Systematic Torture in Lebanon: The Untold Story

On 16 December 2022, Lebanon’s Military Court held the first hearing to try crimes of torture by security forces personnel in Lebanon. This was the first application of Anti-Torture Law no. 65 of 2017, five years after its issuance. The defendants were questioned about the acts imputed to them – which caused the victim’s death – in the absence of the victim’s relatives as they have no right to be represented in the Military Court. The trial was then adjourned to 5 May 2023. In this article, we detail the indictment issued by Military Investigating Judge Najat Abu Shakra, which launched the trial, because of its importance. (Editor)

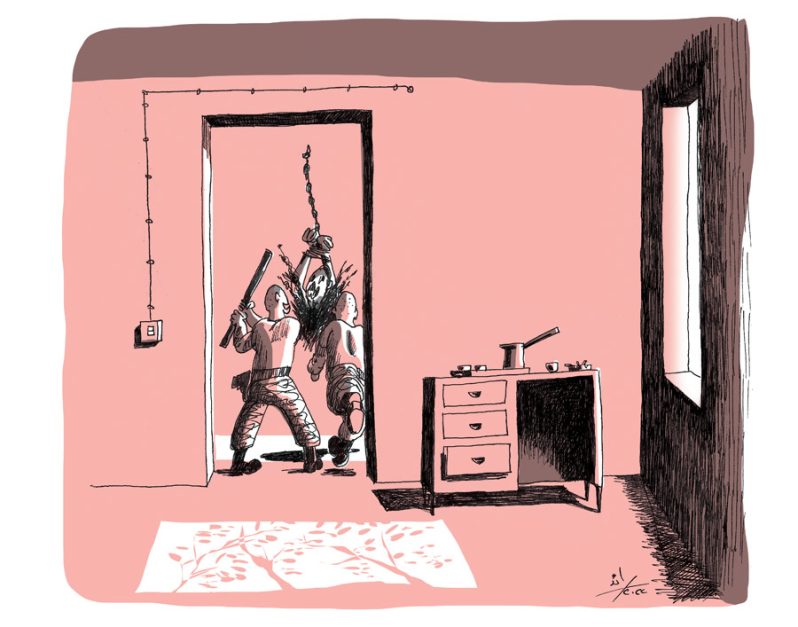

Years after Anti-Torture Law no. 65 of 2017 was issued, the public heard an unfamiliar judicial account of torture by security agencies that was more in line with those accounts that appear in statements by human rights organizations and the media. This account came in the indictment issued by Military Investigating Judge Najat Abu Shakra on 29 November 2022 in the case concerning the death of Syrian citizen Bashar Abed al-Saud during interrogation by State Security in Bint Jbeil, South Lebanon (Tebnine sStation). It was based on the investigation conducted by Acting Government Commissioner at the Military Court Fadi Akiki, which found that most detainees in the station’s jail had been tortured. While previous judicial accounts denied that torture occurred or denied its systematicity by interpreting it as an individual error usually arising out of agitation or anger provoked by the victim, this indictment thoroughly presents the facts of the torture – which was apparently a routine procedure in interrogations at that station – and ultimately charged an officer and three personnel for felony torture and a fourth with misdemeanor torture.

The investigating judge’s account of the systematic torture was based on the following evidence, which we detail below:

- Evidence that the station’s captain engaged in acts of torture.

- Evidence that station personnel participated in acts of torture to one extent or another.

- Evidence that torture had become an interrogation procedure.

- Evidence of means of torture used repeatedly on multiple victims and torture instruments unlikely to have been at the station by chance.

- Evidence that measures were taken to cover up the torture.

- Reckless disregard for the condition of tortured detainees.

Before presenting this account, we must mention that the indictment is problematic because it confirms the military judiciary’s jurisdiction over cases of torture perpetrated by security agencies in the context of investigating crimes that fall under this judiciary’s jurisdiction. Hence, the leap forward that the indictment achieves in terms of establishing and prosecuting torture coincides with a leap backward that consolidates the authority of the exceptional judiciary that has long constituted the primary avenue for marginalizing torture victims. The Military Court excludes the victims and surrounds the military and security forces with legal privileges that help them escape punishment. In this article, we shall only shed light on the account of torture found in the indictment, whereas we will address the issue of the Military Court’s jurisdiction and its negative effects in a separate article.

Evidence That the Station’s Captain Participated in Torture

The indictment showed that the station’s commanding officer played several roles in the torture. Besides his proven presence in Bashar’s torture session and, more generally, during all interrogations that occurred at the station, there is evidence that the acts of torture perpetrated there all occurred with his knowledge, in coordination with him, and – usually – at his direction. He even had no qualms about practicing torture himself. Furthermore, he played a central role in covering up the torture after Bashar died.

