“Professional Ethics” Decision Threaten Lawyers’ Freedoms and Rights Advocacy

On 3 March 2023, the council of the Beirut Bar Association decided to amend certain provisions of lawyers’ code of ethics. These amendments restrict lawyers’ freedom in an unprecedented manner that exacerbates the restrictions the same council imposed on 3 March 2011, exactly 12 years earlier. While the 2011 council endeavored to largely restrict lawyers’ freedom to discuss cases pending before the judiciary, the latest decision goes as far as to restrict their freedom to participate in public legal debates while leaving them with complete freedom to discuss political issues, cultural issues, sports issues, and so on. Not yet satisfied, the council also restricted lawyers’ freedom to criticize the Bar Association’s president and council members and their colleagues, especially during elections.

The council made this decision suddenly and without any prior discussion or consultation with lawyers individually or via their general assembly, as is supposed to occur when the subject is professional ethics. The decision endorsed an approach that sought prohibition and prior censorship without providing any justification or rationale, or citing any intellectual work about how lawyers may exercise freedom of expression. Hence, lawyers seeking to understand the decision’s justifications had to track the statements by the president and some council members in the media. These justifications were conflicting, and some seemed to be nonsequiturs (e.g. the justification of restricting lawyers’ freedom to appear in the media on the basis that some lawyers have participated in storming public departments). Moreover, the decision’s content was kept under wraps for approximately two weeks, only to be leaked on March 17 and rapidly published in an ethics booklet in an effort to make it a fait accompli. As soon as these decisions were announced, they were widely rejected by a large swathe of lawyers, especially activist lawyers, who have played an integral role in rights, reform, and protest discourse since the garbage-crisis protests in 2015 and especially after 17 October 2019.

Subsequently, 16 lawyers, including the author of this article, filed challenges to this decision on the basis that it both impinges on their freedom and strips them of one of their most important weapons for advocating social causes. It does this amidst harsh social conditions that warrant encouraging and preserving this role more than ever before.

This article will explain the content of the decision, its dangers, and the main arguments made by the Bar Association and its opponents. This it will do in three sections, each one dedicated to one of the ends of the restrictions imposed.

Trial Publicity in Pitch Darkness

The Beirut Bar Association first began restricting lawyers’ freedom in 2011 by categorically prohibiting them from discussing cases pending before the judiciary in the media and telecommunications. This ban covers not only lawyers’ own cases but all cases, including those in which their colleagues are working. While the council exempted major cases from the ban, it made discussing them contingent on prior approval by the Bar Association president. By declining to define “major cases”, the council enabled the president to impose his own definition while exercising his prior censorship. The then-nascent Legal Agenda published an article criticizing the approach in an effort to deter the association from adopting it. We also explained our reasons for disagreeing with the Bar Association’s council in this regard. Instead of reducing the restrictions on freedom, the council eventually, with its 2023 amendments, expanded this ban in two important ways. Firstly, the ban now includes discussing pending cases not only in the media but also on social media, websites, pages, and any kind of online network. Secondly, it now includes the publication of pending investigations or casefiles.

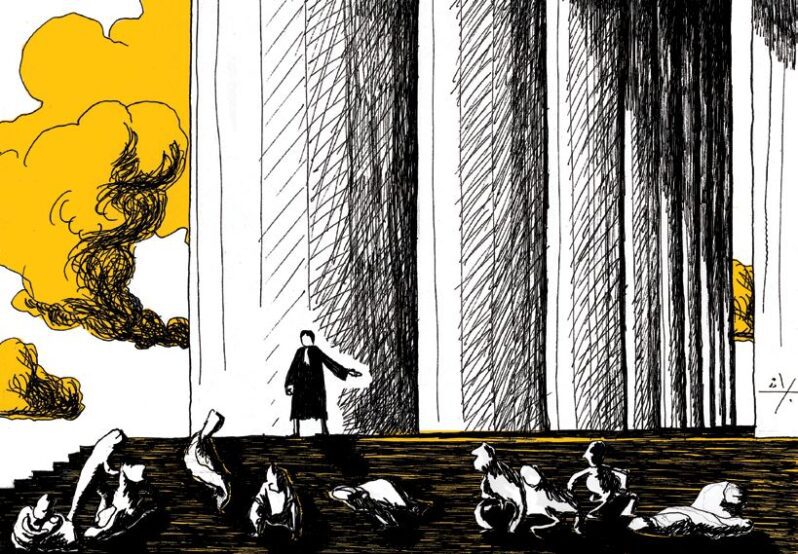

In effect, it seems the ethics code adopted in 2011 and 2023 seeks to strip lawyers of any ability to appeal to public opinion, contribute to the formation of public opinion on pending cases, or even participate in any public debate about them, in addition to stripping them of the freedom to publish the facts of these cases even without commentary. In other words, it derogates not only from lawyers’ freedom but also from their ability to perform their duty of advocating any such case, whether they are representing one of its parties or merely supporting it. Making matters worse, the decision was issued under social circumstances in which broad segments of the population are suffering many injustices that they cannot stop because of the continuous interference in the judiciary, the widespread bullying of any judge who dares prosecute any influential party in the media, and the near-total obstruction of key investigations through the tactic of suing the judges, which the Independence of the Judiciary Coalition has mentioned in several statements. Moreover, disinformation usually awaits any judicial move toward exposing corruption. What are lawyers in such cases expected to do? Should they remain silent? Practice self-pity? Or should they fight fiercely using their knowledge of the law and what goes on behind the scenes in the judiciary to advocate their cases and set the facts straight in the face of disinformation? If the answer to this question is obvious, then so is the Bar Association council’s infringement on lawyers’ freedom and role.

