To Pit Agriculture Against Tourism: The Case of the Zahrani Coast

I remember well the weekly trips south that I took with my family when I was younger. I would sit in the back seat on the right and look out, observing the road in all its details and its intermittent ocean views. That was during the 1980s, before the southern highway was built. We would take the ocean road that passes through several towns of the Zahrani district. We always stopped at the Abu Maher butcher in Sarafand and at Abu Ashraf in Adloun to buy the famous Adlouni watermelon. Sometimes we would stop for lunch at Khaizaran al-Kabir, a restaurant overlooking the Saksakiyeh beach. Khaizaran is the waterfront of the town Saksakiyeh, which had long attracted sea-goers and fresh fish-lovers from distant areas such that the entire coast stretching from Aqbiyeh to Adloun, passing through Sarafand and Ansariyeh, came to be known as the “Khaizaran Sea”. I remember them as towns brimming with life and shops lining the roadsides.

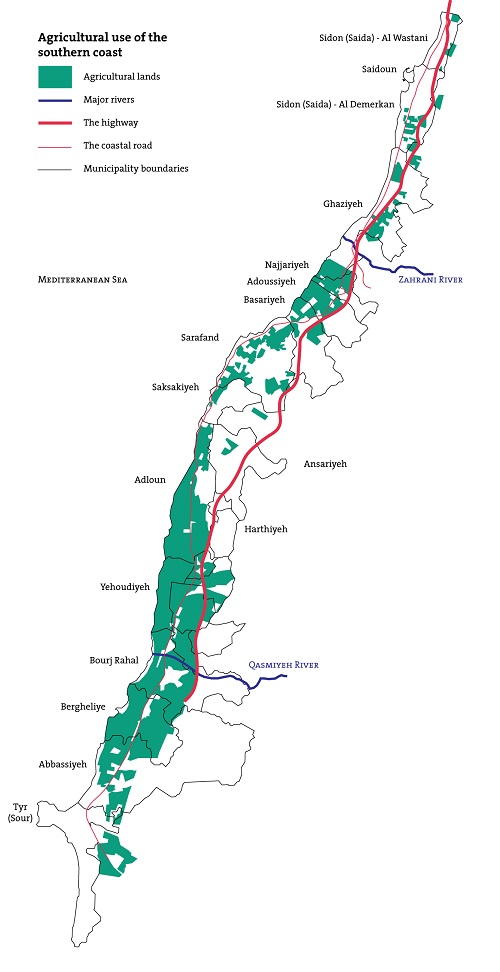

The years passed, the freeway was built, and traffic diverted to it. With this change, an unfamiliar and epic sight appeared before me: the vast agricultural plain on the Zahrani coast between the cities of Sidon and Tyre.

This sight, which amazes all who pass along the highway, raises many questions: Why has the agricultural plain remained as is, and what is its future given the real estate “boom” sweeping across every patch of land from the north to the south? How has the southern highway affected these towns? And have the planning interventions reconciled and harmonized between the region’s various economic potentials, from agriculture to fishing to domestic tourism?

Diverse Economic Components and Potentials

The vital economic driving force of the Zahrani coast’s villages has long been agriculture. Historically, two thirds of the area of each town was used for cultivating citrus fruits and banana, in addition to other produce such as corn, wheat, other fruits, and vegetables.[1] The high-quality soil and the Litani River irrigation, drainage, and drinking water project that began in 1951 were key factors underpinning the intensive agricultural activity spanning the entire region from Ghazieh to Qasmiyeh. The coastal lands benefited from the Litani River’s irrigation channels. Of course, Palestinians played a role as they had experience in this means of irrigation. When they came to Lebanon (especially those from Jaffa), they worked the land and established a paradigm of agricultural work.[2] Additionally, Lebanese citrus fruits – the main product of the Zahrani plain – found key outlets in the Arab markets during the 1960s and 1970s. Adloun was an exception as its farmers produced, in addition to citrus fruits, Adlouni watermelon, which has been farmed there for more than a century.

