University Independence in Egypt: The Struggle Continues

Since the 1970s, Egyptian students and faculty members have been fighting for the independence of their universities. Starting in 1971, Egyptian constitutions have stipulated that universities are independent. Under the 1971 Constitution, university independence is guaranteed by the state and linked to the fulfillment of society’s needs and productivity. The 2012 Constitution merely stated that universities were independent without specifying the state’s role in guaranteeing that independence. The 2013 Constitution explicitly stated in Article 21 that, “The State shall guarantee the independence of universities”, without connecting it to the achievement of any particular goal. Thus, the concept of university independence has evolved according to the authors of the Egyptian constitutions. This evolution may be traced back to the development of the movement demanding university independence.

It should be pointed out that state authorities interpret the principle of university independence to mean financial and administrative independence only. Students and civil society organizations, however, take a broader view of the concept. For them, the principle of university independence means ––in addition to financial and administrative independence–– the independence of its faculty and the university council, including a guarantee of their freedom of opinion and expression. It also includes the guarantee of the enjoyment of students’ freedoms. Among the greatest threats to student freedom is the presence of Interior Ministry security forces within university walls.

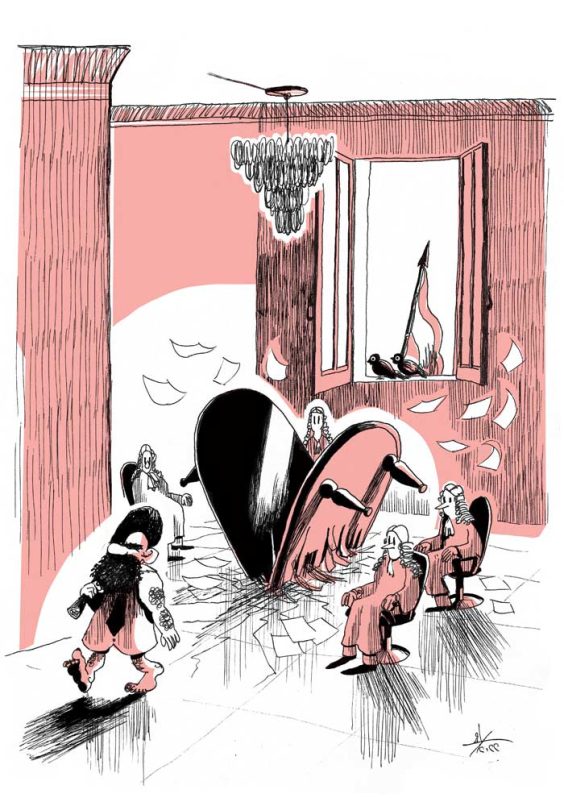

Differences in interpretations of this concept have given rise to an unending struggle between students, faculty, and civil society organizations on one hand, and state authorities on the other. The struggle over what university independence entails has centered around three main issues: the first is the students’ struggle to attain their freedoms within the university; the second is academic freedom and the independence of the faculty; and finally, the campaign to expel university guards off campus.

University Students’ Struggle to Defend Their Freedoms

Student freedoms include the existence of student bylaws that allow students to express themselves, and which address their freedom to carry out activities within the university. It also includes the freedom to hold conferences and seminars, freedom of opinion and expression on the university’s campus, and student union elections.

Demanding student bylaws that reflect the students: an all-time struggle

One of the first demands to appear in the arena of ensuring the independence of Egyptian universities related to issuing student bylaws that allow students to express themselves. These bylaws are a part of university law and address topics relating to student unions, including how they are elected and the committees that fall under the union – which in turn opens the field to various student activities. For students, the bylaws carry great importance, as they are tantamount to a constitution for the university regulating their rights and duties within the university.

The period after the July 23, 1952 revolution saw an opening-up of political activity among students, which continued until 1954. However, as authorities did not welcome political action on the part of students, they resolved to rewrite student bylaws in order to discourage such activity. This was the beginning of a permanent state of conflict between authorities and students over the student bylaws. Whenever students demanded bylaws that guarantee full freedoms, authorities sought bylaws that limit student movements out of fear that they could form an opposition force against them.

