Irregular Migration in Kais Saied’s Discourse

On 25 July 2021, Tunisia’s President Kais Saied announced that he was suspending Parliament and taking over most major authorities and powers. Days later, Ennahda leader and speaker of the since-dissolved Parliament Rached Ghannouchi delivered a statement to major Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera warning Europe that it would see a large wave of irregular immigration from Tunisia if Tunisian democracy were not restored. Ghannouchi did not choose an Italian newspaper at random, nor did he dramatize the figures (half a million migrants by his estimate) for no reason. Italy is the gateway to Europe, which has for many years been witnessing an obsession with closing borders and rising xenophobia. With his statement, Ghannouchi sought to “scare” Europe and incite it against Saied using the migrants issue – a card previously played by late Libyan President Muammar Gaddafi and current Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan when their relations with the European Union grew complicated.

Saied responded quickly. In a meeting with the Italian ambassador on 1 August 2021 to receive a shipment of COVID-19 vaccines, Saied said that certain parties are trying to increase the number of irregular migrants and cause chaos by recreating the February 2011 scenario (when over 20,000 Tunisian migrants arrived on Italian shores within days). He warned of “attempts to exploit this issue politically at this delicate period in the country’s history”. The president also spoke about political exploitation a year earlier while visiting two of the main “platforms” for haraga [a Tunisian term for irregular migration derived from the act of burning identity documents], namely Sfax and Mahdia governorates, to check police and military readiness to tackle the boats:

“Irregular or illicit immigration is today being organized for political reasons… I was with a number of people whose migration had been thwarted. There are people encouraging [irregular migration] in order to say or suggest that the electoral process, particularly the presidential electoral process, has not achieved the Tunisian people’s goals”.

These were not the only occasions on which the president addressed the irregular migration issue. It is a recurring subject in many of his speeches, interviews, and discussions with Tunisian and foreign officials. To understand his perspective and stance on the phenomenon and the solutions he proposes, I reviewed many of his statements from June 2020 to today. Four themes appeared in most of these statements.

Mixed Terminology

When speaking about irregular migration, Saied uses several different terms and phrases from one speech to another and occasionally within the same speech. Sometimes he uses the “neutral” descriptor, namely “irregular”. Sometimes he describes it as “illegal”, “illicit”, or “illegitimate”. Sometimes he labels it “secret” or “clandestine sailing”. While all these terms refer to the same phenomenon, they have different tones. Most have negative connotations of crime, wrongdoing, and stigma, especially when spoken by a state’s president, whose every word bears a certain weight and impact. This terminological mess is unbecoming of a top state official whose team of aides and advisors is supposed to revise his speeches and alert him to flaws and the need to rectify them.

