Seismologist on Lebanon’s Dams: Listen to the Experts

The 7.8-magnitude earthquake that struck southeastern Turkey on 6 February 2023, affected broad parts of northern and western Syria, and reached Lebanon with a magnitude of 4.8. Amidst the rescues and rubble-clearing, a debate – part scientific and part speculative – rages over whether the Turkish dams are behind the Anatolian fault’s movement and the subsequent seismic disasters and human tragedies. As of Saturday 18 February 2023, the death toll from the earthquake has exceeded 46,000, not including the missing.

Amidst this discussion, videos were published about Turkey beginning to empty some dams, including the Sultansuyu Dam. Turkish Vice President Fuat Oktay confirmed this news and said that the dozens of other dams in the country are not in danger. The gradual emptying of some Turkish dams was sometimes justified on the basis that they might collapse in the earthquake’s aftershocks. However, some wondered whether the goal was to reduce the weight of their reservoirs on the strata, in reference to the impact of some human activities on earthquake activity. In Adana (southern Turkey) following the earthquake, the Turkish minister of agriculture and forestry denied that dams were being emptied. He said that the quake-affected regions include 110 dams and 30 lakes and that “there is no threat to safety in our water facilities”, i.e. there is no fear that they will be affected by aftershocks.

In support of the theory that dams affect earthquakes, Christian Klose (from NorthWest Research Associates) has spoken in a video report about Hoover Dam in America, which is considered a symbol of American engineering genius. The dam was built in 1936 on the Colorado River to generate electricity and help irrigate the country’s southwest. The report says that, “Before the dam was built in the 1930s, this area on the border of Arizona and Nevada had no known history of quakes. But as Lake Mead began to fill, that began to change… seismic activity increased over time and several hundreds of small earthquakes were induced in the vicinity of this reservoir”. It concludes, “Today, the level of quakes fluctuates in direct response to the water level. More water, more quakes”.

We Must Study Earthquake Activity Before and After Dams

In an interview with the Legal Agenda about Lebanon’s planned dams, seismologist at the American University of Beirut Tony Nemer declines to say with certainty that Turkey’s dams are connected to the February 6 earthquake: “They may be connected. But we cannot say for sure or answer lightly before studying the activity of the seismic faults, particularly before and after the dams’ construction”. He says that in media interviews, he has alerted Turkish authorities to “the danger of emptying the large dams today after the quake, if they intend to do so. If the dams are connected to seismic activity, emptying them will have adverse consequences”. He explains, “The quake vented pressures in the ground as it repositioned into its natural state. Any drainage of the dams’ water will leak into the seismic faults, again changing the underground pressures. Hence, it would inevitably cause adverse reactions as the ground has become accustomed to the dams’ presence”. He stresses, “We can’t mess around with dams. We are talking about large quantities of water, about tremendous active seismic faults. Unfortunately, we’ve seen the cost of their movement”.

Turning Fear into Knowledge

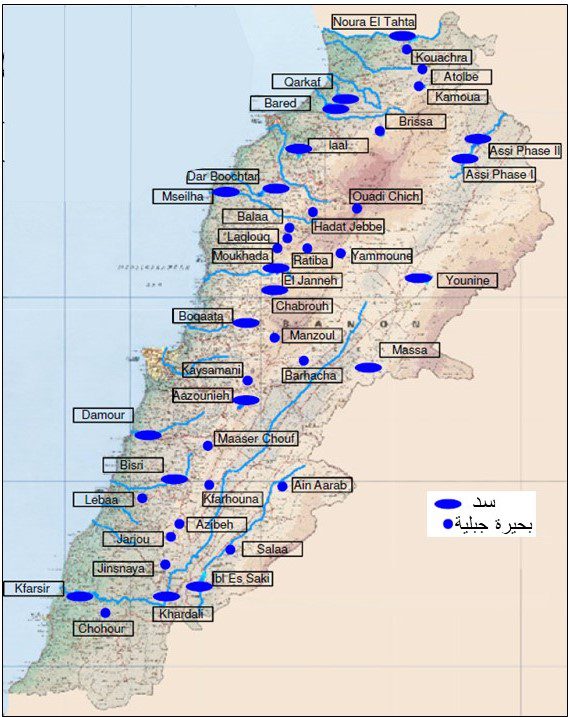

The consequences of the Turkish earthquake reopened the already-heated debate in Lebanon about the plan to construct 27 dams and lakes issued in 2000.[1] A battle was previously waged to stop the Bisri Dam project for various reasons, including scientific debate bolstered by Nemer’s study published in Engineering Geology and summarized in the Legal Agenda’s special issue about Marj Bisri. The study demonstrated that the Bisri Dam could risk triggering seismic faults because of the presence of the Roum and Basri faults in the Marj Bisri region, where the dam was planned. Nemer supported this study with a second one published later, and he is finalizing a third in preparation for publication.

To cast more light on the composition and features of Lebanon’s ground strata and illuminate the scientific reality of the country’s seismic faults and the extent to which they affect or are affected by dams, Nemer says that there is a need to “turn fear into knowledge, terror into prevention, and panic into coexistence with reality… The danger exists as long as the causes [i.e. the movement of the plates] exist”.

