Union Activism in Tunisia: Legitimate Demands vs Condemnation

Today, some experts, politicians, and media figures loyal to the current government are using the pretext of safeguarding the state (which has been weak following the revolution), ensuring its survival and protecting its institutions to respond to the escalating waves of labor strikes in Tunisia. They have used these arguments against strikes in sensitive sectors like education, health, and transportation. These sectors contain the largest number of state and public sector employees. They also represent the greatest number of members of the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) and the strongest unions within it. Due to their electoral weight, these sectors are the most influential in determining the UGTTs leadership at its national conference.

Critics often imply or directly state that these strikes now threaten to destabilize and bring down the state, due to their frequency and lengthy duration. Some even go so far in their condemnation and vilification as to connect the strikes to the threat of terrorism. This occurred when teachers and professors were accused of sowing confusion within the security “institution”, which is waging a fierce war against terrorism. Naturally, this argument is readily invoked whenever strikes coincide with the successive [terrorist-designated] attacks that the country is witnessing, the most recent being the horrific Sousse incident.

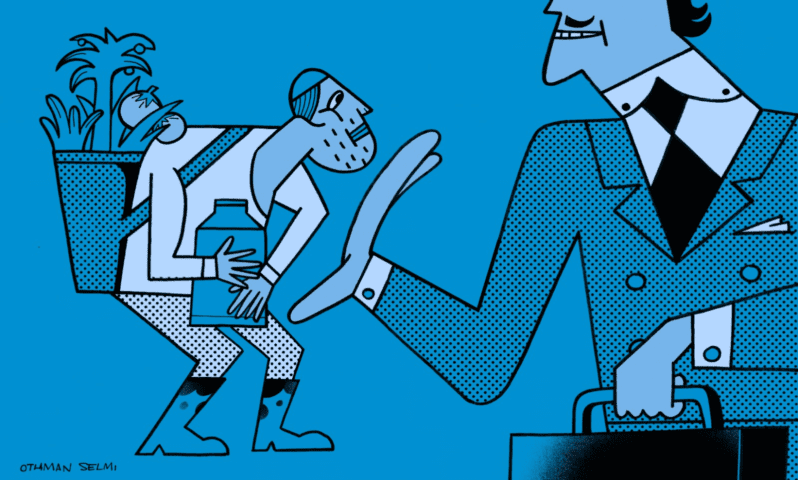

Many articles published by daily and weekly papers and websites eager to cover provocative topics are discussing the union issue. Many of these articles denounce the legal strikes and the snap, illegal strikes [al-idrabat al-wahshiyya]. With the exception of the newspaper of the nationalist and Marxist left (the mouthpiece of the Popular Front), the press has been broadly distrustful and critical of the workers’ organization. Sometimes its disapproval is frank; at other times, it is hidden behind facades of support. Often, the press tries to drag the unions into serving purposes other than those for which they were created, all in the name of “the state of the national economy”, “the prestige of the state” and slogans of national solidarity, in order to put workers further at the mercy of employers.

How Can We Explain the Increase in Labor Strikes?

There are a number of complex reasons for the rise in social activism in the form of labor strikes in Tunisia. A major cause is the injustice that workers faced throughout the rule of deposed President Zine el Abidine Ben Ali. Following the revolution, many groups and sectors saw the weakness of the state’s authority and the UGTT as an opportunity to realize some of their demands. This led to the use of strikes as a tool to protest (sector-based strikes calling for better wages, and local and regional strikes calling for development) or to pressure the government into meeting general demands, or the demands of particular groups. These reasons can be summarized as follows:

Unionist Demands

The striking unionists usually accuse the state of reneging on earlier agreements. In their view, the state should not renege on its pledges irrespective of the circumstances that the country is witnessing, because it should, in all cases, continue acting like a state and stand by its commitments. These unionists adhere to this point of view even though they all know that for political reasons, earlier governments have made agreements that they fully understood later governments would be unable to implement; this is the height of irresponsibility with which a number of officials behave.

The behavior of the state, as an employer on the one hand and an arbitrator between all sides on the other, is often marked by duality. The Tunisian government generally signs special agreements outside the scope of general negotiations, both in the public and private sector. It cannot totally neglect these agreements. However, to limit their effectiveness, it tries to circumvent them in application.

