Bloody Legal Lessons from Gaza I: Israel’s Actions Are Not Self-Defense

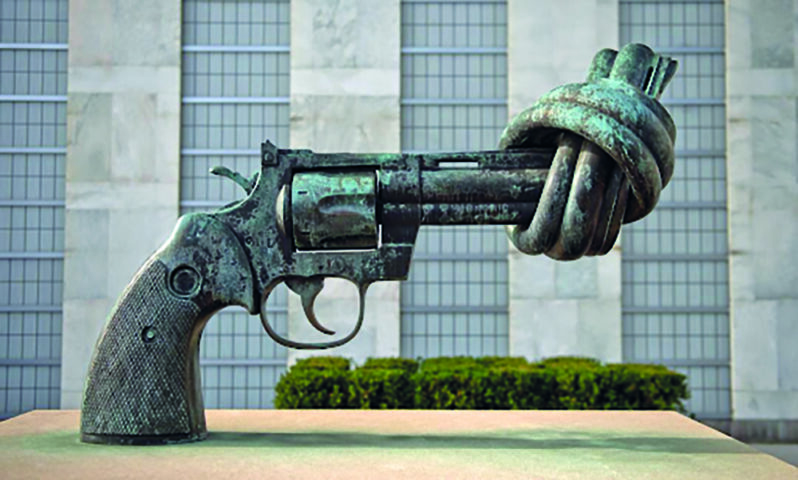

International law – especially insofar as it pertains to the use of arms, the prevention of wars, collective security policies, and the controls imposed during wars or armed conflicts – is said to be a sublime step that humankind took following the tragedies and brutality of the two world wars, a step toward presumably humanizing humanity. Tell this to the children who have lost their mothers, sisters, homes, limbs, or lives during the past week. To them, the self-evident reality is that this step does not provide them with any protection. Rather, it seems like a sly allusion to the presence of protection that does not really exist, or a fig leaf behind which the major powers dominating the “international community” hide while they punish whomever they please and back whomever they please.

Today, what has been clear to the Palestinian people for decades is plainly evident to everyone: occupation is illegal, yet a reality. Killing civilians is a war crime, yet a reality. Self-determination (in any way possible) is a legitimate right, yet criminalized.

Is our goal to implore the international community to comply with the international law it established? We are not that naive. Day by day, the fact that international law does not deter violence or its brutality becomes more evident. International law’s greatest effect is that when a country chooses to launch a war, it is compelled to recruit a group of legal experts to interpret the legal rules in a manner consistent with its actions. The notion that the decision to attack and launch a war can be deterred by a legal text or custom is untrue. Moreover, the most important recruitment that occurs during wartime seems to be directed not at legal experts but at the media, to which enormous financial and human resources are allocated in order to push a brutal narrative that has no room for international law. The stances of Western states that claim to respect the law, and occasionally even to enforce it, only confirm that this law was established to tame us, i.e. to tame the weak. Why, then, do we make an argument based on international law now? Our goal is to expose the international community and hold a mirror up to it, a mirror showing the shredded remains of children, women, and men, along with its professed standards that are debunked by reality.

In this series of articles, we will review the various dimensions of Israel’s breach of international law. We will begin by questioning its “right to self-defense” in order to refute that its use of violence is legitimate (part 1). Then we will elaborate on and establish the numerous violations of international humanitarian law, war crimes, and crimes against humanity that it is committing (part 2), crimes that go beyond these criminal definitions to reach the point of genocide (part 3). Finally, we will present Palestine’s history with the International Criminal Court (ICC) as a potential means of holding Israeli officials legally accountable (part 4).

Before doing so, we must recall the distinction adopted between the law prohibiting and deterring war (jus ad bellum, jus contra bellum) and the law of war (jus in bello), also called “international humanitarian law”. The former defines the conditions under which arms and violence may be used in international relations and stems primarily from the United Nations’ (UN) Charter, the interpretations and decisions of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and the international practices that develop the interpretation of these rules. The latter establishes legal controls that apply during the use of violence and includes the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols. Adjacent to these two fields developed the concept of international criminal law (primarily the ICC’s Rome Statute), which is an attempt to “legally” punish criminal acts of war. Since its creation, Israel has violated virtually all these rules.

