Lebanon’s Republic of Shame: Law and Medicine as Means to Humiliate and Frighten

On January 8, 2014, at around 3pm, Lebanon’s police force, the Internal Security Forces (ISF) raided the apartment of a Lebanese citizen and arrested five people: two Lebanese, one of whom was the apartment owner, and three Syrians. All five were taken to the Moussaitbeh police station where they were detained for three days, interrogated twice and finally released.

Why was the apartment raided and everyone there arrested? What crime were they suspected of committing that warranted their detention for three days and interrogation twice, in one instance for about an hour and a half? The interrogations sought to reveal “evidence” of something profoundly intimate: the five young men’s sexual orientation and whether it departed from what traditions and most people consider to be “natural [sexual] relations”.

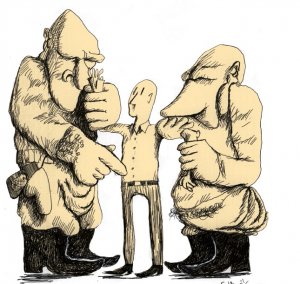

Indeed, the danger of departing from what is “natural” or “prevalent” necessitated raiding those suspected of doing so, arresting them and subjecting them to lengthy in-depth interrogations to determine the truth of their acting against “nature”. To fulfill this noble and socially necessary cause, it is acceptable to make use of all available means of interrogation even if human rights advocates regard some of those means as uncivilized and demeaning to human dignity, while the medical profession regards them as devoid of any scientific value. The threat is indeed so imminent that such means are justified regardless.

This is what happened with those five young men who were subjected to what has been termed the “tests of shame”. By examining the shape and features of the rectum, such tests aim to prove or disprove the charge of homosexuality. This article seeks to shed some light on the details of investigations into such charges, and show the appalling nature of the procedures followed. The latter indeed seem in no way consistent with the gravity of the “crime”, the evolution of social values, or even Criminal Procedure Law.

The Moussaitbeh Investigations: Let’s Ask the Maid and the Concierge

On the day of the arrest, the ISF control room received a call about a scuffle in a Beirut apartment between two young men suspected of committing “acts of sodomy inside the apartment in question”. Upon receiving this information, the ISF immediately mobilized to defend national security against the possibility that crimes of such tremendous gravity might occur.

At about 3pm, ISF officers entered the apartment, handcuffed everyone there and took them to the Moussaitbeh police station for questioning. Two of the young men arrested told The Legal Agenda that ISF officers repeatedly slapped them both while driving them to the station, and upon arrival. The investigation in Moussaitbeh focused on uncovering two fundamental issues about those five young men: the nature of their relationship (including how they met), and whether any of them had engaged in “sexual relations or any indecent acts with any of the others”.

The two young men said that the investigator at first asked them whether they wanted to call anyone. Being refugees, they asked to contact the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). However, the investigator refused, saying “why on earth would you do that?” and explaining that the right to make a phone call only applies to calling one’s family members. The police report does not mention them asking to contact the UNHCR, stating only that they did not wish to contact anyone.

Each of the five young men arrested recounted how they met, and denied engaging in indecent acts or having sexual relations with any other member of the group. Four hours after the arrest, investigators contacted the representative of the Public Prosecutor’s Office at the Appeal Court in Beirut, Judge Randa Yaqzan, to inform her of the details of the case and to proceed as per her instructions. Apparently, Yaqzan did not find the five young men’s statements convincing, and felt that there were leads to be uncovered in order to prove their crime and determine whether they were homosexuals. She therefore instructed ISF officers in Moussaitbeh to return to the Lebanese man’s home, search it and question “the maid and the concierge”, in order to gather more accurate information about their private lives.

Investigators went back to the apartment, bringing along its Lebanese owner, searched it and found nothing “apart from the furniture and some clothes”. They then questioned the place’s foreign domestic worker. The latter turned out to have arrived in Lebanon only a few days ago and did not speak good Arabic, but she was nonetheless asked about what she saw in the house, and about what happens there at night. She told them that, when she goes to sleep, “they [the owner and his friend] lock the doors and she does not see anything of what happens”.

