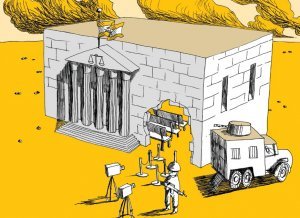

The Special Tribunal for Lebanon: The Rule of Judicial Exceptionalism

The assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri caused a rift among the country’s active political forces over the establishment of an international Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL).

Headed by the so-called March 14 Alliance, STL supporters argue that this tribunal is necessary to combat impunity and put a stop to the cycle of killing, which they consider to be targeting them as well as democracy in Lebanon. Despite voicing reservations about some of its specifics, those now opposed to the STL including the March 8 Alliance, had initially responded positively to the notion of such a tribunal. Yet, they quickly began to view it as a political weapon aimed against them and against Lebanon’s sovereignty. Naturally, their reservations increased after charges of contempt of court were brought against al-Akhbar newspaper and al-Jadeed television station by the STL in April 2014.

Nonetheless, both sides remained unable to provide logical and consistent answers about the problems raised by these crimes in Lebanese public discourse. Indeed, the discourse of STL supporters remained devoid of any clarifications about how the tribunal’s work could be used to end impunity. Meanwhile, the opposing discourse remained devoid of any alternatives to the STL that would ensure the application of justice. In this respect, the discourse of both parties provide is devoid of any practical plans to strengthen the independence, resilience and capability of Lebanon’s judiciary. This is what I will try to show in this article.

The STL: An Exception or a Gateway to Combating Impunity?

In view of the power and authority that the STL represents, its supporters consider its establishment a major juncture in the process of ending impunity in Lebanon. Yet, regardless of the political framework that guides the work of the STL, three fundamental objections can be raised against such discourse.

The first such objection regards the fact that the crime around which the STL’s activity is mainly focused is that of the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri. Without underestimating the importance or the impact of this crime, setting it apart in such a way raises legitimate questions about the discriminatory aspect of the STL, and thus about the set of values it relies on. Indeed, other crimes have been committed in Lebanon during the same period or even more recently, some of which are much graver from the perspective of international law.

Giving special international importance to a crime committed against a Lebanese political leader to the extent of creating an international precedent, is at its core strikingly reminiscent of the Lebanese amnesty law issued in 1991. The latter had pardoned all war crimes [that took place during Lebanon’s civil war], including crimes against humanity, with the exception of assassinations targeting political or religious leaders. Consisting mostly of such assassinations, the crimes previously referred to the Judicial Council were also excluded from the law.

From this perspective, the STL, like the amnesty law, elevates Lebanon’s political leaders and sets them apart from ordinary citizens. Both effectively consecrate a charisma-based regime -a regime of populist bosses (zu‘ama)- and strengthen its legitimacy. In view of its consequences and of the effective immunity it provides, such a regime in reality represents the main source and cause of impunity. To confirm this, one need only skim through the criminal history of major Lebanese political leaders. One might also look at the rates of constant encroachment on public property, and corruption in the administration of public affairs under the supervision and the protection of these very leaders, which is beyond scope of this article. In this sense, the issue concerns impunity only in cases of assassination of political leaders, even if this were to lead to generalized impunity for crimes committed by such leaders or under their protection.

The second [objection] is that it is somewhat misleading to say that the STL represents a first attempt to put an end to impunity with all preceding crimes having remained outside the scope of prosecution. Trials were conducted in the case of the assassination of political leader Dany Chamoun and his family NS of former Prime Minister Rashid Karami? These were trials for crimes that had been excluded from the amnesty law. Didn’t the Judicial Council issue life sentences for Samir Geagea and his associates at the time? Of course, these trials were instances of selective prosecution. However, so is the STL, as its former head, the late Judge Antonio Cassese himself admitted, pledging nonetheless to guarantee the conditions of a fair trial. If the matter were to be candidly discussed with the then-President of the Judicial Council, Judge Philippe Khairallah, he might well be expected to say the same of Geagea’s trial: that it was selective, but fair.

The inconsistency in the discourse of political forces supporting the STL thus seems very clear. While declaring their ambition to combat political assassinations, these forces have no qualms undermining everything the Lebanese judiciary has achieved in this respect, by ratifying a general amnesty law for Geagea and his associates. Not only is such a comparison useful for assessing the discourse of STL supporters, it also specifically sheds some light on the negative repercussions that could result from the work of the STL for Lebanon’s political system. This can further decrease the likelihood of repeating the same mistakes.

