Lebanon: Ministry of Labor Delays Adopting an Aborted Reform

In a press conference on 10 December 2021, while defending his November 25 decision regulating foreign labor in Lebanon (Decision no. 1/96), Lebanon’s Minister of Labor Mustafa Bayram stressed that he is working to “maintain Lebanon’s image abroad and improve its human rights ranking”. He said that in light of information provided by the International Labour Organization (ILO) about grave practices in Lebanon that may constitute human trafficking, he had decided not to license any new agencies for recruiting foreign domestic workers. Consequently, he was working to effectuate the standard employment contract, which “will govern the licensing of any new agency and the operation of existing agencies, along with domestic work in its entirety, to protect foreign workers from exploitation and abuse and Lebanon’s reputation, dignity, and ranking”.

Given Bayram’s commitment, it is important that we analyze the draft contract as amended by his team and the extent to which the amendments accord with his promises and Lebanon’s commitments to international agreements on human rights in general and migrant workers’ rights in particular. The Legal Agenda obtained a copy of the new version.

The new amendments were made to the standard employment contract adopted by the previous minister of labor, Lamia Yammine, on 8 September 2020 and challenged by the Syndicate of Owners of Recruitment Agencies Lebanon (SORAL) before the State Council. On 14 November 2020, the State Council issued a preliminary decision suspending the Yammine-issued contract as “it was evident from the casefile that implementation could cause the plaintiff [SORAL] serious damage and the petition is based on significantly serious grounds”. One of the State Council’s main criticisms appeared to be that it was not consulted in advance about the contract’s content, contrary to the principle that this institution be consulted about all regulatory decisions before they are issued.

The State Council: The Minister of Labor May Not Enact a Standard Contract

To avoid similar criticism, Bayram endeavored to consult the State Council regarding the contract he is proposing. However, this time the State Council’s answer was categorical. It held that issuing a standard contract “requires a law rather than a ministerial decision” and “domestic work falls outside the Labor Code”, as Essam Ismail – legal advisor to the minister of labor – told the Legal Agenda. After stressing that the amendments to the contract are not final, Ismail said that the minister is investigating how it can be put into effect following the State Council decision. One means is to make it optional, “but Minister Bayram has not yet made a decision on this matter”. The Legal Agenda was unable to view the State Council’s opinion, which is one of the documents that the Right to Access to Information Law does not encompass.

Commenting on this opinion, lawyer and executive director of the Legal Agenda Nizar Saghieh said that, given the complexities of governmental and legislative work on socially sensitive issues, a standard employment contract adopted by the minister of labor is the only avenue for reform:

“It has been the only gateway for reform available for approximately 20 years, i.e. the gateway through which it is possible to adopt amendments, even limited ones, as occurred recently with the standard contract that Minister Yammine announced. Hence, if the State Council really deemed the minister of labor not competent to adopt such a contract, it has closed the one viable means of reform.”

Saghieh described how legislation on this issue stalled under previous governments. All bills to amend the Labor Code or enact a law specific to domestic work presented under labor ministers Boutros Harb, Charbel Nahas, and Salim Jreissati were aborted. While supporting a minister-issued contract in principle, Saghieh has many reservations to the one proposed by Bayram. He also warned against making the contract optional:

“If the contract is optional, that simply means nobody will use it. Given the enormous imbalance between the worker and employer, it is hard to imagine that the former will require the latter to sign this contract when he isn’t compelled to do so”.

Who Did Bayram Consult?

Besides the State Council, who did the Ministry of Labor consult? This question arises because Zeina Mezher from the ILO told us,

“We were not consulted regarding the new amendments. We think it’s best to launch a social dialogue stemming from a rights-based approach to the issue of migrant labor as a whole. That includes the standard employment contract, which is one part of an integrated plan, not something that is seperate”.

Mezher added that “the spirit of the standard contract adopted in the days of Minister Lamia Yammine centered on protecting domestic workers from forced labor” and “the spirit of any approach to migrant labor and domestic work must emanate from here, i.e. from protection from forced labor”.

When we asked Ismail about the consultations, he explained that, “Minister Yammine previously coordinated with the ILO, which was aware and approved of the version’s content, and with rights organizations. Hence, we wanted to save time and not wait long to finish the amendments”.

On that basis, he said that the ministry limited its consultations to the National Commission for Lebanese Women (NCLW) and SORAL.

Unfulfilled Promises to Reform Domestic Workers’ Conditions

Saghieh described the proposed amendments as a “retreat from many of the steps to reform the conditions of domestic workers in Lebanon that the Ministry of Labor previously promised in the days of Lamia Yammine, even though the contract she proposed was not ideal”.