This Aggression is Not Self Defense

In response to Operation al-Aqsa Flood, Israel – as usual – considered itself to be in a state of legitimate self-defense and quickly received the steadfast and unconditional support of its key ally, the United States of America (USA), as well as the support of some European states,[1] which declared that they “stand with Israel”. The Zionist state, since its inception, justifies all its acts of war (and other acts) on this basis. Even the occupation,[2] the construction of settlements, and the construction of the separation wall[3] all occur under the pretext of self-defense.

However, a close examination of Israel’s actions promptly shows that what it calls a right to self-defense is not so, and its invocation of self-defense conflicts with the definition and requirements that appear in Article 51 of the UN Charter. Moreover, this right falls under the rules of international relations, not the framework that applies to an occupying state’s relationship with the people under its control.

Occupation Does Not Have the Right to Self-Defense, but the Occupied Has the Right to Resist

Any approach that grants an occupying country the right to self-defense clashes with the right to self-determination, which is one of the UN’s goals. Otherwise, the right of defense would totally cancel out the right to resist, which might be the primary tool for ending the occupation.

Article 1 of the UN Charter states, “The Purposes of the United Nations are… To develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples”. Article 55 reemphasizes this principle. The inclusion of this phrasing, which was an initial attempt to supply colonized peoples with legal tools to demand independence, reflects the anti-colonial, liberationist climate at the time of the Charter’s adoption. While the Charter did not define the scope of this right, it was clarified by a succession of UN General Assembly resolutions. Article 1 of Resolution no. 1514 of 1960 established the foundations of the right, stipulating that, “The subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation constitutes a denial of fundamental human rights, is contrary to the Charter of the United Nations and is an impediment to the promotion of world peace and co-operation”. Then came Resolution no. 2625 of 1970, which declared the official principles of international law concerning friendly relations and cooperation among states. The fifth principle stipulated “equality among peoples in their rights and their right to self-determination” and charged every state with a “duty to refrain from any forcible action which deprives peoples… of their right to self-determination and freedom and independence”. It also gave such peoples, “in their actions against, and resistance to, such forcible action in pursuit of the exercise of their right to self-determination”, the right “to seek and receive support in accordance with the purposes and principles of the Charter”.

The clearest resolution, however, is Resolution no. 3246 of 1974. The resolution “reaffirmed”, in Article 3, “the legitimacy of the peoples’ struggle for liberation from colonial and foreign domination and alien subjugation by all available means, including armed struggle”.

During the negotiations concerning the adoption of these resolutions, the socialist and “unaligned” states demanded an explicit recognition of the right of colonized peoples to “self-defense”, but the Western states refused it, fearing other countries would become involved in peoples’ liberation struggles via recourse to the right of collective self-defense. Hence, colonial states’ relationship with the peoples under their control came to be governed by rules different from the UN Charter’s rules on the legitimate use of violence (jus ad bellum). The best evidence of this is the preamble of Resolution no. 3314 of 1974, which reaffirms states’ duty “not to use armed force to deprive peoples of their right to self-determination, freedom and independence”.

Even international humanitarian law has developed in this direction. The first Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, adopted in 1977, expanded the conventions’ application to include peoples fighting against colonialism, foreign occupation, and racist regimes in the exercise of their right to self-determination, thereby adding a new case on top of the cases of armed international conflicts (between two states) and non-international armed conflicts (civil wars) already covered. For the purposes of international humanitarian law, these wars of liberation were considered to fall under “international armed conflicts”, even though they may not actually be between two states.

Hence, modern international law distinguishes between the relationship linking equal states and the relationship linking an occupying state to the people under its control. In the first context, the law obligates states to refrain from using violence in their international relations, based on the UN Charter, except for self-defense. As for the second context, i.e. a colonizing/occupying state’s relationship with the people under its control, it is governed by the principle of the right to self-determination, and the colonizing state does not have the right to self-defense. The conclusion that arises from this is that the prohibition of violence in international relations is reciprocal, but in the context of peoples’ right to self-determination, this prohibition is restricted to the foreign and colonial state and does not apply to the people exercising their right to self-determination.

