Gafsa Phosphate Company: The Manufacture of Impoverishment

“I forgot the state exists. The Gafsa Phosphate Company (GPC) educated me. It paid for our electricity, water, and transportation too. GPC has permeated these towns since 1897. The hospital belongs to the company, and the occupational medicine [department] examines everyone without exception.”

This is how Hussein al-Ruhaili, a researcher in sustainable development from the mining town of Redeyef, describes the historical relationship between Tunisia’s mining towns and phosphate extraction.[1] It is not a normal employment relationship but an entire lifestyle.

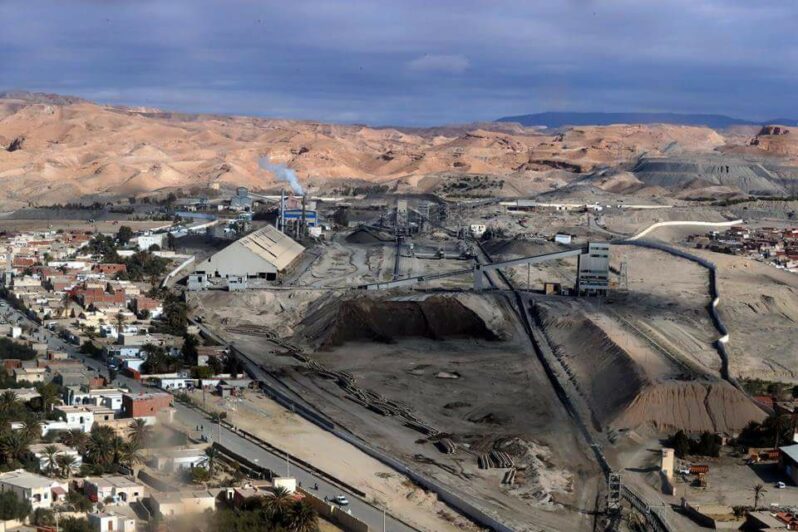

GPC, which has been exploiting the country’s largest phosphate reserve since the beginning of the colonial era, is now heading toward a collapse that threatens to turn the mining towns in the southwest into “ghost towns”. The company has a legacy of contradictions: it grew towns out of nomadism and gave them a new life, yet it neglected to properly integrate and develop them despite its promises. And the residents, whose needs and daily life were tied to GPC, have inherited lung and skin diseases, cancer, yellowing teeth, pollution, water table depletion, and frequent drinking water outages all year round.

Despite the rise in the global price of commercial phosphate from USD88 to USD173 per ton between April 2021 and March 2022, coinciding with the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Tunisian authorities still state that GPC is in financial crisis. In Redeyef, the phosphate washing plant shut down in 2021. Al-Ruhaili tells the Legal Agenda,

“Ceasing production in the Redeyef region means a loss of approximately TND1 billion [USD$330,000] to the economy. For the first time, protests in Redeyef have lasted a year, but there is no official tasked with negotiating with the protesters, who have the facts on their side. Meanwhile, the authorities have resorted to the easy solution, namely importing phosphate from Morocco and Algeria”.

When Phosphate is the Miner’s Sole Identity

Tawfiq Ayn is a retired teacher and an activist from the mining town of Moulares. During his 50 years there, he observed the connection between the discontent in the mining region and the abdication of the state and absence of public services. He tells the Legal Agenda,

“The lack of investment, high unemployment, and low Baccalaureate pass rates are not a new situation but one extending back to the Bourguiba era. There is no political will to develop the mining regions. They remain hotspots of protests. The people feel wronged and disdained. There is nowhere to resort except the cafe. Today, we lack the most basic services, such as hospitals and schools, and private investment won’t come to the land of dust. The state should have driven investment in these regions, but it left us prisoner to GPC. And this giant company, on its part, is heading toward collapse”.