Marine activity such as fishing was also an important economic factor for some of the towns, especially Sarafand, where there are two finishing ports (Zahrani and Ain al-Qantara) home to approximately 200 boats. Fishing is one of the main sectors of Sarafand’s economy and sustains approximately 700 fishermen in the region, who come from Ghazieh, Adloun, and Saksakiyeh to practice their profession. The Fishermen Cooperative of the Zahrani Coast was established in 1991, and today it includes 162 members. The cooperative is a fish market where 85% of the fishermen offer their fish for sale.[3] To this day, the fish markets remain an extremely important business in Sarafand, for the town hosts seven of them.

In parallel to agriculture and fishing, domestic tourism also developed in the Zahrani coast’s towns because of their proximity to the beach. The cafes and restaurants overlooking the “Khaizaran Sea” flourished (at intermittent stages, particularly during and before the 1970s). The coastal groves were another factor attracting visitors to the region. Families from Beirut would come to spend the day, and Arab tourists would come to the Khaizaran beach from their summer vacation spots in Bhamdoun and Aley.[4] During the 1975-1990 Civil War, before the southern highway was built, vehicle traffic on the coastal road increased, as did the shops, which became a source of income for the people who did not leave their towns during the war.

The situation changed and during the last two decades, the region witnessed large waves of departures as residents moved to Beirut or left the country. Consequently, most of the voters registered in the Zahrani coast’s towns are absent throughout the year. The emigrants transfer money to their families, which have become largely economically dependent on their support. Like the other parts of southern Lebanon, the region has received limited developmental interventions since modern Lebanon was formed. It has also suffered from regional conflicts, including multiple Israeli invasions.

Today, the economy of the Zahrani coast’s towns still relies on agriculture, fishing, and light local tourism. However, these sectors – especially agriculture – are not as productive or effective as they used to be. Farmers complain of insufficient government assistance and direction and an absence of a regular market for agricultural production. Similarly, fishermen complain that the fishing sector is under threat because of the deterioration in the quality of marine life due to the dumping of wastewater and solid waste into the sea and because of inadequate assistance for buying tools and equipment.[5]

Dysfunctional Urbanization: The Case of Sarafand and Adloun

The Zahrani coast’s towns are increasingly experiencing dysfunctional urbanization, especially due to the absence of regulations or comprehensive general master plans. To this day, the region falls within the “unplanned areas” category.

The 1973 decree titled “Overall General Master Plan for the Southern Shores Area” planned the region’s plain for touristic use, leaving the rest of the lands unplanned. What does this mean in practice? The construction of all kinds of buildings in Lebanon requires obtaining a permit in advance. In this regard, the Building Law differentiates between construction in planned areas and construction in unplanned areas. Planned areas are those for which general and detailed master plans and regulations ratified via decrees by the Council of Ministers have been put in place.

To begin with, let us take a critical look at the southern shores decree. From one angle, the decree partially planned the areas, drawing borders that geographically divide the towns on flimsy bases. In the case of Adloun, the decree adopts the railway as a reference, classifying the areas west of it as “tourist” while classifying lands extending several meters east of it – despite decades of agricultural use – as a “second extension” area, thereby allowing future urban expansion in them. From another angle, the tourist classification of the agricultural lands parallel to the shore is in itself problematic. Firstly, the classification does not protect agricultural areas, as opposed to tourist areas; rather, it renders them all open to construction. Secondly, the decree defines the tourist areas as being for private housing, restaurants, and tourist establishments, setting exploitation ratios (which define the permitted size of a building given the size of the underlying property) higher than those found in other parts of Lebanon (20% surface exploitation and 0.4 total exploitation versus, for example, a maximum of 15% surface exploitation and 0.2 total exploitation in Area 10 of Beirut’s shore). From here stems another issue: The decree renders obtaining building permits in this area contingent on acceptance by the Higher Council of Urban Planning (HCUP). Consequently, it is difficult for anyone who – unlike the owners of major projects – lack connections in or knowledge of the public administration to make use of the decree’s provisions.

As for construction in unplanned areas (which account for 85% of Lebanese territory), the HCUP’s 2005 decision regulating construction, subdivision, and exploitation in unplanned areas is applied. The decision set the maximum surface exploitation ratio at 25% and the maximum total exploitation ratio at 0.5 in any plot of land, whether it is situated on a mountain, on a plain, or in the middle of a town.[6] This led to urban sprawl that does not take into account the nature of the land or community in all parts of Lebanon.

