Social Movements in Tunisia: Fertile Ground but Sterile Seeds?

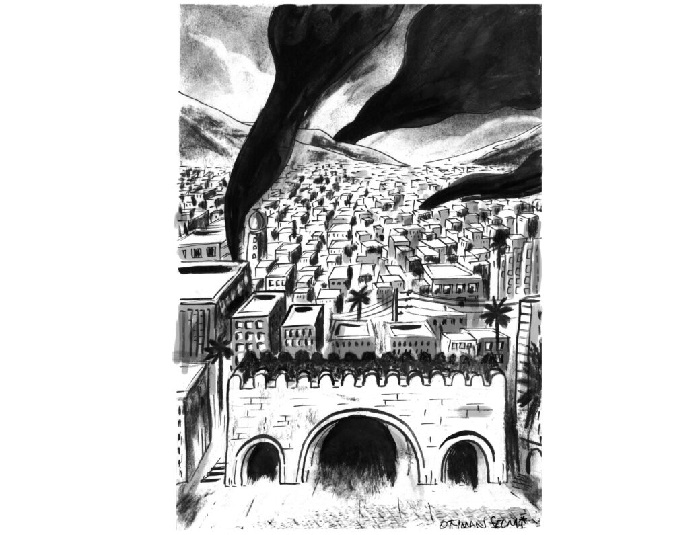

Which of the two dates – December 17 or January 14 – is more important for assessing the revolution? After July 25, is Tunisia witnessing a coup against democracy or restoration of the revolution? Was it really a revolution? These are some of the many questions being asked on the 11th anniversary of the December 2010 uprising. In their midst, the most important question – why did Tunisians rise up in the first place? – becomes lost. Only the social movements continuing for more than a decade remind us of the revolution’s origins and are trying to preserve its spirit and goals.

“Social movements” is one of the most commonly used terms from Tunisia’s post-revolution “lexicon”, particularly in civil society’s discourses and literature. These movements lack a clear or standard definition, but there is an agreement on their main features: they are organized struggles by groups of individuals who are linked by shared conceptions and interests and seek to change certain policies to improve their living conditions. If every movement or action organized by a group of citizens somewhere in Tunisia was counted, we would find thousands. Some lasted mere hours while others lasted months or years. This astonishing number raises an obvious question: Why did most of these protests and movements not bear fruit? Why did this surge not affect the general public’s lived reality?

While there are no definitive answers, this article will explore the structural and essential obstacles affecting the fertility of the seeds that are these social movements. Because of their multitude, diversity, and varied demands, I have selected four categories of movements to analyze based on their importance or frequency.

Movements Defending the Right to Water

In 2020, WatchWater received 1,345 citizen reports about water problems such as long outages without notice, continuous deprivation from water fit for drinking or irrigation, and leaks lasting longer than three days.[1] This figure reflects only the cases reported to the aforementioned observatory. Recent years have also witnessed increasing warnings by governmental and research bodies about worsening water resource scarcity in Tunisia. Since 2015, there have been successive hikes in the pricing of water for household consumption. Tunisians’ consumption of mineral water has also doubled in recent years such that Tunisia now ranks fourth globally (225 liters per capita in 2020),[2] amidst frequent outages and a decline in the quality of the water provided by the National Water Distribution Utility (SONEDE). In recent years, several movements protesting water pollution and/or depletion have occurred. These movements include those against the Gafsa Phosphate Company in the mining basin, the chemical plant in Gabes, the mineral water-bottling plants in Kairouan, and the quarry in the town of Houaidia, Jendouba Governorate.

