Fabrice Riceputi: France Continues to Erase Its Crimes in Algeria

The Legal Agenda met with Fabrice Riceputi, a historian with the Institute of the History of the Present Age whose research covers French colonial history in Algeria.

Recently, he published two books: Ici on noya les Algériens, Éditions le passager clandestin (2021) and Le Pen et la torture. Alger 1957, l’histoire contre l’oubli, Éditions le passager clandestin et Médiapart (2023).

Legal Agenda (LA): In your recently published book Le Pen et la torture. Alger 1957, l’histoire contre l’oubli, you document the visit of Jean-Marie Le Pen – the founder of the National Front in France – to Algeria between December 1956 and March 1957 and his involvement in the “Battle of Algiers”, i.e. the brutal war that the French army waged to uproot the National Liberation Front (FLN). Can you give us the historical context and explain the place of torture in French colonial history?

Fabrice Riceputi: To understand the basis for accusing Le Pen of engaging in torture in Algeria, we must return to the historical context, particularly the “Battle of Algiers”, i.e. the most famous phase of the war for Algerian liberation from French colonialism, which we unfortunately know primarily through the narrative of French military personnel.

In January 1957, the socialist government at the time, with Guy Mollet as prime minister and François Mitterrand as minister of justice, decided to vest policing powers in Algiers in the French army. Officially, the decision aimed to curb the bombings that the FLN had begun carrying out against civilians in September 1956. Of course, this explanation is false and nothing more than colonial propaganda. In reality, what hastened this decision, which the extremists among the pied-noirs [Algerian-born French settlers] and many French military personnel had been demanding, was the FLN’s call for a historic eight-day general strike. In the wake of the Congress of Soummam,[1] the FLN had decided to “mobilize the urban masses” in the Algerian revolution, i.e. to engage in a new form of mass movement that was peaceful and legal, given that the French colonial law theoretically permitted those labeled “Muslims of Algeria” to go on strike. The call for a strike created a true panic among the French authorities, as documented by the French colonial archive itself. The archive contains a number of indicators that the strike would be a resounding success and thereby debunk the French propaganda portraying the FLN as a bunch of terrorists, fellagha (the name the French gave to fighters in North Africa), and bandits lacking any popular base.

Hence, the French cabinet decided to grant General Jacques Massu, the commander of the elite 10th Parachute Division, all powers in Algiers. Subsequently, approximately 10,000 paratroopers were brought to the capital. The official announcement claimed [this was done] to dismantle the Saadi Yacef-led groups behind the bombings. But the colonial archives show the reason was to uproot the nationalist movement.

However, militarizing repression for the purpose of eradicating a nationalist movement is complicated work, and the army cannot do whatever it pleases in an urban environment without witnesses. Hence, it was decided to adopt “enforced disappearance” – a method that was later employed in Argentina. In other words, the military was given the power to abduct people – usually during the night to avoid attracting attention – in accordance with instructions from Massu himself and to detain them outside the official detention sites, i.e. in villas and farms that had been seized from their owners and transformed into torture centers where abductees were interrogated on flimsy charges. Examples of these charges that I discovered while examining the French army’s archive, via records that the military personnel would fill out, are “collecting money for the FLN”, possessing “pamphlets”, and even “arrogance”, “hostility to France”, “admiration of Gamal Abdel Nasser”, and “going on strike”.

Hence, I – along with my colleague, historian Malika Rahal – deem what happened in 1957 to be a politicide, i.e. an attempt to physically liquidate all cadre and militants of the nationalist cause through assassinations, death by torture, and imprisonment in internment camps dubbed “accommodation centers” with no regard for their political affiliations (i.e. irrespective of whether they belonged to the FLN, the Scouts movement, sports teams, the Communist Party or the unions, or were religious scholars or progressive Christian Europeans). Because of the brutality of the repression, the colonial authority succeeded, in late 1957, in “neutralizing” tens of thousands of the capital’s inhabitants.

This war, which was marketed as a “war against terror” and targeted anyone linked to the nationalist movement, was waged in accordance with the “ticking [time bomb] scenario” – the same scenario that was later employed by the United States in Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib. This logic holds that when a person accused of placing explosives is arrested, torture – though barbaric – must be used to extract confessions allowing the bomb to be disarmed and civilian lives to be saved. The issue with this myth is that, to this day, nobody has been able to give an example to substantiate it. The true function of torture is to terrorize the victim’s family and whole milieu.

LA: We observe that torture and its methods were employed continuously in France’s colonial history from Indochina to Algeria, before being exported to the dictatorships of Latin America.

Riceputi: Exactly. When the scandals of the assassination of militants Ali Boumendjel[2] and then Maurice Audin[3] were exposed, their torture was explained through the legacy of Nazism in France and lingering memory of the German Occupation and Gestapo. But in reality, torture lies at the heart of the strategy of maintaining colonial “public order”. We know that from the 1930s, the French army practiced electric-shock torture widely in Indochina. Le Pen himself spent an entire year there as a reservist. We can postulate, even though we have no historical source proving it because French colonial history in Indochina is scarcely documented, that he trained in methods of interrogation and torture there.