Under this legislative framework for urbanization,[7] the partial planning of the seafront in Sarafand and Adloun (via the 1973 decree) and the choice to keep the towns’ other lands unplanned has had several catastrophic consequences:

- During the last 30 years, there has been much construction at the expense of natural and agricultural areas. In Sarafand, for example, urban sprawl constituted just 4.5% of the total area in 1975, but by 2002 that percentage had risen to 25.5%.[8]

- During the war years, small shops and workshops proliferated densely along the shore. Private tourist complexes were built along the borders of the remaining beaches, preventing free access to the beach. Additionally, a tourist port project has begun on Adloun’s shore.[9]

- Sarafand, in particular, witnessed an increase in encroachments on public maritime domain. These constructions began during the Israeli occupation of the south. The inhabitants of the occupied villages fled to Sarafand and erected houses informally. However, the construction intensified in the years that followed, paving the way for further urbanization of the shore.

- Despite the virtues of Sarafand and Adloun (beaches, historical sights, fishing ports, and restaurants), tourist activities in them have rarely developed.

General Master Plans in Effect Despite Never Being Issued

In 2008, the HCUP adopted decisions entirely planning Sarafand and Adloun for the first time. However, it did not publish them in the Official Gazette. Interviews we conducted in the region revealed that the residents are not aware of their existence. What do these two plans do?

In Sarafand, the plan is in line with the changes that have occurred in land use. It changed the agricultural classification of approximately half the coastal plain (where urbanization had begun) to “residential extension”. It retained the previous tourist classification of the waterfront, and it retained the agricultural area west of the old town.

In Adloun, the plan consolidates the tourist classification of the waterfront and all the previously mentioned issues arising from it. The plan classified the lands serving agricultural uses east of the coastal road (some of which had been classified urban extension areas) as agricultural.

However, the HCUP decisions pertaining to the plans were not issued via Council of Ministers decrees within the deadline of three years from their initial adoption. Hence, in principle, the decisions are expired and have no effect (per Article 13 of the Building Law). In practice, however, the administrations are still applying the decisions to this day. From here stems another, extremely important issue, namely that keeping a plan in the form of a decision facilitates the process of making changes and issuing exceptions to it. In the case of Adloun (see the diagram), since 2008 the HCUP has issued a number of decisions granting property owners amendments and exceptions in favor of real estate investment. These decisions pertained not to a few properties of limited size but to vast areas encompassing properties owned by people with no connection to the town (as shown by the map). As for Sarafand, the land ownership map shows that approximately 50% of all lands and 80% of the agricultural lands are owned by people not from the town.

In Adloun, resident Mr. Abdullah Ibrahim explains why this situation exists:

Most of the landowners in Adloun aren’t from the town because the lands were generally fiefdoms during the Ottomans’ time. People didn’t see landownership as important, and the taxes were expensive. They would easily barter land for horses, goats, cattle, or small sums of money. Who was paying attention? City folk, who were buying the lands from the Adloun farmers who owned them.

As for during the last few decades, especially in the 1990s, investors or businessmen came and bought lands in Adloun. Examples include the Hariri, Jaafar, and Khalil families. Adloun is considered the best coastal agricultural plain in Lebanon, and citrus fruits are its most important produce. There is a desire to invest in the produce and to own [land] here. Most importantly, don’t forget the early 1990s, when politicians/investors believed that we were heading toward peace with Israel. Hence, at the time these southern lands seemed like a good area for investment, and a movement of buying and selling land began during the first Madrid negotiations, as well as after Oslo.

The identity of the landowners has a large influence on the choices made in land-use plans and the orientations must be adopted to achieve sustainable social and economic development in both Sarafand and Adloun. Usually, agriculture and natural resources are pitted sharply against economic development, the argument put forward being that major tourism projects will bring employment opportunities for the region’s youth. What about agriculture and the environment?