In fact, the statements by the personnel and testimonies by the detainees found to have been tortured stressed that the captain attended the sessions and took no measure to stop these actions, which sometimes continued for long periods. According to the personnel’s statements, Bashar was beaten, kicked, and flogged continuously for over ten minutes. When asked why he took no measure to stop Bashar’s torture, he implicitly acknowledged his inaction, arguing that “he could not yell at [the agent conducting the torture] in front of the detainee without undermining the interrogation”. He therefore merely signaled the agent to stop with his eyes, he said. He also admitted that he is always present during interrogations and that “the personnel usually use harsh treatment with detainees”, especially in serious cases, with his knowledge.

From another angle, the indictment contains facts suggesting that torture was committed at the station not just with the captain’s knowledge but also in coordination with him and at his instructions. Several detainees stated that the captain threatened to torture them if they said “yeah” [eeh] instead of “yes” [na’am]. One detainee said that when he accidentally used “yeah”, the captain ordered that he be lashed one hundred times. A detainee also reported that after jailing him, the captain “ordered those detained with him in the same case to beat him, so each one struck him once”. One detainee said that the captain was the one to interrogate him. When he gave an unsatisfactory answer, the captain would gesture to an agent to take him to another room, beat him, and teach him the statement so that he could return and recite it. Another detainee reported that the captain would reward him with cigarettes when he delivered the statement that the interrogator wanted after being tortured: “See how we treat you well once you confess?”

Moreover, the indictment included evidence that the captain himself performed acts of torture. Several detainees stated that he practices mental and verbal torture to extract confessions, beginning the interrogation with threats and allusions to torture.

The captain’s role is even worse because he took measures after Bashar’s death to cover up the fact that it occurred during torture. He tried to force the narrative that Bashar died because of a medical condition stemming from the use of a hard drug (Captagon). He stated during the investigation that Bashar had confessed to using this substance, and then he doubled down even though the urine test came back negative for 12 types of drugs, saying that “this laboratory doesn’t test for Captagon”. When the investigating judge informed him that the laboratory tested for the amphetamine in Captagon, he held firm, arguing that “it doesn’t know the ingredients of Captagon”. Moreover, under interrogation, he had no qualms about justifying the violence against Bashar on the basis that Bashar first mistreated one of the agents, which was an “insult” that warranted a “response that should be appropriate and not abusive” from the agent.

Based on this evidence, the military investigating judge concluded that the captain ordered his personnel to torture prisoners in his presence and with his consent. Hence, she indicted him for felony torture.

Evidence That Station Personnel Participated in Torture to One Extent or Another

The indictment includes evidence that all station personnel participated in torture to one extent or another, thereby confirming that the practice was normalized and treated as a tool of the trade to be used whenever necessary. The indictment revealed the prominent role played by one agent known for his temper, who beat, kicked, and flogged Bashar for several minutes before he died. However, it also highlighted other personnel’s roles, which ranged from helping him pin Bashar to the ground, cuffing his hands behind his back, and merely watching without intervening, objecting, or even leaving the torture rooms. The work – so to speak – seems to have been distributed among the personnel based on how prepared they were to torture.

In one of the testimonies showing that the personnel were collectively accustomed to practicing torture, the detainee said that although he did not know who his interrogator was because he was blindfolded, he heard several voices around him. He believes that five or six people were tossing him from wall to wall. He shouted that he was dying, but the personnel responded that they actually wanted him to die.

Finally, when the investigating judge asked the detainees to identify the faces of the personnel who tortured them, they preferred not to because they “feared that they or their families would be harassed” or they do not want “more problems with State Security”. When they delivered their testimonies, they were still jailed at the same station.

Evidence That Torture Had Become Another Investigation Procedure

The account in the indictment also reveals the transformation of torture into a potentially standard investigating procedure. The best evidence is the large number of detainees found to have been tortured at the same station. The government commissioner was able to ascertain this himself when he visited the station. It is also proven by reports from forensic doctors. Of the station’s ten detainees, seven were found to have been flogged.

The ubiquity of the torture is corroborated by the statements of the personnel. Most said that beatings or rough treatment occurred in all investigations as a routine procedure and that the severity varied based on the gravity of the crime being investigated, with no regard given to the presumption of innocence. It is also corroborated by the testimonies of the detainees, who all said that they had been tortured during interrogation. Most notably, one detainee testified that, “When he arrived at Tebnine Station, he was put in the captain’s room. The captain showed him the flogged detainees and the detainees who had not been beaten and gave him a choice between being beaten and confessing of his own volition”. Other detainees stated that they were moved to another room to be coached on what to say through coercion (torture) and that the captain rewarded them with cigarettes when they confessed after torture.