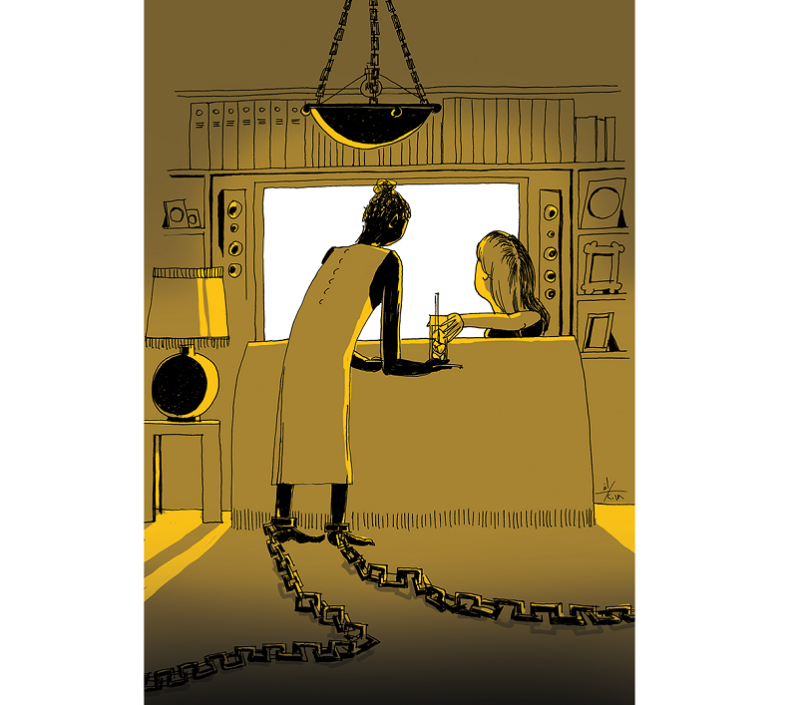

He sees the removal of the article guaranteeing the worker’s right to keep her identification papers (such as her passport and residency permit) as “the ministry rethinking another self-evident right” and says that it “limits the worker’s freedom of movement and to leave and enter”.

Saghieh said that the new contract “also circumvents the worker’s right to leave the job at one month’s notice by requiring that she compensate the employer for the recruitment expenses, either from her own pocket or from the pocket of the new employer to whom she may wish to transfer”. He pointed out two issues:

“Firstly, contrary to Yammine’s contract, the worker has been forced to pay this compensation out of her own pocket if she wishes to return to her country before the contract ends or the new employer does not want to pay. In practice, this could prevent her from exercising this right because she cannot afford to pay. Secondly, the equation for calculating the employer’s losses based on the remaining contract period, whereby the total recruitment cost is divided by the number of months in the contract and the new employer bears the cost of the unused months, was deleted.”

This change opens the door for abuse and extortion, and the emergence of forms of slave trade. Saghieh added, “This circumvention renders the recognition of her right to unilaterally terminate the contract a fantasy, bringing us back to square one, where ‘flight’ is the only means of ending an unhealthy relationship. This issue is exacerbated by the extension of the contract period from two years to three, which increases the employer’s demands”.

Saghieh noted that Yammine’s contract “placed the burden of compensation on the new employer [if the worker wishes to transfer] or the recruitment agency [if she wishes to return to her country]”. The current contract “totally frees the recruitment agency from any burden and allows the compensation to be collected from the worker herself”. He also criticized the choice to allow the contract – and by extension the worker – to be bequeathed irrespective of her view on the matter: “What if the employer’s heir is bad or violates workers’ rights and she doesn’t wish to work for him?”

Saghieh also mentioned that the contract undermines the worker’s job stability by allowing the employer to terminate it unilaterally or on flimsy grounds (e.g. two verbal warnings) without paying any compensation. Regrettably, the ministry justifies this choice on the basis that it affords equal rights to the worker and employer. In reality, the right granted to the worker is a mere fantasy as it is contingent on paying compensation that she may be unable to afford. The right granted to the employer, on the other hand, is a new privilege that can be brandished to compel the worker to accept the most heinous forms of exploitation.

While the previous contract guaranteed the worker her “own separate, well-ventilated, well-lit room that meets sanitary requirements, that is equipped with a lock for which only the worker has a key, and where her privacy is respected”, the new contract “allows” her to share the bedroom of a female member of the employing family. Saghieh said that this amendment circumvents the worker’s right to privacy. It also undermines “her right to nighttime rest as she will perform housework during the day and take care of the elderly at night, thus working long hours without rest”. He added that “both contracts remain silent about the worker’s right to choose between residing in her workplace and choosing separate accommodation”.