Economic Arbitration: Debates About Development Models

Conserving natural resources (the shore and the agricultural plain) to enable future generations to benefit from them should not be pitted against opportunities for employment and financial profit. Despite the absence of any agricultural classification for the Zahrani plain (before 2008), the lands remained predominantly agricultural for decades because of the people’s use of them. In reality, Zahrani’s agricultural coast can produce indefinitely, and agriculture can help combat emigration abroad and rural exodus.

Conversely, selling agricultural lands for private real estate investment brings quick profit to the investor but leads to the disappearance of agricultural lands forever.[10]

Job creation is doubtlessly important for ensuring a harmonious division of the wealth stemming from the local resources. Hence, it is important to compare the types of employment opportunities arising from different paradigms of economic and social development. In this regard, we should be aware that the employment opportunities available in the context of tourist services are remunerative to some extent, specifically if we assume that the owners of the tourist resorts will employ locals.

According to a report that the United Nations Environment Programme produced with the Ministry of Environment, resort owners have many reasons not to employ locals. These reasons include the high cost of local labor compared to migrant labor, the better work conditions demanded by the former, the absence of government control encouraging local employment, and the interference of local political authorities in the local employment process via clientelism and personal connections.[11]

These employment opportunities must be compared to those that could be provided via agricultural development. They include opportunities for independent farmers, engineers, agricultural consultants, merchants, transport owners, agricultural equipment operators, technicians, and more, as well as the opportunities in the agri-food industry.

From the domestic tourism angle, it is astonishing in a country like Lebanon – whose people are prepared to move around – for local communities not to see the need to develop their special features so that they can compete with other regions. The Lebanese have, in fact, begun traveling dozens of kilometers to explore green, coastal, and mountainous areas, fleeing the concrete cities and the enormous resorts associated with an outdated conception of economic development. The beaches of Tyre, Batroun, and Byblos provide an example of local residents benefiting from this kind of domestic tourism. But in Zahrani, the virtues enabling the region to compete economically have disappeared. Consequently, few people now head to Sarafand and Adloun to swim or enjoy lunch. Thus, the plans for Sarafand and Adloun – and the amendments made to them – were a lost opportunity to establish a vision based on arbitrating between the region’s various economic potentials, which are not necessarily incompatible.

Special thanks to architect Ali Wehbe who helped with research and supplied us with valuable information about Adloun.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

This article was originally published in Arabic as part “Master planning in Lebanon: Manufacturing of Inequality” (July 2018). This publication is the outcome of a research project by Public Works Studio in collaboration with the Legal Agenda.

Related articles:

Planning Zouk Mikael: Ignoring the Power Plant of Death

The Legislative Framework for Urban Planning: No Voice for the People

Master-Planning in Lebanon: Manufacturing Landscapes of Inequality

[1] Marwa Boustani, Estella Carpi, Hayat Gebara and Yara Mourad, Responding to the Syrian crisis in Lebanon: Collaboration between aid agencies and local governance structures, IIED Working Paper, IIED, London.

[2] Interview with Abdullah Ibrahim, a resident of Adloun.

[3] Responding to the Syrian crisis in Lebanon, op. cit.

[4] Nazmiya al-Darwish, “Maqahi Khayzaran: Zaman al-Awwal … Tahawwal!”, Al Akhbar, July 31, 2017.

[5] Sawsan Mehdi, Coastal Area Management Programme (CAMP) Lebanon: Final Integrated Report, Priority Actions Programme/Regional Activity Centre (PAP/RAC), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Lebanese Ministry of Environment, 2004.

[6] Before 2005, this ratio was higher (40%/0.8).

[7] See also Karim Nammour, “Faragh Tashri’iyy Yatafaqam min al-‘Amm 2004”, The Legal Agenda, is. 53.

[8] Coastal Area Management Programme (CAMP) Lebanon, op. cit.

[9] For more about the port under construction in Adloun, see Rola Farhat, “La Sayf fi ‘Adlun Hadhihi al-Sana”, almodononline, February 3, 2016.

[10] Interview with architect Eli Khattar, head of the Strategic Plan in the Federation of Sidon and Zahrani Municipalities project.

[11] Coastal Area Management Programme (CAMP) Lebanon, op. cit.