Of course, the association could have strived to solidify lawyers’ knowledge of – and commitment to – professional ethical rules that bar the exercise of illegitimate pressure on the judiciary or misuse of the media. But by resorting exclusively to a comprehensive ban and prior censorship with no controls, it far exceeded the principles of necessity and proportionality, and put its decisions at complete odds with the constitutionally and internationally guaranteed principles of freedom of expression.

Impoverishing and Containing Public Legal Debate

As previously explained, in 2023 the Bar Association’s council not only restricted lawyers’ freedom to discuss cases pending before the judiciary but also rushed to subject their freedom to participate in conferences and media interviews to prior censorship by the association’s president. Hence, the council transformed lawyers’ freedoms in this realm from ones guaranteed by the Constitution and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights into ones controlled by the Bar Association president. Making this violation worse, the decision placed no controls on the exercise of this censorship, e.g. by defining the mechanism for submitting permission requests, the timeframe for granting or withholding permission, the criteria upon which the president’s decision might be based, or the mechanism for challenging the decision. Evidentially, this prior censorship is absolute, open to all kinds of discretion, and subject to no accountability. The president can make decisions based on predominantly personal considerations, indulging whomever he pleases and imposing a disguised punishment without any trial on whomever he chooses. He can also favor certain legal views by allowing them to appear in the media while preventing opposing views from doing so.

In effect, this not only restricts lawyers’ freedom to discuss matters within their expertise but also impoverishes public legal debate, threatens rights-based and protest discourse, and denies society access to their legal knowledge at a time when it desperately needs such knowledge. Access to this knowledge is especially important because of the political authorities’ failure to present any solutions to the escalating living, financial, and economic crisis and the prioritization of group interests over public interest, including via preparations to sell state assets for the benefit of the banks and major depositors. What might lawyers do in such a crisis? Do they remain silent or – to the contrary – do their utmost to correct public debate and construct a public opinion that supports the necessary reforms and opposes plans and schemes that could further destroy society? Does it make sense for law experts to be subject to prior censorship while allowing people who do not know the law, or at least lack expertise in it, to be platformed without censorship or controls? What is the point of subjecting lawyers’ appearances in their area of expertise to prior censorship, while leaving them free to discuss matters outside their expertise? This can only be understood as an attempt to silence those who know or to contain and steer public legal debates while society is waging legal battles, some of which are extremely important to its present condition and future. In this regard, it suffices to recall the role played by lawyers, including lawyers from the Legal Agenda, the Bar Association’s own Committee for Defending Depositors, and depositors’ unions, in the battle for the law to lift banking secrecy and the battles over the financial laws currently proposed.

Additionally, the Bar Association president’s prized new authority could backfire on him. He could be held responsible for the statements of any lawyer who has obtained his permission to appear in the media, at least whenever he had information indicating the direction they would go. Hence, we fear that the Bar Association president will find himself in an unenviable position between the hammer of lawyers yearning to exercise their freedom and perform their role and the anvil of the influential forces aggrieved by this freedom. Either he indulges the lawyers and is attacked by these forces and ultimately held legally – or at least politically – responsible for not restraining their freedom, or he indulges these forces and becomes a tool for repressing lawyers on their behalf. The latter, too, could expose him to many criticisms and prosecutions, sooner or later giving him a reputation of acting as a censor or anti-freedom police.

A Bar Association Above Accountability

Finally, the decision also amends Article 41 of the ethics code to prohibit directing injurious remarks at the Bar Association’s president and council members and other lawyers, especially during the association’s elections. This prohibition appears to prevent a lawyer from criticizing any colleague, not only for professional matters but also for any public affair, including – for example – potential involvement in corruption, interference in the judiciary, or environmental and financial crimes. A lawyer must refrain from any criticism of colleagues, including their professional track records, even if they have nominated themselves to represent lawyers in the Bar Association’s council and control several aspects of lawyers’ careers. Here, the Bar Association’s council appears to be using its authority to shield its image and the image of its members. This prevents the publication of any facts about them, even in elections, wherein candidates are supposed to present themselves truthfully and representation should not be decided on the basis of equivocation, deception, or concealment. This prohibition also restricts freedom in an arbitrary and unjustified manner, especially as it too is comprehensive and devoid of any criteria, controls, or exceptions.

The Bar Association was expected to intervene to prevent lawyers from engaging in interference in the judiciary and using illegitimate methods to perform their duties, and by doing so, deny them an illegitimate competitive advantage against lawyers who reject such methods and undermine justice. By intervening to prevent criticism of any lawyer, however disgraceful their actions may be, we fear that the Bar Association is enforcing silence about illegitimate methods and bolstering and increasing them, along with illegitimate competition. In practice, such a measure also limits lawyers’ ability to expose corruption in contravention of Article 13 of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, which obliges the state and all its institutions (implicitly including professional syndicates established by laws) to encourage social forces to expose corruption, not place restrictions on such exposure.