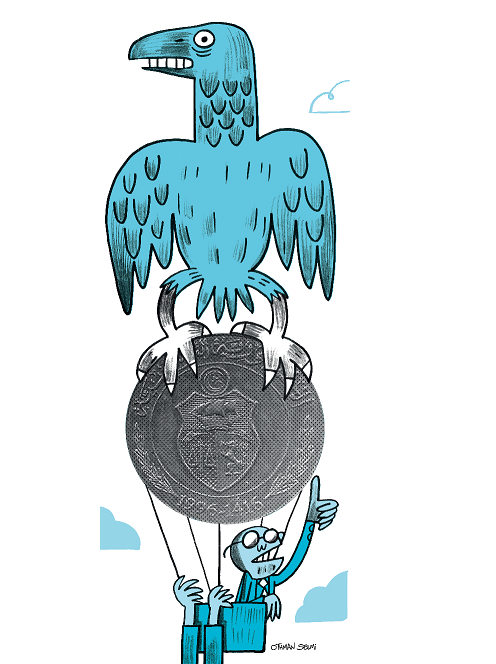

The Tunisian State Amputates its Monetary Arm

During the last five years, the Tunisian financial and banking sector witnessed radical changes after the outgoing Parliament approved a series of reforms that redefined the state’s role and areas of intervention in the financial market and banking sector. The process launched after the beginning of a comprehensive audit of public banks was announced in 2013.[1] The audit coincided with then Minister of Finance Elyes Fakhfakh’s signing, in the company of former Central Bank Governor Chedly Ayari, of the “document of intent”. This document laid out the major themes of the comprehensive program for structurally reforming the Tunisian economy and public sector primarily in accordance with the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) recommendations, which was a condition for Tunisia to receive the Extended Fund Facility loan of US$2.8 billion paid in installments over the past five years. However, the modifications that the banking sector’s legislative framework witnessed, particularly the law regulating the Central Bank, would prove over the same period that the state had merely amputated its financial arm. These laws, which the former director of the Central Bank defended on the basis of, in his words, “the need to respond to the demands of modern monetary governance” and end the financial institutions’ subordination to “the mood and dictations of politicians”, would be one of the main factors exacerbating the economic crisis and Tunisians’ misery.

The Structural Reforms in the Banking and Financial Sector: A Necessity or Submission to Pressure?

Since the Tunisian government resorted to the IMF, reforming the banking and financial sector has constituted one of the IMF’s main conditions for obtaining loan installments. In 2013, the Tunisian government committed to a series of structural reforms per a schedule that included capitalizing the public banks, bolstering the Central Bank’s independence, and reforming the banking sector and financial institutions.[2]

The first step was the approval of Law no. 31 of 2015 on Bolstering the Financial Solidity of the Banque de l'Habitat [Housing Bank] and the Société Tunisienne de Banque [Tunisian Bank Society] (21 August 2015), known as the “public banks recapitalization law”. The bill had failed before the National Constituent Assembly in September 2014 even though it had previously agreed to allocate the required funds in the 2014 Finance Law Supplemental to 2013. Parliament later expanded the scope of this law, via Law no. 36 of 2018, to encompass all public banks (i.e. implicitly adding the Banque Nationale Agricole [National Agricultural Bank]) and allow them to negotiate over unpaid debts and reach settlements on certain conditions, excluding loans granted without collateral and those connected to suspected corruption.

Subsequently, the banking and financial sector reforms accelerated. In April 2016, Parliament approved a bill on the statute of the Tunisian Central Bank, replacing the 1958 law. Article 2 of the new law stipulated that the Central Bank is “independent in achieving its goals, performing its functions, and managing its resources” and that “the Central Bank’s independence cannot be impinged upon, nor can influence be exercised over the decisions of its bodies or its personnel in the performance of their functions”.

The Central Bank’s statute, known in the media as the “Central Bank independence law”, stirred controversy by implicitly separating between monetary policy and the state’s financial policy and stripping the latter’s monetary arm,[3] especially as the same law prohibited the Central Bank from directly lending to the state on the basis that it could exacerbate inflation. Recently, this controversy resurfaced when the Future Bloc submitted a bill abolishing the 2016 law’s provisions and the People's Movement made its participation in the government contingent on a review of the Central Bank’s independence.

