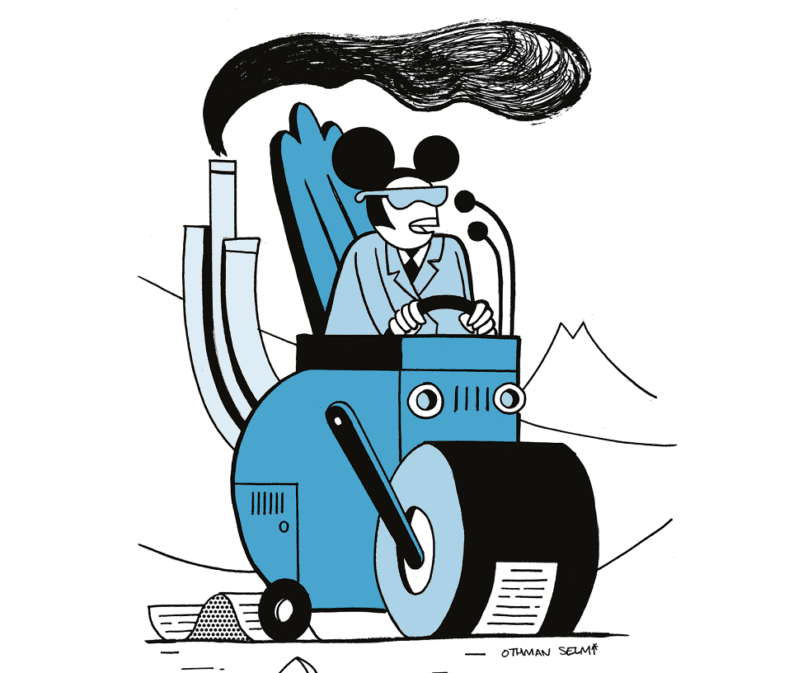

Saied Completes “Bottom-Up Construction” on the Rubble of Democracy and Decentralization

In a video recording of a Council of Ministers meeting delivered late at night on March 8, Tunisian President Kais Saied announced the dissolution of the municipal councils a few months ahead of their term’s end, along with other decrees promulgated the following day in the official gazette. Decree no. 8 changed the voting method and candidacy requirements for municipal elections. Decree no. 10 pertained to the means for electing local and regional councils and the second parliamentary chamber – the “National Assembly for Regions and Provinces” – which emanates from them. Hence, as we previously predicted, the president has pushed ahead with imposing his vision of “bottom-up construction” [al-bina’ al-qa’idiyy] without any discussion or review. These decrees coincided with his order calling the Assembly of the People’s Representatives to convene, in principle transferring legislative power to it. Hence, they reflect the president’s determination to complete his vision using personal decrees even though the Bardo assembly, which was elected by the means and terms that he wanted and that 90% of Tunisians shunned, is expected to be a mere rubber stamp for the executive authority’s bills. However, Saied’s dream of “re-constitution”, which he has unilaterally imposed thanks to the backing of the armed apparatuses and using a piecemeal and equivocal approach, can only rise on the rubble of the institutional structure that many forces have collaborated and competed to construct since the revolution. Thus, the sledgehammer reached the elected municipal councils, concluding the process of monopolizing power and demolishing all the democratic transition’s achievements, most notably the 2014 Constitution and all the institutions and authorities emanating from it.

The National Assembly for Regions and Provinces: The Contradictions of Bottom-Up Construction to the Letter

While the Assembly of the People’s Representatives was a loose translation of the philosophy of “bottom-up construction” via the adoption of the system of voting on individuals, the masked exclusion of parties, the endorsements requirement for candidacy, and the codification of representative recall, the National Assembly for Regions and Provinces is a verbatim translation of the president’s vision. This second parliamentary chamber, which Saied’s constitution stipulates participates – along with the first chamber – in approving financial laws and development plans and submitting and voting on motions to censure the government, was an opportunity for the president to realize his vision without concessions like those he was compelled to make in the decree on legislative elections.