Need one then recall that Geagea’s defenders have successfully imposed the notion in public discourse that his trial was a political one, a trial of the victor over the vanquished, while voiding it of any legal or values-based dimension? Such horrendous crimes, such as the premeditated murder of Dany Chamoun’s wife and their two children, both under the age of 7, thus remained in the margins of public discourse. Meanwhile, the discourse defending Geagea gradually developed from one opposed to the selectivity of his prosecution to one declaring his innocence. By 2005, as his pardon drew nearer, Geagea was being glorified. This process culminated in May 2014, when 48 MPs, most of them supporters of the STL, voted for him during presidential elections.

The prevalence of this kind of discourse is perhaps mainly due to the stance taken by active political forces that had supported Geagea’s trial at the time, when the country was under Syrian tutelage. These forces approached selectivity as proof of their power, and of their ability to subjugate all those who would rebel against them or stand in their way. Meanwhile, they gave no serious thought to the victims of the war, the independence of the judiciary, or the need to combat impunity. If Geagea’s trial succeeded in preventing impunity for specific crimes, the discourse that came with it effectively led to polishing the glorified image of political leaders on both sides, whether they had been imprisoned or not. As mentioned earlier, it also bolstered the charisma-based regime, which constitutes the main source of impunity.

It is unfortunate that the stance taken by STL supporters today is somewhat similar to that of the supporters of the Syrian tutelage at the time. While voiding it almost completely of its legal dimension, both focused on the trial’s political aspect and continued to approach it as a special case, wholly separate from the entire judicial apparatus.

Finally, the third and most important objection concerns the lack of any reform plans for the judiciary in the programs of all political forces, whether they support or oppose the STL. Strengthening the Lebanese judiciary and reinforcing its independence would have represented the main guarantee for combating impunity. One need only consider the exorbitant cost of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. Despite its handling of only a single case, that of the Hariri assassination, the STL’s budget has become nearly double that of the entire Lebanese judiciary. Regardless of the debate over its cost, it would undeniably be impossible to rely on such a tribunal to combat any future crimes. In fact, this enormous cost represents a nearly insurmountable obstacle to initiating trials into the crimes declared connected to the Hariri case: the assassination of George Hawi and the attempted assassinations of Marwan Hamadeh and Elias Murr. Abandoned by the Lebanese judiciary, these cases today seem pending until opportunity that might never come.

What Kind of Independence for the Judiciary?

The sovereignty discourse opposed to the STL faces the same basic problem as the pro-STL discourse. On the one hand, it is connected to a regime of political leaders that encourages impunity, and on the other, it is devoid of any attempt to put forward the Lebanese judiciary as an alternative to the STL or as a national guarantee of justice. To take this reasoning to its logical conclusion would leave one faced with a veritable predicament. Indeed, what could sovereignty advocates say to those who fear an escalation of systematic killings, whatever their source? Should they forget about the protection of the law and seek that of a political force instead? Does that not effectively lead individuals to relinquish their freedom, and consequently society to relinquish its sovereignty, in favor of forces that would impose certain choices in exchange for the protections they provide?

If the pro-STL discourse loses much of its credibility when proven to approach the Hariri case as exceptional and isolated, the anti-STL discourse loses just as much credibility by failing to provide any kind of alternative. Both camps are in fact equally guilty of making the judiciary part of their conflict, instead of keeping it impartial as a guarantee for everyone. In other words, both have turned the judiciary into an extension of the political system, a charisma-based regime of political leaders, when it should be keeping the latter in check.

It would be useful here to remember major milestones that were achieved since 2005, especially as this period witnessed a succession of justice ministers of diverse political orientations.

The Constitutional Council: In 2005, the March 14 camp rushed to issue a law preventing the Constitutional Council from taking any decisions, in view of the fact that its members had been appointed under the Syrian tutelage. In what resembles a purge, this was followed by another law to terminate the service of those members in 2006. The matter was only rectified after the Doha Agreement, when Constitutional Council members were appointed in what resembles power-sharing, without any of them objecting to being described as affiliated to any specific side. During this period, aside from issuing a few decisions about marginal laws, the Constitutional Council seemed to be an extension of the consensual political system instead of keeping it in check. It would be no exaggeration to say that the main feature of this new council was that of refraining to carry out justice. This culminated in some of its members making use of the political maneuver of obstructing the quorum, in accordance with the demands of their political leaderships. This in turn led to passing the law to extend the mandate of the current Members of Parliament.[1]

Special Courts: It can be noted here that both sides [March 8 and March 14] have shown a profound desire to keep special courts exactly as they are. With the exception of a draft law to restrict the powers of the Military Tribunal put forward by MPs from the Lebanese Forces (LF) parliamentary bloc, such courts have since then remained safe from criticism. Drafted by a committee appointed by the Ministry of Justice with the President of the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) as one of its members, and at odds with international trends, a bill to amend the Military Tribunal law even broadened the powers of such courts.[2] The only voice that arose in strong opposition to the Military Tribunal between 2005 and 2014 was that of activist Nour Merheb. He refused to submit to this tribunal or appear before it, rejecting what it represents. In this context, it is quite significant that Merheb eventually put an end to his own life in the context of claiming his freedom.[3] After 2005, even the Judicial Council which had been the symbol of a vindictive judiciary during Geagea’s trial, became a refuge for victims to turn to. Demanding the referral of one’s case to this council became an expression of its importance, amid the broadly favorable outlook of successive governments.[4]