GPC, then called the Sfax-Gafsa Company, was nationalized in 1976. That year, the company’s organic law was issued, and it was separated from the railroad company. Hence, the post-independence state waited 20 years to extend its control over the phosphate sector, which had for decades remained under French control. According to Nada al-Khalifi, a researcher in modern history from the Gafsa region, the discovery of phosphate was a surprise turning point, one accompanied by new ways of life unfamiliar in that unstable trial environment. The newcomers brought with them their customs, ideas, and other things such as newspapers, school, and alcohol. Al-Khalifi tells the Legal Agenda,

“Before 1885, this region was nothing but mountain heights and plateaus inhabited by a few tribes that depended on animal husbandry. This scene would change in 1885, the date of the expedition that included Philippe Thomas, who confirmed the presence of extractable phosphate layers extending for 80 kilometers. The company found itself facing the problem of being a capitalist enterprise operating in a rural environment in a colonial situation, in addition to the region’s geographical isolation and insufficient population. Hence, it dispatched representatives to recruit foreign labor (Europeans and Maghrebis). Consequently, a mosaic of workers quickly formed, and the cores of towns of varying degrees of urbanization were constructed in the mining basin”.

The native inhabitants were uprooted from their desert, and their survival in this semi-arid climate became fundamentally tied to the mine even though they preserved many of their old symbols. From the beginning, the disparity in the mining sphere was pronounced: European neighborhoods consisting of villas with red-tile roofs and containing all utilities form the hearts of the mining towns, while on their periphery lie the neighborhoods of the natives and migrant workers living in tents, huts, and tin homes. Professor of modern history Hafiz Tababi describes this division by saying,

“But recreating an image of the ‘motherland’ was not enough to put these Europeans at ease in this ‘hostile’ natural and human environment. Hence, there is a space between the European neighborhood and the local neighborhoods, one demarcated by industrial equipment, the railroad, the valleys, and the mountain slopes”.[2]

This disparity inherited from the colonial era still frames the relationship of the mining basin’s inhabitants with the state, whose presence is limited to GPC. Phosphate exploitation did not bring deep socioeconomic changes to the mining sphere. In Gafsa Governorate, poverty stands at 22% and unemployment at 28%. From the 1970s, this exclusive dependence on extractive activity would become more of a problem “because of the fierce global competition, decline in export, and the closure and exhaustion of some deep mines”.[3]

Shell Employment Companies to Buy Social Silence

In 1985, GPC was the first public company encompassed by the structural reform program that the state implemented under the auspices of the International Monetary Fund. Thereafter, the company witnessed the most extensive layoffs in its history. Within five years, 5,000 workers were dismissed, and recruitment was frozen. The desiccation of the only source of employment in the region led to protests culminating in the 2008 Mining Basing Uprising, which the Ben Ali regime quelled using security force repression and by trying its leaders. After 2011, GPC witnessed a large disruption in the form of a decline in production and rise in the cost of wages. Al-Ruhaili mentions,

“In 2010, the company employed 4,890 workers and produced 8.5 million tons of phosphate. Today in 2022, the company produces approximately 3 million tons but employs 21,000 workers. There are many executive personnel, whose number multiplied from 300 to 3,700 between 2010 and 2013. In other words, many of them receive wages without working. This has affected the cost of production and the company’s ability to compete. In 2020, the wage bill reached approximately TND600 million [USD196 million]”.

He adds, “GPC is incapacitated not because it is a public enterprise but because of the absence of the government and laws regulating it. Ironically, the company borrows liquidity from banks to pay its workers’ wages while owning a neglected reservoir of approximately 1.5 million tons of commercial phosphate. An intentional and unintentional policy to sabotage this enterprise was adopted. The state is responsible for the underdevelopment because it is absent. It makes no sense for a company operating in a competitive sector like phosphate to be providing garbage bins and means of transport. This company has become a state within a state”.