On 12 May 2016, less than a month after the Central Bank statute was adopted, Parliament approved a bill pertaining to banks and financial institutions without the MPs being able to study it sufficiently. The General Assembly began examining the bill just one day after the Financial Committee finished working on it and approved the bill within two days. The protests of opposition MPs, particularly the Popular Front MPs and their request for a one-day extension to scrutinize the bill, were rejected on the basis that the law had to be approved before the IMF’s Executive Board convened on May 13.[4] The Provisional Instance to Review the Constitutionality of Draft Laws deemed the procedures whereby the bill was approved – particularly the way it was referred to the General Assembly, which did not comply with Article 138 of the internal statute – to be unconstitutional. Hence, it returned the bill for reapproval.[5]

Hence, between 2015 and 2016, the government and MPs of the governing coalition at the time (Ennahdha and Nidaa Tounes) complied with the structural reform program engineered by the IMF. In less than two years, three main recommendations, namely capitalizing the public banks, bolstering the Central Bank’s independence, and reforming the banking sector and financial institutions, were implemented. The hasty implementation was a consequence of carrot and stick logic: with the escalation of the economic crisis and severity of the protest movement, particularly in the winters of 2015 and 2016, Habib Essid’s government was increasingly yearning for the life-saving doses that the IMF was waving in the form of installments delivered in accordance with the pace of the implementation. However, over the following three years, these analgesic doses would have disastrous repercussions on the various economic indicators such that the country today is suffocating more than before.

After the Reform: The Collapsing Dinar Brings Down the Other Indicators, and the Central Bank is Sidelined

Following the success in “modernizing the financial and banking system”, in the words of former Central Bank Governor Chedly Ayari, the national currency was the first to pay the price. The Tunisian dinar lost 30% of its value over the last five years, with its exchange rate falling from 1.95 to the US dollar in October 2015 to 2.84 to the US dollar in December 2019. This catastrophic collapse was an inevitable consequence of leaving it up to supply and demand to determine the exchange rate. In other words, the national currency is beyond the reach of any direct state intervention such that its exchange rate is determined by the balance of trade.

This decision was taken without the least consideration for the trade imbalance that – for years and to this day – had caused a continual deficit in the balance of payments. While this deficit was TND12.003 billion during Q4 of 2015, it reached TND19.049 billion in Q4 of 2019. In other words, the collapse of the dinar’s exchange rate was a direct cause of the increase in the trade balance deficit, and the yearly expansion in the deficit due to the rising value of imports automatically contributed further to the shrinking demand for the Tunisian currency and, subsequently, the negative effect on its value. This created a vicious cycle of reciprocal negative effect.

The repercussions of the dinar’s declining exchange rate were not limited to its effect on the result of trade. Rather, they also struck the Tunisian citizen’s purchasing power as the country imports a significant portion of its basic consumables (basic food imports exceeded TND3.890 billion in 2019), whose prices at the time of import rise when the national currency depreciates. The direct result is a rise of prices at the time of consumption and accelerated inflation, which increased from 4.8% in 2015 to 6.7% by September 2019.

The direct effect of the dinar’s depreciation also encompassed the size of public debt and foreign debts. In other words, the public budget deficit is no longer the main reason for the rise in indebtedness. Rather, the national currency’s declining exchange rate led to an increase in the Tunisian state’s debts by 49.87% between 2015 and 2020 and to an accumulation of public debt. Public debt will reach TND94.068 billion in 2020, which represents 74% of the GDP, given the rise in the cost of debt payment and the percentage it constitutes of the state’s budget. The ultimate result was that successive governments turned to retrenchment to maintain an acceptable deficit percentage, retrenchment that primarily encompassed development expenditures and support allocations and recruitments in the public sector. Although the causes of the economic crisis were multidimensional and multifactorial, the neutralization of the Central Bank inevitably exacerbated the damages, particularly on the level of the national currency’s collapse and its repercussions. Note that the Central Bank had intervened in May 2013 to halt the depreciation of the Tunisian dinar, injecting TND1.887 billion into the exchange market and adjusting the exchange rates. This measure made it possible to stop the depreciation and curb its negative repercussions and helped provide the liquidity needed to honor the country’s domestic and foreign financial commitments.