In Indochina, the French military formulated and taught to army officers an official doctrine – the “revolutionary war doctrine” – for clamping down on a secret organization practicing armed struggle with a large popular base. After France left Algeria, this counterinsurgency doctrine would be taught in Latin America and Argentina, where the dictatorships adopted it.

LA: You talk of the French colonial archive, which is certainly an important source. At the same time, it poses many challenges to a historian. Can you give us a quick overview of this archive and access to it? Specifically, do we find traces of torture in such an archive?

Riceputi: The question is broad. When I talk about the archive, I primarily mean the Archives nationales d’outre-mer in Aix-en-Provence, which is a civil archive of the French colonial state in Algeria. In other words, it consists of the archival documents that were hastily retrieved in 1962 following the announcement that the fighting was over. Then there is the military archive in the town of Vincennes on the outskirts of Paris, and then the Archives de l’État français métropolitain in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine. Then there is the court and police archive…

Regarding access to the archive, French law theoretically allows it to be opened after 50 years, which means that the whole archive pertaining to Algeria is today open to all French and foreign nationals. But in reality, there are many exceptions – too many to fully enumerate here. There are exceptions made for protecting the personal lives of people still living or their descendants. The French government has also decided that part of the archive cannot be opened on the pretext that it still bears operational value, as in the case of the archive of France’s chemical warfare in Algeria. Researcher Christophe Lafaye – who is working on the “War of the Caves” – is suffering from this issue in particular. As we know, France employed napalm and gasses like those used in the First World War in many caves in Algeria’s mountainous regions, where National Liberation Army fighters and civilians had fled from the repression. The gasses were used to suffocate them or force them to come out. Today, Lafaye is denied access to part of this archive on the pretext that it still holds operational value.

Personally, I, along with others, advocate for the colonial archive of the war in Algeria to be completely and unconditionally opened, as is the case for the Second World War archive. The problem is that the French government is unwilling to do so. It is deliberately opening the archive gradually while establishing exceptions for the benefit of whomever it chooses.

What do we find in this archive with regard to torture and extrajudicial killing, which were legally classified – even during the war on Algeria – as criminal acts? After the war ended, the impunity of military personnel and the armed forces was codified through the adoption of a general, comprehensive, and permanent amnesty law in France. And because the actions in question were crimes, the perpetrators didn’t leave any written traces documenting them. These were secret acts that they largely succeeded in covering up because the targets were subjugated inhabitants under colonial domination with no ability to access justice. For example, in the case of Le Pen himself, there is no trace of his actions in the army archive, except for a police report.

In the course of the research that I conducted with historian Malika Rahal on enforced disappearance, many Algerian families asked us whether we had information about their relatives’ remains and burial sites, believing such information to be available in the archive. Of course, there is no trace of any of that in official documents. The colonial archive, especially that of the army, consists of lies and coverups. Therefore, it is important that we listen, in the case of Le Pen and others, to the voices and testimonies of the Algerian victims of torture and various violations, and this precisely is the approach I took in my latest book. I relied on approximately 15 testimonies of Le Pen’s direct victims that had been published by French journalists from Libération in 1984 and Le Monde in 2002. I scrutinized all these testimonies using my serious knowledge of the historical context in Algeria in that period and discerned that they are credible. Of course, Le Pen considers all this to be nothing but a conspiracy against him.

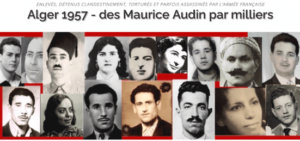

LA: You mentioned your work with historian Malika Rahal, and the two of you published a website named 1000autres in Arabic and French. Can you introduce this site to us and explain its objectives?

Riceputi: The inception of this project was my discovery in the French national archive of a record from Algiers Department, which had remarkably been preserved, containing the names of 1,500 people abducted by the French army in 1957 and 1958. Families were coming to the department to inquire about these people, explaining that the French army had smashed the doors of their homes and abducted their fathers, sons, or both, and nobody had heard anything about them since. The families would ask about where they were being held and whether they were still alive. This record in and of itself documents the brutality of the repression. Upon discovering it, I deemed that the only way to determine what happened to these abductees was to contact their families, which is what Malika Rahal and I did by launching the site. When we published the record on the site in September 2018, immediately after President Macron announced France’s responsibility for abducting and disappearing Maurice Audin, we made a public call for testimonies, in Arabic or French, from anyone who recognized names on the list of abductees and could supply us with information about their fate.

