Detention Orders Invoked Under Different Names in Egypt

Since June 30, 2013, Egypt has been passing through a period of many political changes. These changes gave rise to a wave of protests and sit-ins, which prompted then-interim President Adly Mansour to issue a decree in November of 2013 to regulate the right to protest. Since then, Egyptian prisons have become crowded with opponents of the current regime that hail from various backgrounds. The Ministry of Interior’s use of the term ‘security concerns’ [dawa‘i amniyya] as a tool to prevent prisoners from attending their trial hearings and detention renewal hearings, have led to extended periods of detention, particularly in cases relating to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression.

‘Security Concerns’

The term ‘security concerns’ is similar to other obscure terms that have appeared in Egyptian legislation. It is usually invoked in a letter directed by the Prisons Department to the renewal judge or the trial judge in which the department explains the difficulty of transporting the accused to attend trial. Most of these letters justify the accused’s absence on the basis that a “security-related excuse” exists. Since this term is undefined and not regulated by any legal texts, the court is left to determine its meaning. Ultimately, the court postpones the trial hearing until the accused can attend.

In a famous ruling on a case in which ‘security concerns’ were invoked to prevent prisoners from being visited, the Court of Administrative Judiciary commented on the concept’s obscurity and flexible usage. It stated:

“Invoking security reasons to prevent the detainee's relatives from visiting their family members is not legal grounds for an absolute or limited prohibition on their right to visitations, which can be carried out with controls in place to take care of the security aspect. Otherwise, the excuse, in this form, is an absolute prohibition on visitation, which is not legally permissible.”

Preventive Detention

The discussion about ‘security concerns’ raises an important question: what objective did the legislators have in mind when they stipulated preventive detention as one of the precautionary measures available? The texts that discuss preventive detention, such as article 143 of the Criminal Procedure Code, do not give a clear-cut definition of the term. This ambiguity is, of course, reflected when the code specifies the reasons and justifications for detaining the accused. However, the public prosecutor’s instruction booklet sheds light on how preventive detention is applied. Article 381 of this booklet defines it as “one investigation procedure that aims to ensure the integrity of the initial investigation, by putting the accused at the disposal of the investigator. This facilitates interviewing and interrogating the accused whenever the investigation requires it, and prevents him or her from fleeing, tampering with case evidence, influencing witnesses, or threatening victims. It also protects the accused from possible acts of revenge, and calms general feelings of agitation caused by the magnitude of the crime”.

This definition reveals the reasons and justifications for keeping an accused person in preventive detention, in the absence of which they should be released. However, what is actually occurring contrasts with this definition. In most cases of detention, the public prosecution’s investigations do not require detaining the accused for such long periods of time. If these periods are necessary, then the accused’s defense should be informed of the justifications. Furthermore, although these justifications are important, it is unacceptable for the Prisons Department to freely assert them without any checks or restrictions in place. Transferring the burden proof onto the accused by making them prove that there are no grounds for preventive detention, is also unacceptable. Having the defense continually try to refute and disprove the grounds for detention in every detention renewal hearing is illogical; the prosecution, as the side claiming that the accused may flee or influence investigation proceedings if released, should bear the burden of proving its claim.

Moreover, the continuation of detention in this manner undermines the legal safeguard upon which the lawfulness of detention is based. This safeguard is stipulated by article 54 of the Constitution, which states in its second paragraph that “The Law shall regulate the provisions, duration, and causes of temporary detention, as well as the cases in which damages are due on the state to compensate a person for such temporary detention, or for serving punishment thereafter cancelled pursuant to a final judgment reversing the judgment, by virtue of which such punishment was imposed. In all events, it is not permissible to present an accused for trial in crimes that may be punishable by imprisonment unless a lawyer is present by virtue of a power of attorney from the accused or by secondment by the court”.

The crises of preventive detention attracted increased attention after the latest amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code were made in September 2013. The amendments concerned the section of article 143 that now states the following: “In all cases, the period of preventive detention, during initial investigation and all other stages of criminal proceedings, may not exceed one third of the maximum limit of the deprivation of liberty punishment, such that it may not exceed 6 months for a misdemeanor, 18 months for a felony, or two years for a crime punishable with life imprisonment or execution.” To this text, the amendments added a final paragraph stating:

“However, the Court of Cassation and the Court of Referral, if the ruling was issued for execution or life imprisonment, may order the preventive detention of the accused for 45 days, renewable, without being constrained by the periods stipulated in the previous paragraph.”

The amended article of the Criminal Procedure Code openly contradicts the essence of the article of the Constitution mentioned earlier, despite its clarity. While the constitutional text requires the law to delimit the periods of and grounds for detention, the amendment to the Criminal Procedure Code article removed restrictions on the preventive detention period in cases where the accused is charged with a crime punishable by life imprisonment, or execution. This distinction is incomprehensible, especially so since during the investigation phase when preventive detention occurs, the accused has not yet been convicted. As a result, preventive detention resembles criminal laws that inflict punishment on accused persons, although in this case, it is more arbitrary as it is a punishment applied without trial.