Movements by People Affected by Garbage Dumps

The household waste collection crisis occurring in the city of Sfax since the resurgence of the social movement demanding that the Qunna Garbage Dump in Agareb Delegation be shut down is not the first for Tunisia, nor will it be the last. Despite all the government discourse about recycling waste and improving the dumps,[3] Tunisia seems effectively unable to dispose of its waste. Eleven supervised dumps and multiple more informal ones receive 2 to 3 million tons of waste each year. They have become a chronic headache in several parts of the country, not only because of their locations but also because they have surpassed their operational lifespan and they emit harmful fumes and gasses as the authorities mainly bury the waste. Since 2011, protests against these dumps have continued practically uninterrupted in Djerba (the Telbet/Sedouikech dump), Monastir (Gazzah dump), Sousse (the Bouficha dump), Nabeul (Menzel Bouzelfa, the Errahma dump), Gafsa (the municipal dump in Sidi Ahmed Zarroug), Kairouan (the Batin dump), Tunis (the Burj Shakir dump), Sfax (the Qunna dump and the Ein Flat/Thyna dump), and other areas.

Movements Targeting Extractive Businesses

Prolonged, organized protests have occurred around and inside facilities and businesses operating in the sectors of oil and gas (Kamour/Tataouine, Skhira and Kerkennah/Sfax), phosphate (Gafsa), chemical industries (Gabes and Sfax), and plaster (Tataouine). These movements primarily sought employment, contributions to regional development, and a reduction in environmental damage. They are more notable than the other movements because of their continuity and “intensity”, as well as the economic weight of extractive activities.

Movements to Reclaim State Lands

In the first months and years following January 2011, citizens seized approximately 70,000 hectares of unexploited state-owned lands[4] or tried to take control of agricultural revival companies (farms that the state owns and leases to private investors) in various parts of the country, particularly its western region. Most of these movements were carried out by individuals or families. However, a few were conscious collective actions aimed at exploiting agricultural lands in a manner that guarantees workers’ rights, avoids depleting the land, and allocates the surplus profit to regional development. Primarily, these cases include Tarfaya in Zaafrane and Hanshir al-Muammar in Jemna (Kebili Governorate), Hanshir Ben Arar in Dahmani (Kef Governorate), and the Umran and Itizaz farms in Menzel Bouzaiane (Sidi Bouzid Governorate). Some lasted mere days, while others have achieved years of ongoing success.

Dividing Causes

One of the most important and deep-rooted reasons for the ineffectiveness of Tunisia’s social movements is that they separate cause from effect and attempt to treat the symptoms without addressing the underlying ailment.

Water inequality cannot be addressed through the construction of a few sporadic channels and the publishing of ads raising awareness about the need to rationalize water consumption. The issue runs much deeper and is connected to the political administration of Tunisia’s water resources. Despite all the discourse about the risk of thirst in Tunisia, based on water poverty and water wealth defined by international organizations in accordance with liberal visions, Tunisia is facing a risk of depletion not drought. Decades ago, the Tunisian state chose to farm intensively and to mobilize as many water resources as possible to develop an agricultural industry based on intensive irrigation and export-oriented production. More than 80% of water resources mobilized in Tunisia go to agriculture, not to achieve food sovereignty but for the sake of exporting top quality products and earning the hard currency needed to import grain, vegetable oils, and other goods. For many years, SONEDE has suffered the consequences of austerity policies and water commodification. In 2008, the state ended its support, leaving the company to rely on its own resources – i.e. consumer bills – to maintain a network of depreciating channels and plants that leak enormous volumes of water, not to mention the deficit in new projects.

In short, the water problems stem primarily from mismanagement and policies that serve investors instead of users. Water protests and social movements may compel the state to construct a few channels here and there, but given the continuation of the same policies, nothing guarantees that they will carry enough water or that the water will be fit for human or plant consumption.

In theory, at least, the garbage dumps issue is less complex than the others. The solutions are primarily technical and involve awareness-raising. However, the problem once again lies in the state’s policies and choices: Why force the construction of a landfill beside a residential area or on agricultural land? How long will the policy of burying waste, instead of sorting it, reducing its toxins and emissions, and using as much of it as possible in manufacturing, continue? When will participatory policies that grant citizens a role in administering this matter be adopted? What about the role of the municipalities, particularly now that the decentralization law has been adopted? There is also what we could call the “waste economy”: Private companies contracted to collect and transport waste are at the top. In the middle, small companies and plants that recycle plastic and metal compete, while the crowded bottom is filled with are armies of waste pickers working in degrading and risky conditions to support thousands of families. Before any talk about civic consciousness, its most basic condition – small and large bins dedicated to each category of waste in every area – must be met.