A Legal Misunderstanding

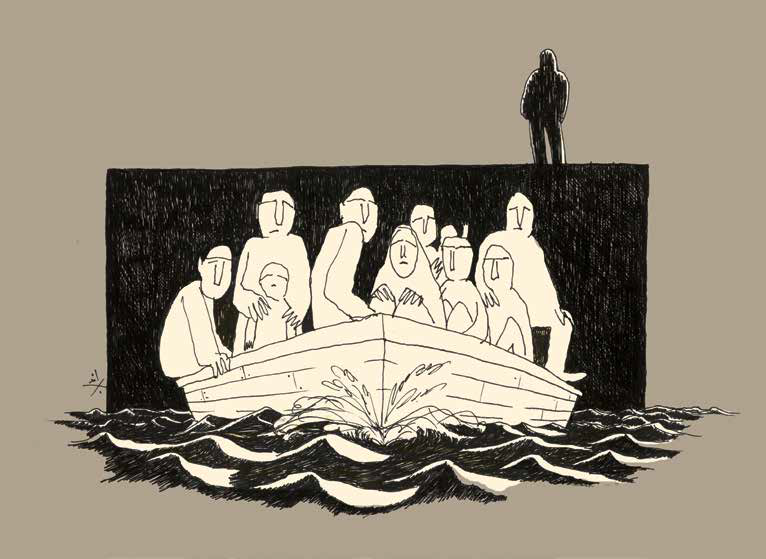

Saied frequently talks about irregular migration as human trafficking, reducing the phenomenon to “misguided” youth seeking to cross the borders and subsequently exploited by organized crime gangs in Tunisia and again upon arrival in the “northern countries”. This legal characterization could apply to some organizers of migration journeys and intermediaries, especially for non-Tunisian migrants. However, boarding the boats is usually a free choice made by the emigration-seekers. Both the emigrant and the person they pay to deliver them to their destination by illegal means know the dangers and obstacles that the agreement entails. Even the definition of human trafficking found in Organic Law no. 61 of 2016 (issued 3 August 2016) on Preventing and Combating Human Trafficking does not encompass irregular migration.[1] In other words, the conflation of irregular migration with human trafficking is an arbitrary interpretation that often stems from a political stance and a desire to crack down on it. Such crackdowns have not proven effective or stopped the “death boats”. They have only made irregular migration more dangerous, more costly in terms of money and lives, and more attractive to human trafficking gangs. Focusing on “human trafficking gangs” also means ignoring the reality that irregular migration and its dangers are the direct product of the European Union’s immigration policies, as well as the southern countries’ submission to the northern countries’ dictates and their willingness to serve as Fortress Europe’s border protection agent. It is also a logical consequence of the division of the world – due to colonial and neo-colonial policies – into fortunate, attractive countries and countries that alienate and drive away their people.

A Blatant Contradiction

Almost every time Saied has spoken about irregular migration in interviews and live speeches in Tunisia or discussions with European officials in Tunisia and abroad, he has mentioned that a security-based and legal approach is insufficient to address the complex phenomenon and its socioeconomic roots. Responsibility for finding solutions, he says, falls not only on the origin countries but also on the northern countries:

“More important than the security approach is providing work that upholds human dignity and establishing development projects. This should involve combined efforts by all the countries, which would help change youth’s perspective on their situation and countries, and give them hope of a better life in their homelands, far removed from throwing themselves toward an unknown future.”[2]

“We must handle this issue from all angles, not just the one angle of poor, miserable migrants without hope in life… The issue cannot be addressed from one side, nor can it be handled via a purely security-based approach.”[3]

“The traditional policies for managing irregular migration have proven limited… An approach that allows encouragement of regular migration in accordance with mechanisms that protect migrants’ rights should be adopted.”[4]

“There will be no security or peace until we eliminate the causes of this migration described as irregular or illicit. People do not migrate because they love migration but because they are compelled by lost hopes and dreams.”[5]

This is the tip of the iceberg of statements by Saied about the need to understand the roots of irregular migration and adopt comprehensive approaches to address it. They contradict the rhetoric about crime, wrongdoing, and legal stringency in his other statements.

However, a more blatant and dangerous contradiction is that between these statements and actions and the policies on the ground. Facts show that Saied is following in the footsteps of his predecessors in handling the irregular migration issue. On 28 September 2021, the French government announced that it was reducing the number of visas granted to Moroccans and Algerians by 50% and to Tunisians by 33% because their countries were not cooperating sufficiently with the deportation of irregular immigrants. Saied called his French counterpart to convey his “regret” about the French government’s decision and his vision for solutions and approaches. He expressed no condemnation, anger, intent to summon the French ambassador, or, God forbid, threat of reciprocity (though such a decision would be virtually impossible given the existing balance of power) – just “regret”. Worse, days later, the Tunisian consulates in France stepped up their cooperation with French authorities and granted hundreds of authorizations to deport Tunisian migrants, according to French government spokesperson Gabriel Attal. From November, these “journeys of shame” enlivened secondary airports such as Enfidha and Tabarka, far away from the public eye. Saied’s “cooperation” also extended to Italy. In 2021, Tunisia topped the list of countries to which Italy deported migrants, with 1,872 Tunisians forced to board planes to Enfidha and Tabaraka. Rather than being circumstantial or limited in scope, this cooperation is codified in semi-secret agreements. In the Saied era, just as in previous eras, Tunisia not only repatriates its “wayward children” but also allocates enormous efforts and financial and human resources to protecting Europe’s borders. In 2021 alone, Tunisian security agencies thwarted 1,748 migration operations and prevented 25,657 Tunisians and foreigners from reaching Italian shores, according to the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights.