Neglecting to begin an official record when opening an investigation was also a systematic practice. While at Tebnine Station, the government commissioner seized a “header-less record”, which had been given no number, date, or start time, purporting to be about the work to arrest Bashar Abed al-Saud. The record included just a note that Bashar had experienced a medical condition stemming from his admitted drug use, as well as the details of the call to the government commissioner and the forensic doctor’s visit. Clearly, the record was only started after Bashar’s death, which shows that the interview procedures that involved kicking and beating were all off the record. This indicates that in his case and many others, torture was a preliminary procedure that occurred before the interrogation officially began, in order to guarantee a statement matching the interrogator’s preferred narrative.

Evidence That Certain Means of Torture and Instruments Specifically Designed for Torture Were Used Repeatedly

The indictment did not establish that torture instruments used at the station were seized, but the government commissioner only went there two days after the death, i.e. enough time to hide such instruments. While the personnel only mentioned the use of the wire of a mobile phone charger, medical reports and detainee testimonies indicate that instruments that could only have been at the station for the purpose of torture (cables, a lash) were also used. Some detainees also spoke about a second room to which they were taken when they delivered statements not to the interrogator’s liking and tortured. These testimonies are reminiscent of what Ziad Itani (who was detained by State Security for collaboration and later found innocent) said about being tortured in a dark room housing torture instruments at the State Security station.

Some kinds of torture and their effects also came up repeatedly in the detainees’ testimonies, thereby confirming that there is a methodology to the torture. The most significant include hanging the detainee on a door, using a whip or cable, burning, electric shocks, striking the same places (the back, extremities, and chest), flogging, kicking, punching, slapping, tossing the detainee around like a ball, giving the detainee washing powder in water to drink, forcing detainees to beat one another, blindfolding, and cuffing the detainee tightly.

Readiness to Cover Up Torture

Another matter suggesting that the torture is systematic is that the station was already prepared to deflect suspicion of torture when a detainee died. Efforts to dodge responsibility include the following:

- The attempt to manipulate the cause of death. Upon confirming that Bashar was dead, the captain took a urine sample from the body without any judicial warrant, according to the indictment. Hence, he attempted to fabricate a different cause of death, namely the use of hard drugs.

- The publication of the accusations against Bashar (involvement in counterfeiting currency and terrorism) and allusion to its seriousness, as well as the emphasis on his Syrian nationality to evoke fears and prejudices. On 2 September 2022, two days after Bashar’s death, the General Directorate of General Security issued a statement in response to the press covering the event. The statement did not address the death, its causes, or the circumstances surrounding it at all. Rather, the directorate merely published what it claimed Bashar had confessed – money counterfeiting and terrorism – as though the gravity of these two offenses in and of itself justifies torture and it therefore need not present any evidence to exculpate itself.

- The personnel’s statements attempting to portray Bashar’s torture as an individual error by one bad-tempered agent whom the victim offended. This trend is not isolated to this case. Rather, it emerges in many cases of suspected torture, as we documented – for example – in the case of torture at Roumieh Prison.

The indictment undermines all these arguments by emphasizing that all the station’s personnel participated in acts of torture and refuting other narratives about the cause of death or even the torture. Notably, the indictment explicitly cited Article 2 of the Anti-Torture Law, which stipulates that “nobody prosecuted for [torture] may offer any pretext to justify his action, such as necessity, national security imperatives, orders from above, or any other pretext”.

Reckless Disregard for Tortured Detainees’ Conditions, and Intimidation

Finally, the indictment revealed reckless disregard for tortured detainees’ conditions, their wounds and pains, and the medical attention they may critically need. Several detainees spoke about fainting, losing consciousness, and bleeding. In one of the most revealing testimonies in this regard, a detainee said that “when he passed out, he would be put in the jail and the detainees would rinse him. When he regained consciousness, the beating would continue”. Another detainee stated that “when he asked for water, he was given water containing washing powder” and that he “remained asleep for two days because of the severity of the torture”. Another said that “after he was forced to drink washing powder in water, he could barely eat or drink for ten days and had blood in his urine”. When he then consulted the officer, he was told to “bear it”.

This case revealed another form of disregard toward torture victims, one that transcends the station. Namely, a number of detainees found to have been tortured were left in jail at the same station. They were only transferred to another jail via a decision by the investigating judge two months after their torture was uncovered. This impacted the quality of the investigation as all the detainees in the investigating judges’ report asked to be excused from identifying the personnel who tortured them. This consensus reflects the climate of terror in which they were living.

Conclusion

Based on this account, the indictment referred the officer and four personnel to the Military Court for crimes of torture. However, the judge made no effort to ascertain whether a superior officer in the State Security apparatus was involved in the torture or covering it up. She did not examine the extent to which the leaders of this agency knew of the methods employed at this station or any of its other stations despite their aforementioned equivocal statements. Moreover, this agency, its leaders, and the existence of dark torture rooms in its stations have come up in other torture cases – most infamously the Ziad Itani case – that are still pending investigation.