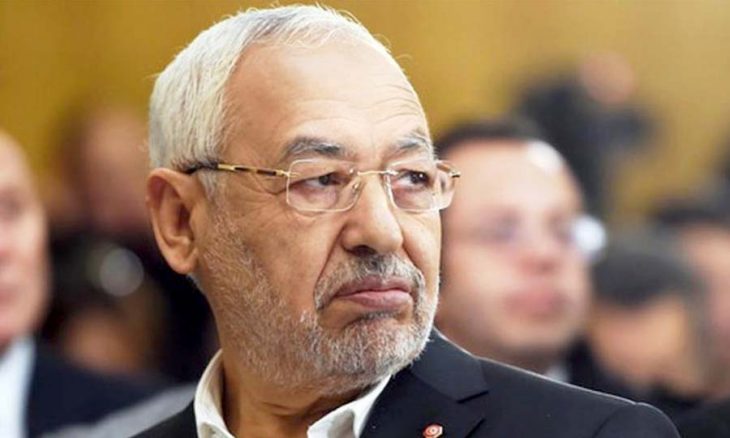

Rached Ghannouchi: Reconciliation and Forgiveness Are Integral to Truth and Redress

Transitional justice in Tunisia appears to be on the verge of important developments given the expected follow-up arising from the end of the Truth and Dignity Commission’s (TDC) work and the escalating social discord surrounding it. In this dynamic context, the Legal Agenda deemed it necessary to interview Rached Ghannouchi not only as parliament speaker but also as leader of the Ennahda Movement Party, to which the dictatorial era’s victims largely belong. The views expressed by Ghannouchi do not necessarily reflect the Legal Agenda’s beliefs and stances on transitional justice in general and in Tunisia in particular.

Legal Agenda (LA): As someone interested and having a stake in transitional justice, what’s your assessment of the outcome of the TDC’s work and the transitional justice experience that it represented?

Ghannouchi: In my assessment, the outcome of the experience is modest, to say the least. The victims did not receive redress, nor were the people accused of violations held accountable. In reality, all that was achieved was a kind of rewriting of history through listening to the victims and recognizing their right to compensation via restitution decisions that have not been implemented. Though insufficient, this work is still important. Today, the victims are passing away bearing their grief and leaving behind socially devastated children and grandchildren. Most children of prisoners were denied the right to study under normal conditions conducive to success, and some are living under materially and morally difficult conditions because of the pressure that they have so far suffered.

LA: Does this mean that the new historical narrative based on the victims’ discourse is fit to be considered truth? Some people reject this view, deeming it another one-dimensional narrative written – as always – by the victors, i.e. those who were previously victims and who therein deemed themselves all to be democrats and patriots while divesting others of these attributes.

Ghannouchi: True, this narrative was written by the victims. This is a valid complaint that does weaken the work. However, there is in any case a difference between past narratives and the new narrative. What distinguishes the new narrative is that it was written in the era of freedom and can be challenged. The TDC’s report was written by victims belonging to various political orientations. What they wrote can be debated, and anybody has the right to reject it or express a contrary opinion. Respecting the right to disagreement and pluralism wasn’t possible before, and now that has been achieved, which is good. It could be important here to note that the TDC’s work was conducted during the rule of one of the senior figures of the old regime, namely late President Beji Caid Essebsi, who opposed its work. This is evidence that it was not an authoritarian discourse so much as an expression of the victims’ opinion and the truth as they experienced it.

LA: Essebsi is not the only one accused of opposing the TDC and the transitional justice process that it carried out. You, too, are accused of having been unenthusiastic about its work and of taking stances opposed to it?

Ghannouchi: I disapproved of the approach that was adopted in the context of transitional justice. My conception was based on four things: firstly, we should be content with uncovering the truth by investigating what occurred and how it occurred so that the tragedies are not repeated. Secondly, those accused of grave violations should be called upon to apologize. Thirdly, the victims should be encouraged to forgive. Fourthly, the state should undertake to rehabilitate the victims materially and morally because it is responsible for their damages. I also believed – and still do – that the punitive approach that has so far been adopted achieves nothing but dragging the victims from one court to another. The victims haven’t benefited from that. Worse, the Specialized Chambers for Transitional Justice do not respect fair trial principles because their rulings cannot be appealed and those charged before them have been tried multiple times for the same act.

The issue should have been addressed in a better way that ultimately transcends the follow-ups now expected. The victim won’t benefit at all from the death of a policeman in prison… Transitional justice in Tunisia launched in a certain supportive political climate. Before its mandate ended, the public mood changed, so it became divorced from its context and seemed to be attempting to put the rulers on trial. For example, democratically elected president Essebsi came to be accused in this process. This raised the question, “Who is trying whom?” Had we not withdrawn from government in 2013, perhaps we would be the ones now on trial. These trials are excessive and unproductive as they haven’t uncovered the truth or provided redress for the victims.

LA: Is your objection to the “Tunisian conception” of transitional justice based on the methodology adopted for formulating its processes and therefore principled, or a political objection stemming from a lesson drawn from the effect of the change of the political and electoral mood on the public attitude toward it?