Judicial Courts: In terms of the independence of the judiciary and the principles of a fair trial, judicial courts were no better treated. The country’s active political forces seemed in agreement over keeping the judiciary subjected to a hierarchical structure, thereby facilitating their control over it. This was clearly visible in the power-sharing that characterized the appointment of SJC members, ensuring that political forces would be represented in one way or another within the council. This made the SJC tantamount to a branch of these forces within the judiciary, and at odds with the principle behind its own existence – namely, that of ensuring the judiciary’s independence from these very forces. The latter’s attachment to such power-sharing could also be seen in their persistent disagreement over appointing new SJC members between 2006 and 2008, leading to the obstruction of proposed judicial appointments and transfers for many years. This in turn led to squandering the potential of over a hundred judges, who graduated from the Institute of Judicial Studies (JSI) and waited years before being appointed to judicial positions. The appointment of new judges was also delayed until 2013, making 46 judges wait more than a year before assuming their posts.

This period also witnessed a growing tendency to emphasize the powers of the SJC, strengthening the hierarchical structure and thus the council’s ability to influence the judiciary. This became clear in October 2013, when, for the first time in its history, the SJC applied Article 95 of the law regulating judicial courts. This allowed it to dismiss judges without trial, by a decision issued with a majority of eight of its members. The creation of an SJC Secretariat in April 2014 provides yet another example.[5] Established by decree, the new secretariat was tasked with drawing up regular biannual reports on the judiciary, without the decree including any guarantees or rights for judges regarding such assessments.

On the whole, it can be said that the discourse of holding the judiciary accountable dominated all other judicial reform issues during this period, portraying the judiciary’s problems as stemming from individual behavior. With the political interests they represent, the judiciary’s governing bodies were thus expected to address these problems by activating accountability and assessment procedures. From this perspective, it would be no exaggeration to say that keeping the discourse of accountability and independence separate may well pose a threat greater than the benefit expected of it. Under the present circumstances of rampant favoritism and selectivity, it is more likely to lead to greater vulnerability, inequality and dependency among judges, than it is likely to improve their state of affairs.

In the same vein, almost no attempt was made to strengthen guarantees of the independence of the judiciary or reduce the level of hierarchy. The one exception was a timid attempt by former Justice Minister Chakib Cortbaoui, announced in 2012, which neither reached the Council of Ministers [Lebanon’s executive arm of government] nor was publicly discussed. Not even the official discourse witnessed any progress regarding the principle of electing SJC members, or that of not allowing judges to be transferred without their consent, or even regarding freedom of speech and freedom of association for judges.

As for the financial independence of judges, it had relatively improved at the end of 2011, under the threat of Arab Gulf states luring judges into their employ. However, currently the financial independence is the object of growing restlessness on the part of active political forces that seem unable to stomach it. This was voiced in April and May 2014 by a number of MPs, who questioned the productivity of judges and deemed it inconsistent with their wage increase during parliamentary discussions of pending wage increase plans. The MPs string of statements culminated with the head of the largest pro-STL parliamentary bloc (that of the Future Movement), Fouad Siniora, demanding the reexamination of the wage increase, more than two years after it was ratified. In his view, the decision to increase wages had been made in haste and had not been carefully considered. A number of MPs also supported revoking the social and health care entitlements of the judges’ solidarity fund.

4. Administrative Courts: Here too, there has been no discourse to strengthen the independence of administrative judges. It can thus be noted that no justice minister has made any effort to implement the May 2000 law and set up administrative courts of first instance. Such courts would reduce centralized decision-making and guarantee defendants the right to a two-level trial (i.e. the right to appeal court rulings). More importantly, it can be noted that the government headed by Siniora had explicitly refused to carry out thousands of rulings issued by the council, out of alleged concern for the state treasury, and in total contradiction with the independence of the judiciary.[6]

In conclusion, it can be said that, regardless of their stance on the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, the country’s political forces have on the whole agreed to maintain their hegemony over the judiciary – through special courts and power-sharing in the Constitutional Council and other councils governing the work of the judiciary. The demand of the STL supporters thus seems like a special case, restricted to the Hariri case alone, while the objections of those opposing the STL seem to target justice itself. Their struggle over this issue has led to stripping them both bare, and it is high time for Lebanese society to become aware of this.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.