Yemen’s Partnership Agreement: Towards Ending Judicial Quota Appointments?

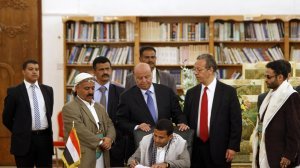

On September 21, 2014, the Peace and National Partnership Agreement was ratified in Yemen. Comprised of 17 articles, it aims to resolve the crisis between the Houthis (Ansar Allah), the central government and the country’s various political factions. Article 6 states that the president “shall exercise his constitutional [authority] to ensure fair representation of all constituencies in executive bodies”. It adds that, “fair participation in judicial bodies shall be ensured [in accordance with the outcome] of the National Dialogue Conference”.

This agreement has introduced a new political reality and turned the tables on everyone. The war has come to an end and politicians have begun drafting a new roadmap for the transitional period. The [ratification of the] Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) initiative in 2012 had been followed by a period of political power-sharing within the Yemeni judiciary. In the wake of such a phase, the fact that an entire article of the new agreement is dedicated to judicial bodies and their members is of tremendous significance.

Quota Politics After the GCC Initiative

Following the [ratification of the] GCC initiative, the politics of appointments by quota became widespread among political factions that were new to the government. Accordingly, the Islamist al-Islah party took control of half the seats in the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC), appointing its own partisan members. The latter’s judicial positions did not prevent them from declaring their affiliation with [al-Islah’s] political movement. The remaining half of the SJC seats continued to be held by the heads of judicial bodies affiliated with the old regime, and [with the former ruling party] the General People’s Congress (GPC). The president was also given the right to nominate the head of the SJC from among judges in his entourage.

This resulted in acute divisions within the SJC, and had a negative impact on its work and on its duties. Political loyalty continued to be the sole standard for promotion and appointment. Meanwhile, the SJC submitted to dictates and became incapable of helping the judiciary out of its predicament. In fact, it contributed to weakening the judiciary and eroding its independence even further. Standards of admission to the Supreme Judicial Institute were also severely undermined, as students from politically affiliated community colleges –lacking the most basic requirements for admission and having never studied law– were enrolled.

Back in 2012, judges had nearly managed to reach an agreement with the country’s president regarding guarantees of independence, but their efforts had been thwarted by the practice of quota appointments. The aim of such an agreement had been to form a strong and independent [judicial] administration that would not submit to the dictates of any political power or party. It would have included selecting the members of such an administration in line with standards of competence and integrity, in addition to granting judges the right to nominate three candidates to every judicial position on the basis of such standards.

The pressing question that now arises concerns the potential consequences of the new Peace and National Partnership Agreement. Will the quota-based allocation of positions persist under the label of “partnership”, with a simple redistribution of shares among new actors? Or, will the principle of participation turn into a guarantee of the independence of the judiciary, one that would prevent all forms of exclusion and marginalization?

Representation and Participation

As mentioned above, the new agreement set specific and distinct conditions for partnership. While it stipulated that there be fair representation of all political factions in public administration, it subjected judicial bodies to the principle of fair participation, as per the decisions reached by the National Dialogue Conference (NDC).

There is a big difference between the notion of fair representation and that of participation. Indeed, fair representation signifies political partnership and the appropriate distribution of power. Such an arrangement is based on the principle of power sharing that serve the interests of the mass base of the movements and the parties involved, which in turn determines the behaviour of these actors. Under certain circumstances, such partnerships may coincide with the general national interest. They nevertheless remain mere political alliances that represent the immediate interests of the parties comprising them. Within such alliances, the share of power held by each party is determined by the latter’s political weight and its significance to the survival of the alliance as a whole. This kind of alliance does not usually last very long, and is at its weakest when the fundamental positions and interests of the parties involved are at odds with each other.

Participation, on the other hand, is a completely different concept. It is not about acquiring some form of executive power or reaping calculated benefits. Rather, it signifies everyone’s right to take part in decision-making in the broader sense.[1] Participants should thus have their voice heard in public affairs as a whole, not only in the executive branch of government. Participation represents one of the pillars of the democratic process, whereby groups or individuals can even participate from a position of opposition.

Representation should therefore be understood as a means to obtain power, or to mobilize forces for that purpose. In contrast, participation should be understood as an attempt to have everyone take part in decision-making through various channels. Given that judicial bodies suffer from political partisanship, power-sharing arrangements and quota-based appointments, it stands to reason that participation, as prescribed in the new agreement, offers a more suitable mechanism for reform. In this context, participation signifies several things: the need to grant judicial bodies their constitutional powers; the need to believe in the autonomy of its decisions and actions, as well as its independence vis–a–vis another [public] authority; and, the need to support efforts to fix its current status, in a manner that would inherently prevent any kind of exclusion or marginalization.

Such reform raises the question of who should be heading such bodies. Current holders of these top positions have remained silent over claims concerning their alleged political affiliation. Their silence has entirely stripped them of the garb of neutrality, objectivity and independence. They should therefore be replaced by a new leadership, one that would meet the objective standards required for all leadership positions within the judiciary. Replacements should be made primarily by the community of judges, who make up the third branch of government.

It is to be feared, however, that political forces might seek to impose a different interpretation of [Article 6], one that would lead to replicating the experience of partisan quota-based appointments. Judges in particular should be warned of this, before it is too late.

Putting an End to Political Quota-Based Appointments

In order to implement a new round of quota appointments, political forces will most likely try to circumvent the principle that forbids the dismissal of judges by keeping some members of the current judicial leadership in place. They may resort to several methods to do so. They may pressure some judges into resigning by luring them with promises of appointment to different executive positions. This occurred with the Secretary General of the SJC, the Chairman of the Judicial Inspection Commission, and the Dean of the Supreme Judicial Institute. The political forces involved might also shuffle the posts of certain judges to allow for the appointment of new ones.

Judges must therefore remain vigilant in the face of any such attempt to undermine the independence of the judiciary. Over the coming period, they should work towards regaining the initiative and finding new means to help the judiciary out of its predicament. In 2013, they had successfully revived the Yemen Judges Club – a club capable of bringing them together and uniting them.

It might be more appropriate to call for an extraordinary meeting of the General Assembly of the Judges Club, than to resort to protests and to the streets. The assembly could then authoritatively set the appropriate standards for holding top judicial positions, and select those who would hold such positions through a process of free and direct elections. In order to achieve such a goal, the assembly could rely on the decisions reached by the NDC, and on international principles and treaties regarding the independence of the judiciary. According to these covenants, judges themselves should elect their own judicial leaders.

This would require swift action, in a manner that would embody and reflect the judiciary’s prestige and standing. If such action is delayed, political forces could take advantage of the agreement to maintain those affiliated with them in top judicial positions, and appoint new SJC members from yet unrepresented political factions. Such a course of action is the only guarantee for the implementation of Article 6, and the safeguarding of a strong and independent judiciary. Only such a judiciary would be able to guarantee people’s rights and freedoms during the transitional period, lay the foundations for what will follow, and close the chapter of the past once and for all.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] See: Ahmad Jweid’s, “Political Partnership”:

https://groups.google.com/forum/#!msg/fayad61/tgDU4kxbrlA/1wiCbsEUWYAJ