Although these facts are clear, the Israeli entity continues to twist international law and muddle its concepts, especially by forcing normalization of its constant wars and violent practices against the Palestinian people and seeking recognition of their legitimacy, which it has so far failed to achieve even though its efforts have been systematically facilitated by the USA and several countries of the Global North. The latest testament to this came on October 18 in the form of the US veto to a draft resolution imposing a temporary truce to deliver essential humanitarian aid to 2 million Gazans. Explaining the veto, United States Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield said that “this resolution made no mention of Israel’s right of self-defense… Israel has the inherent right of self-defense, as reflected in Article 51 of the UN Charter”. The reality is that the USA is virtually the only state to clearly and consistently support Israel’s right to self-defense every time it attacks the occupied territories. Other countries, on the other hand, often express rejection of this right, even if its invocation in the political discourse in several European countries has recently increased.

Self-Defense Does Not Justify Preemptive Wars, and Stopping Hamas’ Offensive Does Not Justify a War to Eradicate the Movement

In its systematic appeal to the right to self-defense, Israel often invokes this right pre-emptively. In other words, it invokes what could be called a right to “legitimate preventative defense” to justify military action aimed not at stopping an offensive launched against it but at precluding the possibility of such an offensive. Here, too, Israel’s arguments have met with constant opposition from the international community as a whole, with a virtual consensus emerging that an aggression allows recourse to self-defense only to repel it, not to repel a potential aggression later.[4]

Of course, Israel deems Operation al-Aqsa Flood an aggression against it. On 7 October 2023, it faced a wide-scale rocket attack and a ground incursion by Hamas fighters, who took control of several settlements and military positions, captured 200-250 Israelis, and took them back into the Gaza Strip. The number killed on the Israeli side climbed to 1,400. On October 8, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu delivered a speech announcing that Israel is at war. In it, he said:

“The Hamas Movement has begun a barbaric and evil war… The IDF will immediately use all its power to destroy Hamas’ capabilities. We will eliminate them and take mighty vengeance for this black day that it imposed on Israel and its citizens…. All of the places where Hamas is deployed, hiding and operating, in that wicked city, we will turn into rubble … At this hour, the IDF is clearing the terrorists out of the last communities [settlements]. They are going community by community, house by house, and restoring our control… This war will take time”.

Netanyahu’s speech clearly shows that the goal of the war is not only to repel an offensive underway and reestablish control over the settlements. This is confirmed by the fact that the war on Gaza continues even though the Israeli forces announced, on October 9, that they had retaken all the settlements. It is also confirmed by statements by various Israeli political and military officials explaining that the goal of the war is to eliminate Hamas and thereby avert any subsequent offensive.

As for the argument that the war is being continued for the goal of freeing the prisoners (a result of the “aggression” itself), it too is weak. Israel previously used the self-defense argument to intervene in Uganda in 1976 and free Israelis captured in an aircraft hijacking,[5] but the African states opposed the Israeli stance and deemed that Israel had violated Ugandan territorial sovereignty. Hence, there is no clear principle in international law that allows recourse to self-defense to protect citizens or free prisoners. On the de facto level, Israel is clearly prioritizing the elimination of Hamas over freeing its prisoners. As of October 16, the Israeli bombing had killed 22 of these prisoners, according to a statement by Hamas’ armed wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades. Moreover, the Israeli army’s radio Galei Tzahal announced an “Israeli decision” that attacks on Gaza would be carried out even at the cost of harming the Israeli prisoners, unless accurate information about their location is available.[67]

Invoking a Fight Against Terrorism Does Not Justify War

International law is supposed to set the rules for relations among states. The rules governing armed clashes and peacekeeping are exclusive to states. It follows that the right of self-defense is a legitimate right of states alone. However, it also follows that this right is exercised exclusively against states, as has been established by international legal texts. UN General Assembly Resolution no. 3314 of 1974 defines aggression as “the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, territorial integrity or political independence of another State”. This is the stance of the ICJ, which has repeatedly affirmed that self-defense can only be invoked to repel an aggression by another state conducted directly[7] or by irregular forces established to be under the command of that state and acting as part of its military.[8]

After the events of 11 September 2001, terrorism entered the battleground of international law regulating violent conflicts with the coining of the term “war on terror”. However, terrorism – despite modern attempts to expand and include the concept – has traditionally fallen outside the inter-state framework. It traditionally constituted a separate subject handled through infra-state cooperation among states on the basis that “terrorists” are individuals not equivalent to states, i.e. through international agreements to avert and punish it through “policing” and judicial – not military – anti-terrorism agreements.