Our call was a great success, which surprised me but did not actually surprise Malika Rahal, who has a deeper knowledge of Algeria than me personally. So far, we have received hundreds and hundreds of messages of varying precision that have enabled us to corroborate more than 400 permanent disappearances out of the total 1,500. They also provided us with unique historical material because the testimonies contain rare information about the incarceration conditions and the circumstances of Algerians during this period of barbaric repression… Consequently, today we can write another history of the “Battle of Algiers”, one that takes into account the perspective of Algerians.

LA: Don’t you think that the general amnesty that the French government adopted for the torturers and perpetrators of crimes against the Algerian people immediately after signing the Evian Accords on 18 March 1962 is the main reason for France’s inability, to this day, to acknowledge its colonial past?

Riceputi: The general amnesty was announced on March 22, i.e. just four days after the Evian Accords, which put an end to the fighting. Two decrees were issued, the first pardoning Algerians who had been convicted or had warrants issued against them by the French authorities and the second pardoning all crimes and misdemeanors committed by the French regime’s forces in the course of “maintaining public security” in Algeria. Over the following years, this decree was supplemented with new additions. This amnesty law, which Charles de Gaulle adopted without even going through Parliament, was of course something that French military personnel had demanded to protect themselves from the complaints that had begun being filed against them.

This decree is not just a legal matter; rather, it is in essence a political decision and a decision concerning memory. The amnesty was primarily designed to make French society forget, and it succeeded in doing so. In that period, French public opinion was keen to turn the page on the war and reap the benefits of the Trente Glorieuses [the period of economic growth in France between 1945 and 1975]. This explains why the memory of this colonial war was lost, at least during the twenty years following Algeria’s independence. [It also explains] the great effort that was exerted to restore two central issues of remembrance, namely the massacres that the French police committed against Algerian protestors in Paris on 17 October 1961 and the torture. These two topics only returned to the fore in the late 1990s and beginning of the third millennium thanks to the struggles of the antiracism and anticolonialism movement.

This explains how Le Pen, for example, managed for approximately twenty years to file and win slander cases against anyone who reminded him of his criminal past in Algeria. General Maurice Schmitt, who is also accused of torture in Algeria and whom President François Mitterrand appointed as the Chief of Staff of the French Army, has done the same.

Of course, enforced disappearance, for example, is – as a crime against humanity – not subject to a prescription period. However, France only recognizes this principle in the case of crimes committed during the world war. The question is, why is the French Republic, even 60 years after the end of the war on Algeria, unable to acknowledge its colonial history morally and politically, not only in Algeria but also in Madagascar, Tunisia, and Cameroon? The answer lies in the fact that all the French political forces, not just the National Rally party (i.e. the French far-right), are embroiled in colonial crimes. These forces include the French Section of the Workers’ International and the Gaullist current. Here, we must recall that General De Gaulle, before belatedly agreeing to negotiate with the FLN, led the war on Algeria during the fiercest years that witnessed the largest number of Algerian civilians killed. We must also remember that a quarter of the Algerian population was, on the eve of their country’s independence, confined either in internment camps or the “regroupment camps”, into which half the rural population had been pressed.

LA: Don’t you think that the Islamophobia prevailing today among the French ruling elite, just like their complicity with the genocidal war on Gaza, is connected to their colonial heritage?

Riceputi: Yes, exactly. Personally, I always make sure to mention that for a long period, Islamophobia was emanating from the French colonial state, which labeled Algerians “Muslims”. In the very rare cases in which they embraced Christianity, they were classified in their identity papers as “Catholic Muslims”. Hence, from the perspective of the French colonial state, Muslims were a race, one subject to all kinds of prejudices and demonized across the colonial era. All these prejudices were then recycled after Algeria’s independence, especially following the first bombings to occur on French soil, and used to stigmatize French people of Maghrebi descent. To this day, and at the highest echelons of power, we are still “fighting” the abaya in schools and the burkini on beaches.

Regarding France’s stance on Gaza, we must recall that France has not witnessed any official revision of its propagandistic colonial discourse since 1962. Rather, in 2005, it officially “praised the benefits of colonialism”. The four centuries of colonial history are also taught very poorly in educational institutions. In my assessment, this ignorance of colonialism and occupation explains, to some extent, the inability of the media and political class to comprehend what is happening in Palestine as a case of settler colonialism. This precisely is what is lacking in the case of the majority of French society and its portrayal of Israel’s war on the Palestinian people in Gaza.

This Interview is an edited translation from Arabic

[1] This conference, which brought together the FLN’s historical leaders, was held from 13-20 August 1956 and enabled it to adopt a strategic organizational and political plan.

[2] Ali Boumendjel was an Algerian lawyer and militant who was killed during torture by General Aussaresses. His body was thrown from the sixth floor of the building where he was detained to give the impression that he committed suicide. Aussaresses only admitted this in 2000.

[3] Maurice Audin was a mathematics professor in the University of Algiers and a member of the Communist Party. He was arrested in 1957 and killed during torture. The French state only admitted this crime in 2018.