When Preventive Detention is Coupled with ‘Security Concerns’

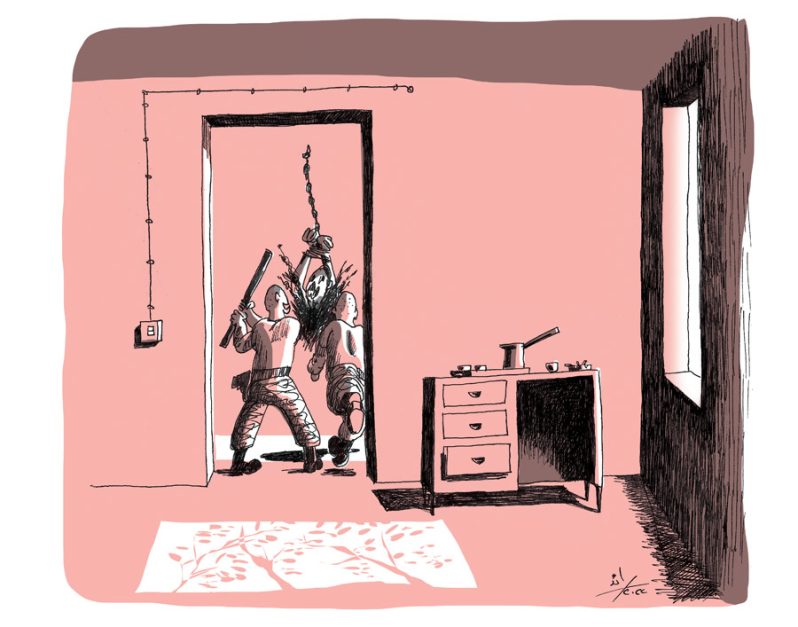

Having reviewed the critical problems precipitated by the introduction of legislation – and its application – that invokes ‘security concerns’ independently of reviewing the problems relating to preventive detention, I will now discuss the effect of the simultaneous application of both concepts. In other words, I will discuss the effect that directives preventing accused persons from attending hearings have on criminal justice, and the guarantees provided by the Criminal Procedure Code and the Constitution. By issuing these directives, the Ministry of Interior, via its Prisons Department, has taken over the role of the Public Prosecution and the renewal judge. The hearings for renewing detention specified by the legislators for the purpose of completing investigation procedures, and issuing a decision about the benefit of prolonging the accused’s detention have become superfluous, routine procedures that bestow legitimacy on the ministry’s transgressions in detaining accused persons. Hence, the legal measure [of preventive detention] has become an unlawful act that, in its effects, very closely resembles detention orders.

The consequence of invoking the accused’s absence from trial sessions under the guise of security concerns, as well as the lax rules of preventive detention, is that accused persons are detained without legal basis or specific charges. This facilitates interference by political forces and personal whims. It also conflicts with the Constitution’s texts and the international agreements that Egypt has signed, particularly those relating to the principles of a fair and equitable trial. Among the most important of these principles is the right of accused persons to defend themselves in person, or by proxy, as stipulated by article 98 of the Constitution:

“The right of defense either in person or by proxy is guaranteed. The independence of the legal profession and the protection of its rights is a guarantee for the right of defense. The law shall provide all means by which those who are financially unable can resort to justice and defend their rights.”

This stipulation is consistent with the purpose for which preventive detention was legislated. It stands to reason that it enables accused persons to defend themselves from allegations during the investigation process, but this is not occurring due to their absence from hearings. This matter also concerns the right to have detention reviewed. Every person, after being arrested and detained, has a right to promptly appear before judges so that their detention order may be judicially reviewed. This right, known in some countries as ‘the right to attend’, is explicitly stipulated by paragraphs 3 and 4 of article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The aim of such a procedure is to examine whether there were legal justifications for arresting the accused, and whether detaining them before trial is necessary.

A Legal Case to Delimit the Concept of ‘Security Concerns’

In the face of these legislative loopholes which allow for trial proceedings to be obstructed, and for the Constitution’s texts to be rendered inert, it is now necessary to make legislative reforms to plug them. However, the absence of the Egyptian parliament has made reforming the Criminal Procedure Code difficult. This prompted the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE) to open case no. 44498 of year 2015, whose first hearing before the Court of Administrative Judiciary is set to occur on June 2. In this case, filed against the president, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Interior, and the Public Prosecution, the AFTE is calling upon the courts to compel the Ministry of Interior to define the meaning of ‘security concerns’, and thereby limit the cases in which the administrative authority can be prevented from bringing accused persons from their places of detention to attend trial hearings, or detention renewal hearings. The case also calls for defining the criteria for assessing the degree of security risk that transporting accused persons to such hearings represents. The case is based on the negative effect that decisions preventing accused persons from attending hearings has on the criminal justice system, and the role that the Criminal Procedure Code plays in realizing criminal justice based on a balance between rights, freedoms, and public interest.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.