The gravity of the financial and banking sector reform also appeared clearly in the state’s turn to borrowing from local commercial banks to fill the deficit in the public budgets and mobilize financial resources with foreign currency three times within two and a half years (€250 million on 6 July 2017, €365 million on 31 March 2019, and €455 million on 1 February 2020). All these loans were to be repaid with hard currency over three years from the date of disbursement at rates ranging from 2% on annual installments for some banks and 2.25% in bulk for others.

The debate over these loans relates not to the technical dimension consisting in the difference in interest rates if Tunisia were to borrow from abroad or the issue of mobilizing public resources; rather, they are directly connected to the series of laws and financial measures that were adopted in 2015 and 2016 under IMF pressure. The resort to the commercial banks came one year after the approval of Law no. 64 of 2015 on the Tunisian Central Bank’s statue and pursuant to Article 25 of that law, which stipulates that “the Central Bank may not grant the public treasury overdrafts or loans or directly acquire securities issued by the state”. In simpler terms, this article prevents the state from diversifying its sources and constricts the options for self-financing via the Central Bank at low rates.

Amid the economic crisis that continues to this day, the governments of Habib Essid and Youssef Chahed chose to look for quick solutions that soothe the populace’s anger via doses in the form of loans, albeit at the expense of national interest. The last five years were distinguished by a prominent theme: eliminating the state’s role in the banking sector, amputating its financial arm and ability to perform a moderating role in the financial market, and compliance with the IMF’s structural reform program to the letter. The IMF’s recommendations were not limited to the financial and banking sector; rather, it sought to impose its conceptions on all the various sectors amid total government submission to the international prescription for saving the Tunisian economy – a prescription that, as the numbers have proven, subsequently forced both the government and the people into a corner.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Tunisia, Banking, Debt, Central Bank, IMF

[1] The public banks represent 40% of the banking sector, and the banking assets from these banks contribute 23% of the total financing for the various economic sectors. Financing in the form of loans encompasses 23% of tourism and 30% of the industrial sector. Similarly, the loans granted to farmers reached TND200 million by 2018. As for employment, the government banks currently employ approximately 9,000 people, and they contribute 3% of the GDP.

In relation to the public banks, unpaid debts reached TND5.9 billion in 2018, while their losses approached TND2.5 billion in 2018. These financial institutions were drained as a result of their exploitation to finance companies tied to former president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s family with sums amounting to TND1.75 billion, and 30% of these sums were provided in cash without any guarantees of repayment.

After the comprehensive audit finished in 2014, the fate of these banks remains unknown despite repeated government allusions, most recently in 2017, to the need for privatization in the face of total rejection from the La Fédération Générale des Banques et Etablissements Financiers [General Federation of Banks and Financial Establishments] of the government options proposed.

[2] Mohammed Samih Beji Okkez, “Qurud Sanduq al-Naqd al-Duwaliyy: al-Mal Muqabila al-Ta’a al-'Amya'”, Nawaat, 26 April 2016.

[3] Mohammed Samih Beji Okkez, “Qanun al-Nizam al-Asasiyy li-l-Bank al-Markaziyy: Istiqlaliyya 'ala Hisab al-Sayada”, Nawaat, 13 April 2016.

[4] Mohammed Samih Beji Okkez, “Qanun al-Bunuk wa-l-Mu'assasat al-Maliyya: Khutwa Jadida ‘ala Sikkat Sanduq al-Naqd al-Duwaliyy”, Nawaat, 12 May 2016.

[5] Provisional Instance to Review the Constitutionality of Draft Laws Decision no. 2 of 2016 on the Banks and Financial Institutions Bill (24 May 2016).