In 1976, the student movement gained a victory when it compelled President Anwar Sadat to adopt the 76 bylaws. These bylaws granted the most freedoms in the history of student bylaws, and guaranteed the independence of student elections and activities.[1] This did not last for long, however, as the bylaws issued in 1979 -with the aim of putting an end to student political activity- were among the worst that Egyptian universities have ever known.[2]

These bylaws eliminated the student union’s political committee, and required the approval of the university’s president or dean to organize any student activity. They also prevented students from freely expressing their opinion within the walls of the university, and forbade them from bringing in speakers from outside of the university to give lectures and seminars without the approval of the dean or university president.[3] In the final years of Mubarak’s rule, the student movement actively worked to demand a change in the bylaws. An amendment did appear in 2007, but without student participation. It was no different from the 79 bylaws, except for the addition of some provisions that suppressed the student movement under the threat of disciplinary action and expulsion from colleges and university compounds.[4]

After the January 25 Revolution, the pursuit of new student bylaws reemerged on the scene in force, by way of a prominent student movement. Problems arose regarding who would draft the bylaws and adopt them in the absence of an elected legislature. The limits of the Ministry of Higher Education’s role was also in doubt.

These questions were debated among the students themselves. While the Muslim Brotherhood students, who represented the majority of Egypt’s student union, were satisfied with holding workshops that included various [student] unions and the adoption of bylaws by ministry decree, this approach was rejected by independent, leftist, and liberal students, among others. The latter insisted on putting proposed bylaws to a student referendum as an expression of the independent decision making of the university and the student movement.[5]

Holding a student referendum was gaining favor. However, while referendum procedures were still underway in 2012, the Minister of Higher Education issued a decree in 2012 adopting the bylaws. This infuriated students, who considered it a threat to university independence.[6] Student anger persisted against these bylaws, and students refused to hold elections under the bylaws and up to this day continue to fight for ones that offer them a voice and are consistent with the principle of university independence.

After the revolution, the student movement expanded to private universities as well. Students at the German University demanded bylaws, emphasizing the need for students to establish the bylaws themselves. They also demanded student participation in all decisions undertaken by the university’s council. In doing so, they have expanded the concept of university independence which does not stop at the relationship between the university and the authorities, but extends to include student participation in the university’s administration.[7] Students and professors at the American University of Cairo also organized similar demands for increased student participation, and a guarantee of freedom of opinion and expression within the university. The administration responded, writing a new policy to guarantee freedom of expression for students and taking measures to guarantee student participation in decision making, and to include students on the university’s financial committee.[8]

Security interference in student union elections: a clear violation of university independence

For students, university independence also means freedom and independence when it comes to student union elections. During the Mubarak era, state authorities violated this independence by having security forces (university guards) monitor the election list and crossing out the names of members of the opposition, such as those of the Muslim Brotherhood and the Revolutionary Socialists.[9] After the revolution, students used elections as a means (among others) to pressure authorities to adopt [new] student bylaws. Students refused to hold elections as per the 1979 bylaws (amended in 2007), and likewise refused to hold elections on the basis of the 2012 bylaws, which had been adopted without student participation and decreed by executive power.

In addition, students held elections during the 2011-12 academic year according to protocol, and conducted them by themselves. They imposed these elections on the Minister of Higher Education after staging sit-ins within their universities calling for the 2012 bylaws to be struck down.[10] Thus, students achieved independence from the control of the executive authority and held the first free elections in [Egyptian] university history. However, given the ongoing conflict regarding student bylaws, the student movement has yet to attain full independence and it continues to work towards that end.

Electing University Leadership: A Cornerstone of University Independence

Article 43 of the 1972 university law stipulated that college deans should be elected as a concession by Sadat to the student movement. The latter had then reached its peak, and Sadat was trying to pacify it.[11] Law 142 of 1994, however, reversed the gains on elections, amending the article to state that college deans be appointed by university presidents – who in turn were appointed by the president of the republic.