In other words, to this day, there is no definition of terrorism in international law, even though it was used to justify the enormous, bloody actions that the US launched in Afghanistan. To justify their war, and even though they deemed the attack to have been perpetrated by al-Qaeda, the US tried to attribute responsibility to the Taliban government by accusing it of allowing the organization to prepare for the attack from within its territory. They thereby attempted to broaden the concept of self-defense in two ways: incorporating aggression by a non-state organization into its conditions, and indirectly charging the state with responsibility.

As the concept of terrorism has been used, especially by Israel, as a political pretext to broadly deny occupied peoples the resistance label and – by extension – the right to resist, we find ourselves facing more of a battle of “classifications” than a legal battle. Therefore, Israel’s claim that it is waging a war on terrorism is not, essentially, a legal one. In the UN General Assembly in 2018, several countries rejected the expansion of the concept of self-defense to include “war on terror”[9] and the twisting of collective security mechanisms to confront terrorism. One feature of international law is that its rules cannot be changed with only the agreement of the militarily (or economically, in other cases) powerful states. Rather, changes require the agreement of all states. Moreover, while France had rejected the expansion of the concept of self-defense to include responding to terrorism prior to 2015,[10] its authorities’ use of the anti-terrorism argument following the events of 13 November 2015, when Paris suffered bloody attacks targeting cafes, the Bataclan theater, and the Stade de France, was widely criticized by French academics.[11]

This legal consistency is also clearly evident from the ICJ’s stance in 2004 (i.e. after the events of 9/11). That year, in a case pertaining directly to the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories, the court – while practicing its advisory role – reaffirmed that Article 51 of the Charter recognizes “the existence of an inherent right of self-defense in the case of armed attack by one State against another State”.[12] In other words, the court deemed that the right of self-defense applies exclusively “ in the case of armed attack by one State against another State.”. Note that the court, to deem a state to have committed an aggressive act, applies the customary norms pertaining to a state’s responsibility for an illegal international action provided that the state’s effective control over the irregular armed groups has been established.

No State May Adopt Means of Reprisal or Private Justice

In the Security Council’s early years, the discussions therein stressed self-defense as a legitimate and fundamental right. Later, the discussions turned toward the details of its conditions, establishing that armed attack, proportionality, and necessity are the elements that distinguish permissible defensive action (deterrent action) from reprisal (punitive action banned under the UN Charter). UN General Secretary Dag Hammarskjöld stated clearly that “self-defense does not permit acts of retaliation, which repeatedly have been condemned by the Security Council”.[13] This was explicitly stated in the aforementioned Resolution no. 2625 of 1970, which explained that pursuant to its first principle (i.e. that states refrain in their international relations from threatening or using force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state or in any other manner that conflicts with the purposes of the UN), states have a “duty to refrain from acts of reprisal involving the use of force”.

In modern international law, “punitive authority” is reserved for the Security Council. No state may punish whoever attacks it; rather, the right of self-defense only allows it to temporarily take physical action to repel the aggression until the Security Council takes action. This is affirmed by Article 2 of the Charter itself: “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations”. Hence, the cases in which recourse to armed force is permitted (self-defense, military intervention with the state’s approval, or military intervention with the Security Council’s approval) are all exceptions to the rule, namely nonviolence in international relations. Exceptions are interpreted restrictively, not expansively, and no state is allowed to enforce its own private justice, whether in the form of punishment or reprisal. Note also that even in the case of a state exercising self-defense, Article 51 of the Charter requires it to inform the Security Council, which has the right to take, at any time, whatever actions it deems necessary to preserve or restore peace and international security. In other words, self-defense (assuming its conditions are met, which is not the case here) remains a temporary measure permitted until the Security Council promptly intervenes in accordance with Section 7 and may under no circumstances transform into private justice.