Regarding the issue of extractive companies and their social responsibility, hiring a few people after each string of protests and clashes (which sometimes result in deaths) cannot be an effective or permanent solution. After the protests, companies can fire workers and reassign others. Now and then, they also spend a few thousand dinars on sports associations or educational institutions in the area and exploit them for good publicity. Meanwhile, they continue to exploit natural resources as cheaply as possible and pollute the ground, air, and water table. While it is essential that extractive businesses provide employment and contribute to development, these matters should not come in the form of charity. Rather, the minimum number of jobs to be earmarked for locals, the percentage of profits to be spent on developing the region, the polluter-pays principle, the water footprint, and means of preparing the region for the end of extractive and manufacturing activities should all be codified in laws and exploitation contracts.

The seizure of state lands is a more complex issue. These lands are the result of more than five centuries of national rulers who seized and plundered the inhabitants, particularly tribes people. This policy began when the Ottoman beys took control of the Tunisian “province” in the 16th century and intensified in the era of French colonialism (1881-1956). Both the post-independence state and the 2011 revolution tread the same path. These lands totaled approximately 800,000 hectares after the religious endowments system was abolished in 1957 and the last lands were recovered from the Europeans following the agricultural decolonization of 1964.[5] Their original owners hoped that the end of colonialism would restore their rights, but instead the lands became state-owned and a testing ground for the regime’s policies. Sometimes they were a model for socialist “cooperatives” to emulate (1964-1969),[6] sometimes they were an experimental platform for economic openness and liberalizing the agricultural sector (after Hedi Amara Nouira became prime minister in 1970), and sometimes they were a means of attracting private investors and clientelism.

We cannot confirm whether the successive seizures of state lands in the months following January 2011 were legitimate or whether the people involved were well-intentioned. However, it is clear that most of the lands seized were primarily agricultural and the people involved were locals, primarily unemployed people and small farmers. The seizures did not last long as most lands were recovered by the state “peacefully” or through law enforcement beginning in 2015. Even Jemna Oasis, which after 2011 constituted a unique example of self-administration of an agricultural resource, legally belongs to the state and is merely rented by the Association for the Protection of Jemna’s Oasis. Its only accomplishment is escaping intensive and greedy capitalist exploitation such that its revenue is divided among the workers and used to develop the oasis’ surrounding area. There is an army of small farmers who own little to no land while hundreds of thousands of hectares remain completely or partially unexploited. And however common individual attempts to seize these lands may be, they will not triumph against the machine of the state nor convince the public, which will see them as attempts to plunder public property. The greatest difficulty remains convincing small farmers of the importance of agricultural reform to begin with. For example, the Brazilian Landless Workers’ Movement waged decades of struggles, lost hundreds of members seizing lands, and was offering a comprehensive project that combined eradicating illiteracy, politically educating farmers, and devising means of collective exploitation that guarantee farmers food self-sufficiency and sovereignty irrespective of the market.

Sparse Islands in One Desert

According to the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights, mass protests numbered around 8,760 in 2020, 9,090 in 2019, 9,356 in 2018, 10,450 in 2017, and 8,710 in 2016.[7] There have been thousands of protest movements every year in almost every area for more than a decade. Most movements make similar demands (such as employment, development, health, drinking water, and alleviating environmental damage). Yet – as though oceans separate them – they do not intersect or coordinate with each other, even though a minimum level of freedom of expression, organization, and movement is available and means of communication and rapid coordination have been developed. This dispersion allows the authorities to easily single each movement out and gradually absorb it.