These university laws stipulate that university leadership (its council, president, college deans, department chairs, etc.) be appointed. The president of the republic appoints the university president while chairs of department councils are appointed based on seniority.[12][13] Appointments were designated for other positions but without clear conditions. For example, the sole condition for the appointment of college deans was that they be appointed from among the professors working in the college, without the specification of other conditions. As the law allowed a university president to dismiss members of the university leadership prior to the completion of their terms, with the approval of the university board and after conducting a mandatory investigation, it provided the means to dismiss those in opposition to authority.[14]

Choosing university leaders by appointment is a clear violation of the principle of university independence. When appointments lie in the hands of executive authority, those appointments are determined according to political leanings rather than competence––and with the goal of controlling the university and banning opinions that differ from those in authority. This in turn negatively affects the level of education at the institution.[15]

Moreover, in the past, even teaching assistant appointments were subject to the approval of state security. Such oversight was not specified by law but mandated by the political regime at the time, in cooperation with the regime-appointed university presidents.[16] Authorities continue to monitor statements and opinions made by members of the faculty after they are appointed, and to remove those whose opinions stand in opposition to theirs. Examples include the investigation of a professor from Assiut University on the basis of an opinion he expressed in a lecture. The professor was dismissed following the investigation. His right to defend himself was not respected.[17]

For that reason, after the revolution, faculty and civil society organizations demanded that the university law be amended on a number of fronts; among them was the election of university administration. They held a number of marches, sit-ins, and protests on campus to demand this, and to call for the resignation of university officials – especially university presidents who had been appointed by former President Mubarak. Professors joined some of these actions.[18] This prompted some university officials to resign, while others were dismissed by their university councils.

The process of selecting university officials was changed with an amendment to the law issued in 2012, under which chairs of department councils, deans of colleges and institutes, and university presidents became elected posts. Implementing this positive development, however, ran into difficulties. The establishment of electoral procedures and standards was left to the Supreme Council of Universities, appointed by the Mubarak regime, which should serve as a warning of a lack of neutrality.[19] This has led to continued demands for the law to be amended to reflect the ideal electoral framework that would guarantee true independence to faculty members.

Unfortunately, such progress was scuttled after current President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi issued a law decreeing a return to a system of appointments. This was apparently done to assert control over the university movement that emerged after June 30 in opposition to the authorities, and which many in the media have described as a source of “chaos”.

In addition, other independence-related faculty demands remain unmet. These include autonomy in budgetary matters on a single university basis, as well as the turning of disciplinary councils into university courts guaranteeing fair representation of faculty members.[20]

University Guards: An Ongoing Struggle, Despite a Judicial Ruling

Since the days of Abdel Nasser, university guards have been used as a means to suppress the student movement. Their interference increased throughout Mubarak’s rule, especially once the guards were placed under the purview of the Interior Ministry. It is worth pointing out that the presence of Interior Ministry forces on campus is a violation of the university law. Article 317 of the law’s executive bylaws stipulates that the security unit dedicated to university security be answerable to the university president.

The Association for the Freedom of Thought and Expression, an NGO concerned with academic freedom and university independence, affirms that the presence of university guards within the university’s grounds detracts from its independence and limits the freedoms of professors, researchers, and students. The guards monitor the movements of professors, researchers, and students, and exercise control over their activities through either permitting or preventing them from taking place.[21] As noted above, these forces have removed students belonging to opposition parties or movements from election lists. They have also interfered in the organization of, and participation in, university activities such as lectures or seminars at times requiring security approval for these events; particularly if their topic of discussion is of a political or cultural nature.[22]

In 2008, the “March 9 Movement for University Independence” was founded. Among its goals is the barring of university guards within campus grounds. In addition to marches and demonstrations, they have appealed to the Administrative Courts to issue a ruling on the matter. The High Administrative Court issued a ruling on October 23, 2010 with the view that the presence of university guards within the university’s campus ran counter to the principle of university independence, as guaranteed by the Constitution.[23] This ruling was enforced after the revolution, and students and professors were able to hold a number of conferences and seminars without any monitoring. Students were also able to organize demonstrations and marches opposing decisions related to the university, or to criticize the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces at the time through seminars or by screening documentary films addressing its violations. This would have been impossible had university guards been present.[24]

However, this did not last for long; debates about the importance of the university guards’ presence resurfaced, and their return was demanded. This is particularly the case after the overthrow of former President Morsi, when authorities faced a number of demonstrations at universities. On February 24, 2014, a Summary Affairs Court issued a ruling decreeing the return of the university guards to secure the universities. Their controversial ruling raises serious questions about the court’s jurisdiction in issuing such a decision.[25] At the same time, a number of university presidents called for reintroducing guards and requested that members of administrative security be granted the right to conduct criminal investigations, which would transform them into members of the police.[26]

Consequently, a number of clashes between security forces and demonstrators occurred. On numerous occasions these led to the injury and death of a number of students. In the realm of freedom within the university, and violations of the freedoms of students belonging to opposition parties and movements, this truly marked a return to the pre-January 25 era.