Disproportionate War

Another condition for exercising the right to self-defense has been transgressed, namely the requirement to abide by the principles of necessity and proportionality, which are inherent to the exercise of this right. This is what prompted the ICJ to hold that “the submission of the exercise of the right of self-defense to the conditions of necessity and proportionality is a rule of customary international law’[14], meaning that the right of self-defense only justifies measures that are proportionate to the armed attack and necessary to respond to it. States even often use their compliance with the principles of necessity and proportionality as evidence of the legitimacy of their action.[15]

These two principles also appear (in more detail) in the Geneva Conventions (international humanitarian law), and violation of them constitutes other kinds of crimes (war crimes, crimes against humanity) and has consequences in this framework that we will detail later. This distinction between rules sometimes prompts states, after wars end, to acknowledge that they violated proportionality and necessity in practice while arguing that they only did so in the context of exercising their legitimate right. However, this stance is condemnable. As the ICJ stated in its advisory opinion on the legitimacy of using nuclear weapons (1996), self-defense must respect the rules of proportionality and necessity to remain classified as legitimate action.[16]

So what do proportionality and necessity mean in the case of aggression? Since self-defense means neither reprisal nor punishment, as previously explained, the ICJ’s phrase “measures proportionate to the aggression” must be understood in a precise and balanced manner. The measures taken in response to the aggression should be proportional to not the aggression itself, but – specifically – to what is necessary to stop it.[17] The attacked side cannot argue that defending itself means “completely eliminating” the attacking side, as with this justification it is responding not only to the attack that occurred but protecting itself preemptively from any subsequent attack, as previously explained. This is totally rejected by international law.[18] Likewise, the attacked side cannot use means of war that go far beyond, in terms of their human cost, the “legitimate” military objective. This principle of proportionality is also extensively detailed by international humanitarian law, which applies it by imposing restrictions on the choice of means and methods of war. Clearly, the number of casualties and the destruction left by Israel’s war on Gaza (and repression and violence in the West Bank) in and of itself indicates the disproportionate nature of the Israeli operation, which is also confirmed by many statements by the Israeli prime minister and other government officials. To demonstrate this, we need only refer to the figures published on October 20 by Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor – figures that are inflating every day.

The Israeli entity is violating the principle of proportionality and most rules of international humanitarian law through a collective punishment that involves completely blockading the Gaza Strip, preventing access to electricity, water, and medicine, failing to differentiate between civilians and military by targeting residential areas, hospitals, schools, and places of worship, and using banned weapons. Therefore, its actions can only be classified as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and even genocide given that they are coupled with clear intent to conduct ethnic cleansing. This we will elaborate on in another article.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] On October 9, France, Germany, Italy, and Britain issued a joint statement with the USA expressing “steadfast and united support to the State of Israel… in its efforts to defend itself”. On October 15, the European Union states collectively issued, via the union’s council, a statement “strongly emphasiz[ing] Israel’s right to defend itself”, albeit “in line with humanitarian and international law”.

[2] In 1967, the Israeli representative justified the operation to occupy the territories as self-defense against an attack by the United Arab Republic. La déclaration de M. Eban, in Nations Unies, Conseil de sécurité, documents officiels, 1348 ème séance, 6 juin 1967, p.15, § 144, 145 et p. 16, §148, 153 et 155.

[3] See the Israeli government’s written submission to the ICJ in the case of the Advisory Opinion Concerning the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (2004).

[4] Olivier Corten, “Le droit contre la guerre”, Pedone, 2014, p. 663-716.

[5] Doc. off. CS NU, 31e année, 1939e séance, Doc. NU S/PV.1939 (1976) para. 115.

[6] This practice, also known as the “Hannibal Protocol”, gives priority to “destroying” Hamas even if doing so endangers the lives of prisoners. However, no official or public decision to apply this protocol in the current offensive has been issued.