A Limited and Unrealistic Vision

Irrespective of the good intentions and the actions contradicting them, there is a clear, multifaceted shortcoming in Saied’s vision and approach to irregular migration. He focuses on Tunisia’s position as an origin country and almost exclusively on Tunisian migrants. He ignores Tunisia’s status as a transit country, which has been constantly confirmed in recent years. More than a quarter of migrants who set out from Tunisian shores toward Italy are foreigners, most from sub-Saharan African countries and, more precisely, West Africa. While waiting to make the crossing, they spend months or sometimes years in Tunisia working in informal economic sectors. They face exploitation by employers and police harassment, as well as racism from some Tunisians. Tunisia today is an origin, transit, and destination country for migrants. This complicated situation poses humanitarian, rights-related, and security problems that the state is still handling in primitive, ineffective ways, namely heavy policing and disregard. The president’s discourse on irregular migration ignores not only the sub-Saharan African countries but also the importance of the regional situation in shaping migration routes. For example, Libya’s complicated political and security situation and Moroccan authorities’ crackdown on irregular migration play a key role in redirecting tens of thousands of people seeking to cross the Mediterranean Sea toward Tunisia. Hence, the issue cannot be addressed through bilateral or trilateral coordination between Tunisia, Italy, and France.

When the president lists “effective” solutions to the phenomenon, such as providing jobs for young people and having the European Union ease regular migration procedures, he ignores the country’s economic situation and its weight in international relations. Unemployment in Tunisia is structural and will not be absorbed within a few years. Strategies for precarious and temporary employment, a murky political situation, and adherence to failed economic and developmental choices will not help Tunisia out of its predicament. Tunisians do not migrate only in search of work. Rather, they also seek quality universal healthcare and education, transport fit for humans, and security and administrative agencies that respect their dignity. The qualities of irregular immigrants are also constantly changing. Today the boats carry not only poor and undereducated young men but also university graduates, girls, women, elderly, minors, and entire families. Meanwhile, Europe certainly does not seem like it will revise its immigration policies or its neocolonial policies in countries south of the Mediterranean. So what means does the president possess to pressure the Europeans to soften their stances? Economic dependence, debt, tourism, olive oil, and royal dates? What tools remain, then, for tackling irregular migration? Realistically, none… except for the police on land, the coastguard at sea, and “journeys of shame” in the air.

Irregular migration is not merely a social phenomenon that can be addressed locally. It transcends Tunisia and the southern countries to raise a question about the existing world order, the distribution of wealth among countries, and north-south relations. It also tests the Tunisian state’s sovereignty, the extent of its subordination to the “European partner’s” dictates, and its respect for human rights. Politicians’ handling of this issue provides a glimpse into their personalities and will or ability to change the situation. In any case, the solution does not lie in conspiratorial discourse or pleasing humanitarian rhetoric contradicted by facts and actions.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] Article 2 reads,

“Human trafficking shall include the luring, recruitment, transportation, transfer, diversion, repatriation, harboring, or reception of persons by use or threats of force or weapons or other forms of compulsion, abduction, fraud, deception, exploitation of vulnerability or influence, or delivery or acceptance of money, benefits, gifts, or promises of gifts to obtain the consent of a person with control over another person for the purpose of any form of exploitation by the perpetrator of these actions or placing the person at the disposal of another for exploitation. Exploitation includes the prostitution or debauchery of others and other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery and practices resembling slavery or servitude, beggary, harvesting organs, tissue, or cells, gametes, embryos, or part thereof, and other forms of exploitation”.

[2] Statement by Saied during a visit to Sfax and Mahdia dedicated to irregular migration and investigating means of addressing it, 3 August 2020.

[3] Interview with Saied by Euronews while in Brussels, 3 June 2021.

[4] Statement by Saied during a meeting with Italian foreign minister Luigi Di Maio in Tunis, 28 December 2021.

[5] Interview with Saied by Euronews while in Brussels, 3 June 2021.

Mapped through:

Articles, Asylum, Migration and Human Trafficking, Libya, Security Agencies, Tunisia, Turkey

Related Articles