Saghieh also addressed the deletion of “another self-evident right, namely the prohibition on confining the worker [Article 9], which includes practices like locking the door on her and preventing her from going out during time off and holidays”. Not only does the new proposal omit this article, “it also sanctions confinement during the three-month probation period on the pretext of protecting her from any external exploitation by making her right to go out contingent on the employers’ accompanying her”. The contract thereby legitimizes employers’ perpetration of the felony of deprivation of liberty, all to protect the interests of the agencies, which could incur losses if the worker abandons the home during this period.

Finally, Saghieh mentioned the danger of including in the contract an arbitration clause under which the minister of labor appoints a ministry employee to make a final, unappealable decision on the dispute. In practice, this clause strips the worker of the right to litigate before an independent and impartial judicial authority. This is very concerning, especially given the suspicious connections between many Ministry of Labor employees and recruitment agencies.

The Ministry of Labor: We Are Open to Feedback

Responding to Saghieh’s comments, Ismail said that the amendments to the standard contract “have not yet come out in their final form, and we’re open to any serious feedback”. But he stressed that laws “must be realistic because the law is a mirror of reality. We want to be mindful of all sides – the employers, the workers, and the recruitment agencies. We’re not in Plato’s Kallipolis, and we want a text that can be applied. We can’t enact an ideal text in a state in disarray”.

While the new contract omits the clause linking the worker’s wage to the minimum wage, Ismail promised to amend these points. He said that the clause prohibiting the worker from leaving the house without the employers’ company during the first three months “came in response to a demand by SORAL, which has experience with some workers coming to Lebanon and then leaving the employers’ homes as soon as they arrive after connecting with any [third] party or people”. The removal of the worker’s right to keep her papers was also requested by SORAL, according to Ismail. He said that the ministry “left this matter up to an agreement between her and the employer”, but he promised to consult the minister on this point: “It needs the minister’s decision. I can’t decide on it”.

Regarding the choice to make the worker’s right to leave the job at one month’s notice contingent on compensating the employer for recruitment costs, Ismail said that some workers “are coming for a week or month and deciding to leave for no reason, and employers can no longer afford to tolerate temperamental decisions”. He added that the amendment nevertheless “places controls on the use of this right rather than abolishing it”.

Responding to all the feedback on the amendments, Ismail says, “Research hasn’t finished, and we will announce a final version as soon as the finishing touches are added”. Yet the ministry already lodged the amended contract with the State Council so that it could provide its opinion.

Claudine Aoun: We Have Not Seen the Final Version

When we contacted NCLW President Claudine Aoun, she said, “We have not received the final version yet, and as far as I know, it doesn’t violate the workers’ rights but improves them based on the consultation process in which we participated”. She added, based on what she called “the experience on the ground with the workers”, that “there are transgressions from both sides – the employers and the workers”. She said that workers “are sometimes lured into conduct, behavior, or actions that are illegal and unsafe for them”. She mentioned that the NCLW held a meeting with agency owners to coordinate on the amendments to the standard contract: “They have to agree to the amendments as they are the ones who challenged Yammine’s contract”. She added that the NCLW’s legal team deemed that the contract Yammine had adopted “was biased toward the workers and didn’t honor the interest of both sides, i.e. the employers too”.

SORAL President: Pressure Informal Labor

On his part, SORAL President Joseph Saliba confirmed that a virtual meeting was held with the NCLW: “We gave our feedback”. He said that the contract “preserves the rights of all sides and guarantees more freedom for the worker”. He mentioned that SORAL had feedback on phrasing, as well as on linking the worker’s salary to the minimum wage:

“The salary should be defined in the agreements that the ministry makes with the countries from which we recruit workers rather than based on the minimum wage. That’s because the worker today takes five times the minimum wage amid the collapse of the Lebanese lira, while she receives 200 dollars”.

Saliba called the issue of assigning the worker her own room a “small detail” and said that “lodging her with a female in the home accommodates the idea that she may be caring for an elderly woman”. He added, “Not all employers have the ability to devote a room to the worker, too”. He said that SORAL’s demand concerning withholding identification papers was limited to the residency permit: “We’re not against giving her her passport. But we asked that she be given a photocopy of the residency permit, lest she leave the country without the employer knowing or being able to prosecute her if she committed a crime against him or a family member”. He denied that this clause is intended to accommodate the interests of agency owners. He also denied that SORAL is responsible for the clause prohibiting the worker from going out unaccompanied during the first three months: “It was there, and we weren’t the ones to place this condition”.

In closing, Saliba said that he hopes that the employment contract will be accompanied by “police attention to the out-of-control situation in some areas and neighborhoods that have become places for workers to escape legal controls and papers”. He said that there should be “a campaign on these areas” where “humans are trafficked and young working women are exploited and lured into illegal acts”.

Mapped through:

Access to Information, Administrative Authorities, Domestic Work, Inequalities, Discrimination and Marginalisation, Law Proposal, Lebanon, Marginalized groups, Right to Life, Unions and Syndicates

Related Articles