Conclusion

The movement to demand university independence in Egypt is distinguished by cooperation between students and faculty members on all matters related to this goal. Just as professors have joined students in their demands for the freedom of the student movement, students have joined professors in their demands to elect university leadership. Perhaps this emerges from a particular understanding of the principle of university independence, and the desire to achieve that independence without allowing state authorities to entangle themselves in it in any way. The movement has made a number of gains at various times, and although it has not yet achieved total independence for the [Egyptian] university, it seems determined to continue until its goals are achieved.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] See: Muhammad al-Badawy’s, “The History of the Student Bylaws over 60 Years”, Yawm al-Sabaa, October 13, 2012.

[2] See: Osama Ahmed’s, “On the Drafting of New Student Bylaws”, Bawaba al-Ishtiraki, September 2, 2012.

[3] See: “Ministry of Higher Education Decrees Amendment to 1979 Student Bylaws, Known as the “State Security” Bylaws”, Al-Shorouk, March 28, 2012.

[4] Ibid.

[5] See: “Report on Recent Developments on the Issue of Student Bylaws”, Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression, October 2, 2012.

[6] See: “Anger at Universities after Education Minister Declares Student Bylaws”, Al-Shorouk, October 20, 2012.

[7] Based on a conversation between the author and a student, August 11, 2014.

[8] See: Ursula Lindsey’s, “Freedom and Reform at Egypt’s Universities”, The Carnegie Papers, September 2012.

[9] See: “The Student Movement from the Fall of Mubarak to the Overthrow of Morsi”, Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression, June 2014.

[10] See: Osama Ahmed’s, “On the Drafting of New Student Bylaws”, Bawaba al-Ishtiraki, September 2, 2012.

[11] See: Ahmad Thabit’s, “The Limits of Academic Freedom and University Independence in Egypt”, Al-Ahram, October 1, 2008.

[12] Article 25 of the university law.

[13] Article 56 of the university law.

[14] Article 43 of the university law.

[15] See: Ahmad Thabit’s, “The Limits of Academic Freedom and University Independence in Egypt”, Al-Ahram, October 1, 2008.

[16] For examples of teaching assistants that were rejected or whose appointments were suspended due to reports from state security, see Ahmad Thabit’s article referenced above.

[17] Interview conducted by the author with members of the Association for the Freedom of Thought and Expression, March 7, 2014.

[18] See: “Strikes Pervade Egyptian Universities: Students and Professors Absent”, Al-Ahram, October 3, 2011.

[19] For more, see: “Amendments to the University Law: Superficial Response to Faculty Demands Raises New Questions about University Independence and Role of the Supreme Council of Universities”, Association for the Freedom of Thought and Expression, July 19, 2012.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Press release issued by the Association for the Freedom of Thought and Expression issued April 7, 2014.

[22] See: Ahmad Thabit’s, “The Limits of Academic Freedom and University Independence in Egypt”, Al-Ahram, October 1, 2008.

[23] See: Menna Omar’s, “The University Guard between Administrative Court and Summary Affairs Court Rulings”, The Legal Agenda, February 27, 2014.

[24] See: Ursula Lindsey’s, “Freedom and Reform at Egypt’s Universities”, The Carnegie Papers, September 2012.

[25] See: Menna Omar’s, “The University Guard between Administrative Court and Summary Affairs Court Rulings”, The Legal Agenda, February 27, 2014.

[26] See: “Granting Members of the University Security Investigative Authority Threatens University Independence and the Future of Student Freedoms”, Association for the Freedom of Thought and Expression, September 10, 2013.