The concierge seemed much more eager to cooperate with the Moussaitbeh investigators. Concerned for the safety of the building’s residents, the man seemed to have been keeping a watchful eye out for potential threats, such as visits from young men he found “unsettling, being so undignified (may’een) and shameless”. Yaqzan was once again consulted, and she decided to detain the five young men and submit the report to the Public Prosecution through the Judicial Police’s Morals Protection Bureau.

The Morals Protection Bureau: The Rectal Test

On January 10, 2014, two investigators from the Morals Protection Bureau arrived at the Moussaitbeh ISF station to conduct “further investigations”. They interrogated the suspects in Moussaitbeh, not at the Morals Protection Bureau itself, most likely because the latter’s detention center has become too crowded and can no longer hold any more detainees. The two young men told The Legal Agenda that they were also harassed and insulted by the Morals Protection Bureau investigators. The latter asked them questions (not documented in the police report) such as, “so who is the bride and who is the groom?”. The insults were not devoid of racism either, and they did not hesitate to tell the two youths that “you [Syrians] have polluted the country”. The young men also say that the investigators confiscated their mobile phones and went through their pictures and messages, in order to examine more closely the details of their private lives.

The Moral Protections Bureau investigators further inquired about the nature of the relationship among the detainees, including how they met and whether they “practice sodomy”. The police report claims that the five suspects were asked whether they objected to being examined by a forensic physician to “disprove the charge of sodomy”. The report states that they all agreed, one of them even expressed his “wish” to be examined by the physician. However, the two young men told The Legal Agenda a different story. They claim to have objected to the notion of being examined, but say that the investigator informed them that their objections would be used as proof that they have something to hide. As indicated in the report, Yaqzan then gave orders to “assign a forensic physician to examine the suspects”.

The story told by the two youths is in fact consistent with the text of the circular issued by former public prosecutor at the Appeal Court, Said Mirza, on July 9, 2012. Mirza’s circular states that: “public prosecutors concerned with cases of suspected homosexuality should clearly instruct the authorized physician and Judicial Police officers to carry out this procedure with the suspect’s consent, in accordance with medical regulations and in a manner that does not result in significant damage. If suspects refuse to submit to this procedure, it should be made clear to them that their refusal will be interpreted as evidence of the truth of the charge to be proven”.

However, this circular had been followed about a month later by another circular, issued by Mirza’s acting successor, Samir Hammoud. On August 11, 2012, the latter required all public prosecutors, including Randa Yaqzan, to abide by the memorandum calling for the complete cessation of any rectal tests that were issued by former Justice Minister Chakib Cortbaoui. Cortbaoui’s memo was based on the circular issued by the president of the Lebanese Order of Physicians in Beirut on August 7, 2012, which considered such tests to be devoid of any scientific value and degrading to human dignity.

As per the public prosecutor’s instructions, physician Ahmed Hussein al-Moqdad, member of the Lebanese Order of Physicians retirement fund in Beirut, arrived at the Moussaitbeh ISF station to conduct the tests. Here, the two young men say that the physician immediately began to conduct the rectal tests. He did not introduce himself, neither by name nor by profession, and did not verify that the individuals concerned had agreed to be subjected to these tests. Furthermore, they say one of the investigators would, every now and then, open the door to the room where the tests were being conducted, in clear violation of their presumed privacy.

When the physician finished conducting the tests, he allegedly did not inform the young men of his conclusions, although the five reports included in their police file indicate that the results were negative. These reports state the following: “subject matter: drawing up a medical forensic report and determining whether or not sodomy has occurred. Upon examination of Mr. […] by myself personally, there appeared to be no traces of accumulation, lesions or redness in or around the rectal area; the shape of the rectum did not appear coerced, and the rectal sphincter is functioning normally. Conclusion: there are currently no traces indicating the occurrence of sodomy”.