The vision that Saied has, since at least 2013, been preaching as “new political thought” that will bring “salvation not only for Tunisia but all humanity”, is present in all its details. The regional councils are not elected directly. Instead, voters vote on individuals in each “sector” [‘imada], which is Tunisia’s smallest administrative-territorial division. The elected representatives, along with a representative for people with disabilities selected by lottery, form a local council [majlis mahalliyy] in every “delegation” [mu’tamadiyya]. The heads of the local administrations participate in this council as non-voting members. Regional councils [majalis jihawiyya] on the governorate [wilaya] level are composed of one rotating representative from each local council selected by lottery every three months. Each regional council elects a representative to the provincial council [majlis al-iqlim] and three representatives to the National Assembly for Regions and Provinces. The provincial councils – whose territorial division remains unknown – also elect a member to the national council, thereby completing the composition of the second parliamentary chamber.

Saied, the enthusiast of constitutional law history, probably derived this approach from the voting system for the Grand Council that the colonial authorities applied from 1945 to 1954 to Tunisian Muslims. Voters voted on individuals on the level of the mashyakha, which became the sector after independence. The representatives elected in each area would then meet to select their representative to the Grand Council. Despite the catchwords and mechanisms drawn from councilist thought, such as the idea of building from below and binding deputyship, “bottom-up construction” is not a Tunisian version of council democracy for two reasons. Firstly, the latter was linked to revolutionary historical contexts and dominated by the authority’s focus on means of production, with workers’ councils being the most prominent council model. Secondly, power in “bottom-up construction” belongs not to the councils but to the head of state. The system of governance, as confirmed in Saied’s constitution, is an autocratic system that undermines and marginalizes all counterpowers and places the president above any potential accountability.

This core contradiction in “bottom-up construction” between its substance and its slogan is not the only problem. Rather, every stage of this structure, as defined by Decree no. 10 of 2023, raises numerous issues and dangers. The most notable are the following.:

Firstly, voting on individuals on the sector level will increasingly weaken the political dimension of the electoral process in favor of family, tribal, and clientelist ties. What appeared in the 17 December 17-29 January 29 elections, which employed medium-sized districts, each with an average of 78,000 residents, will probably be more pronounced in much smaller districts with an average of just 6,000. Miniature districts, as many academic studies have proven, privilege political money and clientelist ties, contrary to what proponents of the vision promise.

Secondly, the decree excludes numerous groups from the right to run in local council elections. The first is Tunisians who hold a second nationality. Their exclusion violates a fundamental right guaranteed by all constitutions and charters. It discriminates against an important segment of society based, at best, on the false and unfair assumption that anyone with a second nationality cannot possibly reside in Tunisia or, at worst, the stigmatization of dual citizens as traitors unfit to represent society. From his constitution to his electoral law, Saied has insisted on excluding dual citizens despite all criticisms. To the contrary, the specific nature of local elections in democracies is supposed to open the possibility of dropping the citizenship requirement and only requiring residence in the area. Saied’s decree also excluded people younger than 23 from the right to run for local council. It also excludes people who have served within the past year as presidents or members of municipal councils, managers or personnel of municipalities, regions, governorates, or delegations, imams or preachers, and presidents of sports organizations or associations, thereby casually depriving vast groups of their political rights.

Thirdly, while the districting for the Assembly of the People’s Representatives somewhat rectified the demographic imbalance between delegations by combining some into one district and splitting others into two (although discrepancies as large as ninefold still exist), adopting current sectors as districts for local council elections raises the problem of the blatant imbalance between them. In Tunis Governorate alone, Subakha has fewer than 350 residents while Taieb Mhiri has approximately 30,000. In other words, a vote in one sector could equal 85 votes in another. The one exception that the decree stipulates to adopting sectors as electoral districts is the few dozen delegations that comprise less than five sectors, which will each be divided into five districts to ensure that the local council has at least five elected members. To be fair, the equal suffrage requirement may be moderated in a second legislative chamber in favor of a kind of equality among regions, as occurs in several democracies. However, the demographic imbalance is also an issue for the endorsements requirement, on which the president insists despite all the problems it created during the election of the first chamber. The decree’s requirement of 50 endorsements irrespective of the number of voters in the district could lead, in sectors containing no more than a few hundred voters, to the absence of any electoral competition, as occurred in the legislative elections.