In his interview with the Legal Agenda, Nemer hopes that “the Turkish earthquake rings alarm bells for us as a people so that we know and are conscious of where we live and what we have around us, not for fear and terror but so that we realize we are in a seismic region, take precautions, and do what we must”. He hopes that politicians have learned the lesson that “contempt for science and scientific talent can put us in a predicament and destroy the country more than they destroyed it economically”. He calls on officials to “listen to scientific opinions and not deem them politicized or paid for by embassies”.

Regarding those who made the decisions to construct the dam projects, Nemer asks, “Weren’t they terrified when the earthquake struck? Didn’t they fear for their children, if not the general public? Did they think about the possibility of the same thing happening to us because of their decisions, even if it’s 1%?” He implores them to “stand in front of the mirror and self-reflect” and to “correct their error, as going back on a mistake is a virtue”.

Dam Construction: Science Before Politics

Before delving into Lebanon’s geology, Nemer confirms that he is not against dams “if they are studied in a scientific, transparent, careful, and credible manner and not implemented for political reasons far removed from science and what it says”. He cites Norway as an example: “The Norwegians produce 98% of their electrical needs from hydroelectricity via dams. But they know what they’re doing and how to do it as they have conducted careful scientific studies and respect the environment, without threatening their country or people”. In Lebanon, “We lack careful scientific studies and don’t listen to experts except those who are surrounded by the politicians themselves and merely agree to whatever is asked of them”.

Nemer talks in general about the features of Lebanon’s geological composition. On one hand, 80% of Lebanon’s mountains are karst, which is known for absorbing precipitation and storing it underground, not on the surface. On the other hand, Lebanon lies on seismic faults.

He elaborates that Lebanon lies on the Dead Sea Transform, a fault line that extends from the Gulf of Aqaba to southern Turkey, passing through Araba Valley between Palestine and Jordan and then the Dead Sea in the Jordan Valley. When it reaches Lebanon, it splits into four branches: the Yammouneh fault (the main branch), the Roum fault to the west, and the Rachaya and Serghaya faults.

Nemer mentions that the “bending” of the Dead Sea fault millions of years ago is behind the formation of Lebanon, its eastern and western mountain ranges, and the Beqaa plain that stretches between them. He continues, “The bend contributed to the separation of the Dead Sea fault in Lebanon into a main branch, known as the Yammouneh fault, which extends along Lebanese territory, a westward branch known as the Roum fault, which is approximately 35 km long and ends in the Bisri Valley, and two eastward branches: the Rachaya fault, which is 40 km long and ends in the direction of Yanta in far-eastern Beqaa, and the Serghaya fault, which extends approximately 80 km to southern Qaa and northern Beqaa”.

Nemer returns to the Lebanese dam experience, which has proven to be a failure as the people in power flout all scientific studies, approaches, and principles. As one example, he mentions the already-constructed Mseilha Dam and asks, “Is it a model to be proud of?”

The Bisri Dam Will Definitely Trigger the Roum Fault

In a special issue titled “Marj Bisri at the Heart of the Uprising”, the Legal Agenda included a summary of Nemer’s study published in Engineering Geology. The study warned of the catastrophic seismic risks of implementing the Bisri Dam project. It cited the region’s geology, which is not fit for the dam’s construction. The Roum and Bisri faults have a history of movement, and the region was devastated by an earthquake in 1956. Nemer repeats that constructing the Bisri Dam would be dangerous and could cause reservoir-induced seismicity. If it triggered the Roum fault, the ramifications of the earthquakes would be impossible to predict or address and would threaten all of Lebanon. He stresses the need to reconsider the dam’s location and listen to what objective scientific studies say about the geological structures, the nature of the ground, and the activity of the faults: “The studies are now within reach of those in power and in the public’s hands, so any flimsy arguments about not knowing the consequences are invalid”.

When the Legal Agenda asks about the risk level of the Bisri Dam and whether it would trigger earthquakes if constructed, Nemer responds definitively: “Scientifically, the risk is 1000% – the dam will inevitably trigger quakes”. He then stresses, “We’re not sitting idly, nor are we theorizing in the abstract. All our data is based on scientific foundations. We conducted and published two scientific studies about Bisri, and we’re in the process of publishing the third. They all confirm what we already know, 1000%, the situation is undebatable, Bisri Dam will trigger tremors. Once the tremors begin, even if they are initially mild, nobody knows how things might develop”. He continues, “At that point, the situation is impossible to control”.

Janna Dam Scorched the Region

Millions of dollars were squandered on the construction of the Janna Dam before the current financial crisis halted it. These works devastated and deformed the mountains and forests of Nahr Ibrahim Valley, which is one of Lebanon’s most important valleys because of its biological richness and biodiversity. Nemer describes the horrific extent of the environmental destruction. When he visited the Janna region, he felt as if he had entered “the site of a destructive crusher”. He explains that the environment in Qartaba indicates that the region is young: “Erosion factors have not yet stopped, so the region is still forming and hence the faults there are still active”.

