has been constant meddling with the rules of the game (particularly the Constitution and the Electoral Law), meddling with the organization of the elections, and meddling with the composition of the commission overseeing them – all to satisfy the sultan and his concerns. This same sultan found neither the time nor capacity to mature his ideas, which he spent years advocating, before forcing them on an entire people with armored military and police vehicles and the collusion of much of the democratic transition’s elite.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] Mahdi Elleuch, Mohamed Sahbi Khalfaoui, and Sami Ben Ghazi, “‘al-Ra’is Yuridu’: Tanaqudat Nizam al-Bina’ al-Qa’idiyy wa-Makhatiruha”, Chapter 1: “Nizam Iqtira’ Malghum”.