Fourthly, “bottom-up construction” involves drawing lots to elevate members from the local councils to the higher councils. In his decree, the president preserved lot drawing for forming the regional councils but stipulated election as the means for elevating members to the provincial councils and National Assembly for Regions and Provinces. Inspired by ancient Athenian democracy, the lottery idea has recently attracted increasing intellectual and practical interest as one potential solution to the democratic legitimacy crisis and the tendency of representative democracy to produce what resembles an oligarchy only accessible to certain groups, such as university graduates, social notables, and professional politicians for whom political engagement becomes a career. Lottery, according to its theorists, is an alternative to election that allows true representativity based not on a choice between political offerings but on randomness. Thus, “anyone” becomes a representative of the popular will. However, the lottery in “bottom-up construction” lacks substance. The lottery takes place after the election for the purpose of selecting one sector delegate to be a regional representative, who can also run for the national assembly. In other words, it first requires running for election, which presupposes political ambition. Hence, it contradicts the idea of “rule by anyone” underpinning the lottery philosophy and reflects the appropriation of new approaches without comprehension of their meaning.

Fifthly, although the local and regional councils’ purview remains undefined, it will probably pertain to development issues within their territorial domain, with each regional council “compiling” the policies of the subordinate local councils pursuant to the “bottom-up construction” philosophy. However, the rotating membership of the regional councils will make managing matters very difficult. A three-month period does not permit members to build familiarity with subjects, and the rotation of one matter through many people will make it very difficult to deliberate and build up to decisions. As for the local councils, the decree stipulates that the heads of local administrations, if they exist, be non-voting members directly appointed by the minister. Consequently, the administration’s people may ultimately control the discussion because, unlike the elected members, they are familiar with the matters. They may also remain as permanent members, entrenching centralization contrary to the “bottom-up construction” slogan. There is a vast difference between an elected council’s right to request officials’ attendance and ask them for information or insight, and the permanent presence of officials as members representing the central political authority.

A Piecemeal and Equivocal Approach

The decree on local and regional councils and the National Assembly for Regions and Provinces is the latest episode in the process of realizing “bottom-up construction”. This process is distinguished not just by its top-down and authoritarian dimension (it is based on a coup against the Constitution and the monopolization of all power) but also by equivocation. Contrary to the moralistic image the president is eager to project, he was not clear or transparent about his intentions. Rather, he preferred to impose his vision one piece at a time. He is aware of the concerns and opposition that “bottom-up construction” provokes, but he believes that it brings salvation for Tunisia and all humanity and that he is correcting the course of history, as he wrote in his constitution’s preamble. Saied did not abolish the 2014 Constitution, which brought him to power and which he swore to respect, and at the time of his 25 July 2021 coup, he insisted that he was applying its eightieth article. He twisted the concept of a state of exception against the goal for which it was created, namely protecting the constitutional order. He then proceeded to gradually dismantle the counterpowers. He suspended the Constitution via Presidential Order no. 117, aided by law professors who, because they did not get to play the starring role in the democratic transition period, fancied they could do so in the establishment of a new republic and so ended up lending false credibility to the establishment of a nonrepublic. He launched an “online consultation” that, with its leading questions tailored to his vision, was nothing but failed democratic dressing for the coup against the Constitution. When the survey showed an inclination toward amending the 2014 Constitution instead of replacing it, he disregarded the results. He then established an “Advisory Discussion Committee” to give the impression that the constitution’s drafting would be participative, before binning its draft and delivering his own pre-prepared version. In his draft, he abolished the requirement that the Assembly of the People’s Representatives be elected directly, only to backtrack following the concerns this move provoked, claiming to be correcting errors that “leaked” into the text. He himself leaked the term “local councils” into the article governing the domain of the law – a move that the Legal Agenda interpreted as a constitutionalization of sector-level local councils distinct from the municipal councils that paves the way for the National Assembly for Regions and Provinces to be a verbatim application of “bottom-up construction”. However, throughout this entire process, Saied carefully avoided stating his intentions or putting his full vision to public debate or referendum, even though he controlled all the conditions of the 25 July 2022 referendum on the constitution.

Saied has reached the final stages of realizing his chimerical vision, relying on the state’s armed apparatuses and the state of denial that has befallen much of the elite and that he knew how to exploit. Unsurprisingly, this is coupled with an authoritarian clampdown on all opposition voices, from politicians to unionists to journalists, for he is liquidating the revolution and its gains in the name of supporting it against the democratic transition system. While he has shown an extraordinary ability to demolish everything we built over the years, his own rickety structure will necessarily be more fragile than the one he toppled and will most probably not last once he is gone. If the novice sorcerer completely disregards reality and its constraints and shows no readiness to revise his ideas or acknowledge his mistakes, then – although the cost may be high – his path can only lead to a dead end.