[7] ICJ decision in the Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America), 1986, p. 103, paragraph 195:

“The Court sees no reason to deny that, in customary law, the prohibition of armed attacks may apply to the sending by a State of armed bands to the territory of another State, if such an operation, because of its scale and effects, would have been classified as an armed attack rather than as a mere frontier incident had it been carried out by regular armed forces.”.

[8] ICJ decision on the Case of Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda), 2005, p. 168, paragraphs 146 and 147. Note also that while Uganda claimed that its actions fall within the framework of self-defense, it absolutely did not claim that the acts of aggression that targeted it were conducted by the armed forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Rather, the “armed attack” cited was conducted by the democratic resistance for Congo group. In paragraphs 131-135, the court stated that in the absence of sufficient evidence of the direct or indirect involvement of the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in these attacks, the attacks emanating from armed bands or irregular forces cannot be considered attacks by, or on behalf of, the Democratic Republic of the Congo under Article 3 G of General Assembly Resolution no. 3314 (XXIX) on the Definition of Aggression. Based on the evidence available to it, the court deemed that the Democratic Republic of the Congo cannot be held responsible for the recurrent and condemnable attacks. As it stated in paragraph 147 : “For all these reasons, the Court finds that the legal and factual circumstances for the exercise of a right of self-defence by Uganda against the DRC were not present.”

[9] See Mexico, Statement to the United Nations General Assembly Sixth Committee, 73rd Session, Agenda item 85: Report of the Special Committee on the Charter of the United Nations and on the Strengthening of the Role of the Organization (12 October 2018); Brazil, Statement to the United Nations General Assembly Sixth Committee, 73rd Session, Agenda Item 111: Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism (3-4 October 2018); and UNSC Verbatim Record, UN Doc S/PV.8262 (17 May 2018) 44-5.

[10] Déclaration de J.D. Levitte, représentant permanent de la France aux Nations-Unies: « Nous avons estimé, à l’unanimité, que 6000 personnes tuées-chiffre avance le 12 septembre – par des avions civils devenus des missiles n’est plus un acte de terrorisme mais une véritable agression armée. » La résolution en conséquence, reconnaît le droit « à la légitime défense individuelle et collective. » (Le Monde 18/11/2001). La France a donc mis l’accent sur le fait que ces attaques terroristes étaient massives et d’une exceptionnelle gravité, du fait qu’elles causèrent des milliers de victimes et eurent comme cibles des bâtiments civils dans le territoire d’un État souverain.

[11] Franck Latty, “Le brouillage des repères du jus contra bellum. A propos de l’usage de la force par la France contre Daech”, Revue générale de droit international public, 2016/1, p. 11-39.

[12] ICJ, Advisory Opinion Concerning the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, 2004 volume, p. 194, paragraph 139.

[13] S/3596, Doc. off., 11e année, Supplément d’avr.-juin 1956, paragraphe 46.

[14] ICJ, Advisory Opinion Concerning the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, Reports 1996, p. 245 paragraph 41[15] One example is the 13 April 2018 tripartite American, British, and French strike targeting a research site and two centers for producing and storing chemical weapons in Syria. According to the French representative in the Security Council, “Finally, our response was conceived within a proportionate framework, with precise objectives. The main research centre of the chemical weapons programme and two major production sites were hit. Through those objectives, Syria’s capacity to develop, perfect and produce chemical weapons has been put out of commission. That was the only objective, and it has been achieved” (UN doc. S/PV.8233, p. 9). The American representative made the same argument: “The targets we selected were at the heart of the Syrian regime’s illegal chemical-weapon programme. The strikes were carefully planned to minimize civilian casualties. The responses were justified, legitimate and proportionate” (Ibid., p 5).

[16] Judith Gardam, citing Christopher Greenwood, “Jus ad bellum and Jus in bello in the Nuclear Weapons Advisory Opinion” in L. Boisson de Chazournes and P. Sands (eds.), International Law, the International Court of Justice and Nuclear Weapons, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 247-258.

[17] Dissenting Opinion of Judge Higgins, “Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons”, ICJ Report 1996, p.583-584.

[18] Judith Gardam, “Necessity, Proportionality and the Use of Force by States”, CSICL, 2004, p. 165.