When we ask about the concerns over the dam’s impact on the three seismic faults underneath it, which we previously raised in our investigation of the project, Nemer says, “The area is seismically active as the faults are moving”. He stresses that dams should not be placed near the faults: “A tectonically, seismically active area is not fit or suitable for dam construction”.

The Mseilha Dam: A Legendary Failure

Nemer describes the Mseilha Dam as a “legendary failure”. The works wreaked havoc in the area, and they are still trying to patch and repair the defects they encountered. He says that, “Even if they pave and cement its floor and manage to collect water in it, the question is, where will they draw this water? And the dam is 45 meters above sea level, which means weak gravity, sediment accumulation behind the dam, and expensive pumping. It was also constructed alongside the Batroun fault and its fragile geological floor, as evidenced by the landslides in its vicinity, the latest being the mountain collapse just before the Chekka tunnel”.

He recalls that the goal of the dam is to irrigate Batroun’s villages, all of which are located above the dam, so expensive pumps will have to be installed. This conflicts with the principle of building dams in a manner that takes advantage of gravity.

Nemer strongly condemns the flaunting of the dam’s lake as a tourist development in Batroun at the expense of more public squandering and debt, not to mention the destruction of the region. He wonders, “Does it make sense to waste over USD70 million [the acknowledged cost] on kayaking on a lake? And so close – nay adjacent – to the distinctive Mediterranean Sea?”

When asked about the dam’s effect on seismic faults, Nemer relays the conclusion he reached in a soon-to-be-published study on Bisri that addresses the Mseilha Dam: “It might activate the Batroun fault and impact its seismic activity, but the main problem lies in its location and on the structural level”.

Nemer says that he is in the process of completing studies on the Balaa Dam, the Boqaata Dam, the Janna Dam (in detail), and Brissa Dam. “As for Yammouneh and Qaysamani”, he adds, “they are more like mountain lakes. Yammouneh already existed naturally, while Qaysamani is like a dish of water”.

Brissa Exists to Enrich the People Involved

Nemer criticizes the construction of the Brissa Dam at the top of the mountain, specifically near the beginning of the descent from Hermel’s jords [barren hinterlands] toward Sir el-Denniyeh and no more than four or five hundred meters from the watershed. Consequently, it lacks sufficient geographical span to be filled by precipitation in the area. Moreover, because every dam leaks a certain percentage of its water, the water that can be collected in Brissa will leak out. Hence, he concludes that the dam seems like a project devised to enrich the people involved. He does not comment on the nature of the dam’s ground, which is said not to store water, because he has not yet studied it. The Legal Agenda published an article about the Brissa Dam following Parliament’s legislative session on 24 September 2019, in which MPs raucously debated a request for additional funds to complete the project, which was going to cost almost 3.5 times the original price of approximately USD10 million. While the Financial Public Prosecution later filed charges against the Council for Development and Reconstruction with Acting First Investing Judge in Beirut Charbel Abou Samra, the case is still pending.

Boqaata Caused Keftay to Slide

Nemer says that efforts by the builders of the Boqaata Dam to expand its pond caused the adjacent village of Keftay to slide: “They shoveled at the edge of the river, and the whole village began sliding because the ground is sandy. They knew the ground is sandy and doesn’t even hold water. Now they are pouring concrete and asphalting it”. He says that a seismic fault passes by the dam, “But I haven’t studied it yet, and I can’t say for sure whether the dam will impact its activity”.

Balaa Is Illogical

Nemer begins his discussion of the Balaa Dam with the dozens of mountain lakes that locals dug and constructed decades ago, which “are environmentally friendly, collect their water needs, and increase water without destroying nature or costing enormous amounts”. The lakes also “add aesthetic and tourist appeal to the region and do not deform it like the dam”, as the Legal Agenda showed in its special investigation of the dam.

He addresses the name of the region: “Balaa means the region of sinkholes [balawi’]. It is home to the Baatara sinkhole, which people know as the Balaa sinkhole. This is a region of sinkholes, and it is illogical to build a dam there”. He moves on to the size of the dam’s lake: “Its maximum capacity is 1.5 million cubic meters – a bucket of water. They should have developed the region for tourism by exploiting its dense underground caves and linking them together. Also, its sinkholes are connected beneath the dam’s floor and could be exploited with spelunkers. These are possibilities that I don’t know exist in Europe or South America”. Instead, “They spent enormous amounts on the cost and the concrete with which they tried to seal the sinkholes in the body of a lake that, if they succeed, will hold no more than 1.5 million cubic meters of water. But the focus is clearly not on utility but on the dams themselves”. He concludes, “I feel like someone passes through any area, gestures into the air, and tells them, ‘Make me a dam here’, and nobody says no”.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] The plan was approved by the Council of Ministers via several decisions (Decision no. 14/1999, Decision no. 12/2000, Decision no. 18/2003, and Decision no. 3/2003), and Parliament authorized the ministry to implement it in 2003.