The call for wage increases via increases in special allowances, outside the scope of general negotiations, in order to mitigate the drop in buying power and the impoverization of large sectors of the middle class.

In its most recent study published at the end of 2014, the Centre for Economic and Social Studies and Research in Tunisia indicated that the “new poor” constitute around 30% of the total number of poor people in Tunisia (estimated to be 2 million of the country’s 10 million inhabitants). The study defined the new poor as “junior staff in official departments, primary school teachers, and workers and employees whose monthly income does not exceed TND700 [approximately USD$450]”.

These two demands may sum up the factors that pushed professors, teachers, and health officials, for example, to use an extreme form of protest such as administrative strikes. Such strikes involve continuing work but refraining from completing any administrative tasks, such as administering exams in the case of teachers, and carrying out financial transactions as patients are admitted in the case of health officials. Workers and officials in Tunisia resorted to this kind of unusual type of strike to make their voices heard by the government and society after negotiations faltered and earlier strikes -as a means of applying pressure- failed to yield benefit. Despite this, many people that are far removed from legal and unionist logic, view these strikes as a kind of extortion practiced against a weak government that may be forced to yield to the workers’ demands. Some also believe that the teachers are holding their students hostage in their conflict with the supervising authorities, and that health officials are sabotaging the state budget by depriving it of revenue from public hospital treatments.

The Spread of Unemployment and Marginalization

Before the revolution in Tunisia, a new form of employment contract appeared. This form, the short-term contract, pandered to the need of businesses and the state to control the workforce. It did not only appear in the private sector, rather, the state itself also began using such contracts. Naturally, the formal appointment of these contractors, both in unadvertised civil service positions or in private firms in general, is subject to stalling and extortion and is even contingent on the loyalty they display for the government or employer. Similarly, the use of foreign labor via labor firms and temporary work agencies (i.e., subcontracting companies) became widespread. These forms of work have been instrumental in shaking up job centers, spreading unemployment, and even curtailing the social interests of the working class. They have also caused a large percentage of workers to forgo union membership, because they prioritize their personal interests over public struggle.

In addition, the turbulent social, economic, and political situation that Tunisia experienced after the revolution led to a drop in domestic investment. Many foreign investors also left on account of the many protests and strikes that have beset firms in the country. Furthermore, Tunisia recently lost a major deal when PSA Peugeot, a company promising to employ 50 thousand workers directly and indirectly, decided to set up shop in Morocco instead of Tunisia. According to the aforementioned study, this situation has resulted in an increase of approximately 30% in the poverty rate over the last four years, and the rise of unemployment to 40% in some disadvantaged regions. This explains the regional activism that, following the disappearance of some sections of the middle class, has occasionally led to violent confrontations with the security forces and arrests, which further exacerbate the situation.

Union Action Administered from the Bottom as Opposed to the Top

The rules of union action changed in Tunisia after the revolution. Before the revolution, the UGTT, through its executive bureau and administrative body, colluded with whatever government was in power at the time to tightly control any social activism. The country witnessed -especially during the era of Ben Ali- a kind of equilibrium built upon a convergence of interests. For the UGTT, the state allowed workers to receive raises every three years after periodic negotiations with the union. The state also made deductions at source for the benefit of the labor organization, monopolized union representation, and occasionally rendered suspicious services to union officials usually accused of corruption. In return for all of the above, the organization controlled the zeal of the workers and gave its loyalty to the ruling president through its administrative body (which the leadership controls by feeding the ambitions for career advancement and responsibility that most members possess).

All of this changed after, or perhaps during, the revolution. The executive bureau dealt with the uprising with great caution and reservation, whereas the general unions and the regional and local unions strongly supported it and opened their doors to the revolutionaries. They then successively joined regional strikes that concluded in the Tunis Regional Union’s strike on January 14, which resulted in Ben Ali’s flight and the fall of the regime. This change in the form of action, and its shift from the top of the pyramid of union authority to the bottom, broadened the scope of the strikes. The major unions and the local unions marginalized before the revolution joined in alongside the general unions and regional unions, which further expanded the scope of the strikes.