The Same Ineffective “Magic” Formulas

One reason that the social movements are ineffective is that they adopt basically the same tactics and means of struggle, as though they are suitable for every time and place. The means consist of protests in front of economic establishments or governmental offices, blocking traffic, strikes, and marches that end in clashes with security forces or disappointed and irritated protesters. Many Tunisians do not yet comprehend that the window for revolution ended with the legislative and presidential elections in 2014, whose results stabilized the system and state. Even with the exigencies of “democracy”, the authorities had no trouble breaking up most protests and social movements in recent years, alternating between ignoring, stalling, inciting public opinion against the protesters, containment, staging and prolonging their implementation of demands, and violent and occasionally lethal repression.

Social Movements with No Left?

The social movements are missing or short on one essential ingredient needed to mature and bear fruit: the left.

Since 2011, the Tunisian left has been facing a deep existential crisis. It had to transition from struggling against dictatorship to actually meeting the “masses” without any barriers. It also had to choose between opposition and participation in government, between revolution and compliance with the rules of the “democratic game”, and between socioeconomic rights and individual freedoms. From the outset, part of the left engaged in the “democratic transition” process and opted to “build constitutional institutions” and “consolidate the democratic experience” with old regime figures and then Islamists. The other part, the so-called “radical” left, leaned more toward the socioeconomic rights demanded by the December 2010/January 2011 uprising and dissolving the dictatorial legacy. But with the recurring terrorist attacks, violence by militias close to the Islamists, and political assassinations, the “radical” left’s compass gradually turned, and its social spirit faded. It began to focus more on issues of individual freedoms and democracy and entered alliances with “modernist” right-wing forces to counter Ennahda. This choice damaged its credibility and deepened the gulf between it and the popular classes.

Professional Activists

Given the weak presence of leftist forces in the dynamics of these social movements and the limited support it provided them, a supposed alternative called civil society components comes to the fore. Rights organizations and observatories play a significant role in monitoring violations against protesters, raising awareness of their causes and activities, and logging and mapping protests and social movements. While these roles are important and commendable, they cannot fill the gap left by the absence of political movements with inclusive and collective projects. There are fundamental obstacles that prevent civil society components, even the most active and credible ones, from being the missing ingredient that Tunisian social movements need. With a few exceptions, they suffer from the same flaw that mars these movements: they fragment socioeconomic causes, decontextualize them, and fear politicizing them. Generally speaking, civil society components are, in definition, law, and practice, specialized in specific issues or concerns. Even the most “radical” ones have reformist goals and calculate their discourse and actions carefully to avoid accusations of politicization, partisanship, or “bias”. Likewise, civil society activities depend largely on external funding, both domestic and foreign. This funding does not necessarily prevent independent decision-making, but it often constitutes an inlet for agendas that do not necessarily match Tunisians’ priorities and situation. These entities also create a generation of “professional” and specialized activists most of whom work on only one issue or problem and master only one function.

Conclusion

This analysis of the ineffectiveness of Tunisian social movements and the obstacles to their development does not derogate from them or their struggles. Most social movements occur in peripheral regions, where the presence of parties, unions, and civil activists is weak and the mass media only ventures in rare cases. Consequently, it is difficult to secure support from party and civil forces and public sympathy.

Given the decline of party and ideological forces struggling against neoliberal policies, social movements remain essential for slowing the machine crushing socioeconomic rights. These movements are also helping to build pressure, develop experience, demands, and means of action, and keep the embers of citizenship and dignity burning until they can break free of their geographical and ideological confines and broaden their horizons.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] Map of Thirst for 2020, WatchWater.

[2] “Istihlak al-Miyah al-Mi’daniyya fi Tunis, al-Waqi’ wa-Tahaddiyat”, WatchWater, July 2021.

[3] See the national strategy for waste disposal developed by the National Waste Disposal Agency.

[4] See Tunis Afrique Presse’s interview with Mabrouk Korchid.

[5] Mohamed Elloumi, “Les terres domaniales en Tunisie”, Études Rurales, is. 192, 2013, p. 43-60.

[6] Ibid., and Werner K. Ruf, “Le socialisme tunisien: conséquences d’une expérience avortée”, Introduction à L’Afrique Du Nord Contemporaine, p. 399-411.

[7] See the reports by the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights for 2018, 2019, and 2020.