These conclusions did not seem to convince the public prosecution, which gave instructions to, once again, question the female domestic worker and the building concierge. Further investigation by the public prosecution reveals how grave the alleged crime appeared to them to warrant questioning the same witnesses a second time. It also suggests that the prosecution itself did not value rectal tests as evidence. The purpose of such tests is actually to frighten suspects, in hopes of obtaining a confession about a charge which is difficult to prove, and for which obtaining scientific evidence is impossible.

The migrant domestic worker was thus summoned and questioned, without a sworn translator being present. While the ISF report had indicated that the domestic worker did not speak Arabic fluently, the report of the Morals Protection Bureau mentioned that she “speaks fluent Arabic”. The MPB investigator asked her the same questions she had previously answered, in addition to a few more ‘important’ ones, such as at what time she goes to sleep.

Subsequently, the public prosecution seems to have become convinced that it would be difficult to find evidence of such a charge. It decided to conclude its investigations into the suspects’ private lives, the record of which had become tantamount to excerpts from their personal diaries. Its instructions were that “the five suspects should be released upon proof of residence and the report concluded”.

Yet it seems that the end of the story was not documented in the police report. Indeed, according to the two young men, they were asked to sign a pledge by the Morals Protection Bureau investigators. The terms of the pledge were that they would stay away from “suspicious” neighborhoods such as Ramlet el-Bayda or Raouche, never again visit the apartment of the Lebanese suspect and refrain from all contact with him. The two youths also say that the investigators told them “if we see you again, we’ll know what to do with you”.

Should the two young men’s version of events prove to be the true one, then the judicial police would have assumed new powers. It would have assumed the authority to regulate the lives of individuals residing on Lebanese soil: to choose the places they are allowed to visit and the people they are allowed to associate with – all to avoid suspicion and regardless of any evidence.

Some Concluding Remarks

The representative of the Public Prosecutor’s Office seemed extremely keen to prove the charges of homosexual relations. She had no qualms overlooking the two memoranda issued by the Lebanese Order of Physicians in Beirut, and by the Public Prosecutor of the Appeal Court, Samir Hammoud. She equally ignored all the arguments that were raised during the months of public debate in 2012, about the undignified nature of the rectal tests and the extent to which they violate a person’s privacy and dignity. She had no qualms either detaining suspects for three days, despite overcrowded jails and it being a violation of the Code of Criminal Procedure. Indeed, Article 107 of the latter bars the detainment of individuals for crimes punishable by no longer than one year in jail. Nor did she have any qualms squandering the efforts of the judicial police on investigating the suspects’ personal lives and questioning witnesses two times over. Such witnesses (the maid and the concierge) were perhaps best informed about the intimate details of the suspects’ lives, well beyond the occurrence of any specific criminal acts.

The assigned forensic physician had no qualms about violating the ethics of his profession and the memorandum issued by the Order of Physicians to which he is affiliated. He reportedly conducted yet another group test on a number of individuals, a test both medically and humanely unjustifiable under conditions inconsistent with guarantees of privacy.

The judicial police, for its part, seemed to readily breach regulations. The two witnesses report that judicial police officers beat, slapped and insulted them, and violated their privacy and forced them to sign pledges limiting their personal freedom and freedom of movement.

This case once again demonstrates the dangers of Article 534 of the Lebanese Penal Code, in view of the loopholes it provides for violations of privacy and human dignity. More importantly, it allows for overwhelming those suspected of homosexuality for one reason or another, and placing them in a position of vulnerability that can no longer be tolerated. This case yet again reveals the dire need for initiating a serious debate about the relationship between the law and the judiciary on one hand, and segments of the population that have long suffered prejudice on the other. As it seems, the latter’s rights can be violated both with ease and with impunity.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

To watch the recorded video, you can press here