The most dangerous, and unprecedented development may be the general local and regional strikes, which paralyze all sectors at the delegation and governorate levels. This type of strike is not subject to any kind of legal control. Naturally, the UGTT is forced to support these strikes or turn a blind eye to them as it is unable to control them in any way, especially given the trade union pluralism that appeared after the revolution. This pluralism has become a deep wound or Achilles heel in the organization’s body. Union officials lament the matter in their closed circles, unable to acknowledge it openly. The issue will no doubt be exacerbated by the ruling that the Administrative Court issued on June 26, 2015. This ruling granted the General Confederation of Labor (CGGT), a rival of the UGTT, the same rights that the UGTT enjoys. These include the right to deductions at source from the wages of workers and officials who declare their membership in this or that union organization.

In sum, a reading of the internal logic of the union movements reveals a number of important implications. The most notable is that alongside the legal strikes that adhere to the law’s provisions (primarily, the requirement to provide prior notice and obtain the UGTTs approval), there are a large number of strikes that are distinguished by their spontaneity, their lengthy duration, and, occasionally, the unrealistic nature of their demands.

Are These Strikes Helping to Improve Workers’ Circumstances?

Are these strikes easing the suffering of workers and state employees who represent the middle class, and helping to ensure that they can enjoy all their rights, including the right to suitable working conditions and the right to a decent standard of living? Asked differently, is it possible for these demands, which some see as unfair, be dealt with from the perspective of the state budget and the depletion of its resource? Can they be dealt with using a discourse that vilifies, makes accusations of treason, and incites public opinion against the striking sectors in the media and negotiation sessions? Can they be dealt with, as some have done in the wake of the Sousse attacks, by calling for a state of emergency, which would entail suspending all protest actions, labor strikes, and sit-ins and declaring a state of war against terrorism?

Today, some politicians and media figures known for their loyalty to the past or present government dream of a return to the old methods, to the policy of repression and threats to deduct workers’ wages or disqualify them from employment, and to the logic of subjugation. On occasion, calls have even been made for martial law to be declared and for the Constitution to be suspended on the basis that the country is in a state of war and the laws of war apply. These calls are no doubt irresponsible. After the Sousse incident, Sami Tahri, deputy secretary general of the UGTT, responded to them by stating that “the strikes and social actions did not contribute to the growth in terrorism. Those who did contribute to its growth are the people who said that the terrorists play sport” (a reference to the Islamists during the rule of the Troika). Tahri also responded to Lazhar Akremi, a member of the ruling Nidaa Tounes party who, on one of the private television channels, called for social calm so that the security forces can focus on combatting terrorism. Tahri stated that “terrorism should not be exploited in order to target the right to strike and social protest, which are guaranteed by the Constitution”.

Confronting the Crisis: Some Final Thoughts

Aside from the calls that could lead to internal strife, there is now a consensus in Tunisia that the state must take unpopular measures to confront the stifling crisis that the country is experiencing. These measures including freezing wages (even if only for a brief period), reviewing compensation policies, raising the prices of certain goods, and increasing the VAT rate. On the other hand, the work climate must also improve, unionists must cease making unfair demands, some of the sectoral agreements that could further burden the state must be rescheduled, and some development projects that are no longer a priority must be postponed. However, the UGTT must also revisit the trade union scene with more judiciousness and responsibility, and firmly oppose the illegal, spontaneous strikes. Secretary General Houcine Abassi has stated this much at many unionist events, and the organization was compelled to make a stand when it referred some rail transport unionists to the Internal Order Committee after they carried out an illegal strike in May 2015.

The pressing question, however, is whether workers and junior officials will accept these measures when they will, as usual, be the first ones adversely affected by them. They stress through their organization that the sacrifices should be made by all, and that the wealthy class in Tunisia is unwilling to help bear the burden of the crisis. This class has constantly behaved in such a manner by practicing fiscal evasion, which has been the bane of the Tunisian economy over the past decades, and remains so today. The UGTT usually summarizes the call for fiscal reform with the slogan “Whoever earns the most sacrifices the most; Whoever earns the least sacrifices the least”.

In any case, there is now a pressing need to begin a prompt national dialogue about economic and social issues in general, and the topic of terrorism in particular. The only choice today is to frankly inform the Tunisian people of the details of the crisis and the existence of a communal will to agree on the solutions that the nation’s parties and major organizations must reach. Negotiating these solutions must go beyond the political bickering and accusations of responsibility leveled against one side or another. Either we rescue the ship together by way of collective effort, or we all do down with it.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.