Ghannouchi: My stance has been principled since the beginning, and it was subsequently confirmed by facts that proved it correct. I have expressed this stance clearly from the outset. Here, I remind you that when the officials of the previous regime were under arrest, I received their families in my home. I also received a number of them after they were released. Vindictiveness and revenge don’t appeal to me. When I opened my home for those meetings – which were publicized – I showed my rejection of all forms of vindictiveness and grudges.

LA: Does that mean that you sympathized with those accused of violations and felt they were victims of the new regime, of which you are a part?

Ghannouchi: Regarding my feelings, I simply felt that we are passing down grudges, which does not benefit societies. True, we are victims, but we don’t want to bequeath new grudges. In reality, I opposed many measures, including the seizure law. The financial corruption cases could have been handled in another way, such as leaving the assets with their owners and charging these people with the responsibility of paying compensation for their previous mistakes. The seizure of companies and businesses that were previously producing and employing did not benefit the national community and became a big corruption issue and evidence of a failure of administration. Suffice to say, Carthage Cement – for example – had a market value of TND1.2 billion at the time of its seizure. Today, it is part of the bankrupt sector, unable to pay its personnel’s wages, and valued at no more than TND2 million. Leaving that business, among others, with its owners and imposing conditions and measures upon them to redress the damage they had caused would have been more beneficial.

LA: What’s your assessment of the state’s handling of the victims’ rights? Do you have conceptions of potential solutions for this issue, which seems to have been obstructed by – among other things – public finances, in addition of course to the lack of will and vision?

Ghannouchi: Currently, there is an ethical crisis concerning the activists [fighters] who spent their youth imprisoned, persecuted, prosecuted, and exiled and have suffered social exclusion and other injustices. After the tyranny crumbled, a sector of the Tunisian elite did not recognize their rights because of ideology and political persuasions. These influential elites denied their rights and demeaned their role in achieving and supporting the revolution. There must be a solution to this ongoing injustice, one based on recognition of the victims’ rights, morally primarily and materially where possible. The Prophet – peace be upon him – says, “You will not satisfy people with your money, but you can satisfy them with cheerful faces and good morals”. Those whom we cannot compensate financially we can honor with steps that rehabilitate them and acknowledge their sacrifices. These symbolic things could be very important to them and their families. We must accept a pluralistic Tunisia and not deny any side’s contribution to constructing it. Alienation is a dangerous idea that is like being in hell [as the Quran states]: “Every time a group enters, it curses its counterpart”. This logic must not prevail in the writing of our nation’s history. We have a duty to record the achievements of the post-independence state and its senior figures, and to credit and acknowledge the rights of the people who struggled against despotism. Were it not for them, the unjust political trials that occurred every year would continue.

LA: Speaking of political trials, what’s your assessment of the judiciary? And what’s your response to the accusation that your party – i.e. the Ennahda Movement – is interfering in it and drawing it into a revival of political trials?

Ghannouchi: Before the revolution, the judiciary’s role was limited to endorsing political cleansings. In our prisons and in exile, we saw no justice in the judiciary save for a few examples, most importantly the late Judge Mokhtar Yahyaoui. After the revolution, and in addition to the significant institutional reforms that the judiciary has witnessed, we should be mindful that the governments’ weakness prevented the potential reproduction of executive branch control over the judiciary. Hence, if the political instability had any merit, it was the consolidation of judicial independence. We are for this independence, and we reject any impingement on it. The accusations being discussed are no more than political squabbling that we must overcome. We must reconcile with and accept each other, and this can only be achieved through a critical reading of situations and history.

LA: Do you accept that such a reading should include the history of your movement? Some people accuse you, along with other opponents of the previous regime, of donning the role of victim and covering up the role you might have played in the political violence?

Ghannouchi: We are for an objective and fair reading of history that is well-founded and that breaks with the prevailing dichotomies that divide society into patriots and traitors, and democrats and Brotherhood [Ikhwanjiyya].

LA: You deem, as you previously said, that the transitional justice experience did not satisfactorily achieve the desired outcomes. Will the alternative project that it is said you will propose as an initiative – the “comprehensive reconciliation” – suffice to overcome that? What are the features of this project? If adopted, will it be a new beginning that breaks with the past?

Ghannouchi: I don’t favor the idea of a break. We must always build on what exists. We correct its mistakes, overcome its shortcomings, and build upon its positives. The work on transitional justice contains many positives and gains that we must preserve and defend, including the facts uncovered and the rights recognized for the victims. On the other hand, we think that the facts uncovered remain limited, and we need a reconciliation that ensures that the page is turned on the past. Hence, what’s needed today is comprehensive reconciliation, which – in my view – is based on three pillars: firstly, uncovering the truth; secondly, redress for the victims; and thirdly, forgiveness. Currently, legal experts and people interested in the transitional justice issue are working on elaborating these ideas and studying them. We will submit it as an initiative once it is drafted and a consensus on it has been reached. I must stress that this initiative will not, as I said, involve a break with what came before. However, it will certainly involve reform, development, and complementarity among projects in a manner that serves this just cause and ends the progress along a path leading only to acrimony.

This interview is an edited translation from Arabic.