As GPC is the largest and virtually the only employer in the region given the decline of the other economic sectors, it became linked to the employment issue. Amid the trend toward downsizing labor and relying more on mechanization from the mid-1980s onward, social discontent developed from the company’s declining role in employment. One of the authorities’ solutions to quell the 2008 uprising was to begin establishing subsidiary companies financed by GPC via the Mining Basis Development Fund. The companies were named “Environment, Arboriculture, and Horticulture Companies” in reference to environmental and anti-pollution activities. However, they were a government tool to maintain social stability by creating new jobs without helping to improve the mining towns’ environmental situation or create new productive sectors parallel to phosphate production. Sociologist Khalid Tababi notes,

“Since the post-independence state, GPC has paid a state tax called the ‘environmental pollution tax’. Under the pressure of protests and union activism in 2008, the company – along with some intermediates – circumvented the social demands and the demands of the unemployed such that the region’s anti-pollution entitlements transformed into an employment institution (environmental companies were established but we do not know where the environmental pollution tax was spent). In the absence of developmental and political choices and will, the authority turned to a policy of legal trickery such that the region’s entitlements for combating and mitigating the risks of pollution became a shell institution for employment”.[4]

Post-Phosphate: The Unspoken Future

For many decades, the question of what comes after phosphate has been taboo. What does the exhaustion of this black soil, on which entire towns depend, mean? What is the fate of the residents after GPC’s demise? Most indicators suggest that the coming decades will expose the true extent of the human, environmental, and social devastation. Phosphate is not an everlasting resource. Given the lack of thought about managing its risks and offsetting it with parallel activities, the mining towns will be left to their tragic fate.

Thirst, pollution, and the lack of public services are among the main problems in the mining basin. The establishment of phosphate washing plants in the region beginning in the 1970s has contributed to the exhaustion of water resources and environmental pollution: “Each year, GPC exploits approximately 72% of the mining basin region’s deep groundwater resources, estimated to be 25.1 million cubic meters per year, and approximately 48% of the total water resources in the Gafsa region”.[5] The company also pollutes the ocean and surface water tables via the soiled water it drains after washing the phosphate. Al-Ruhaili also mentions,

“The mining basin towns are still threatened by diseases we thought were a thing of the past, such as jaundice, and diseases that cause teeth to yellow and fall out. This is because of the drinking water distributed in the region and the low rates of connection to the treatment network as the entire governorate has just two treatment plants”.[6]

Agriculture, one of the sectors parallel to phosphate, witnessed little development despite the region’s abundant natural resources. Some agricultural projects still suffer from limited capacities, haphazard exploitation of water resources, and the absence of stimulating public agricultural policies. Moreover, the idea of engaging in this activity as a strategic alternative to phosphate clashes with the mining mentality, which remains attached to GPC, whose influence extends into the fabric of social and cultural relations. GPC also lies at the center of tribal, political, and unionist conflicts because of the prominence of its offices, machinery, operations, and daily dynamics in the inhabitants’ lives. Hence, the company has come to “encapsulate and testify to the region’s history”.[7]

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] The mining towns are Redeyef, Metlaoui, Moulares, and Mdhila. They are located in the southwestern governorate of Gafsa and constitute 60% of its area. According to the latest statistics (2014), the population of the mining basis is approximately 107,000.

[2] Hafiz Tababi, Min al-Badawa ila al-Manjam, 1st ed., La Maison Tunisienne du Livre, Tunisia, 2012, p. 202.

[3] Aisha al-Tayib, “al-Tahawwulat al-Hadariyya bi-Manatiq al-Istighlal al-Manjamiyy bi-l-Maghrib al-‘Arabiyy: al-Manatiq al-Manjamiyya bi-l-Janub al-Tunisiyy Mithalan”, Insaniyat, is. 42, October-December 2008, p. 47.

[4] Khalid Tababi, “al-Rihanat al-Ijtima’iyya wa-l-Iqtisadiyya li-l-Tashghil al-Hashsh: Sharikat al-Bi’a wa-l-Ghirasa wa-l-Bastana bi-l-Hawd al-Manjamiyy Namudhajan”, Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights, 2019, p. 27.

[5] Hussein al-Ruhaili, al-Ma’ wa-l-‘Adala al-Ijtima’iyya bi-l-Hawd al-Manjamiyy, Friedrich Ebert Foundation Publications, 2018, p. 91.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Al-Habib al-Mabruki, “Thaqafat al-Mu’assasa wa-l-Tahawwulat al-Ijtima’iyya: Sharika Fusfat Qafsa Mithalan”, doctoral thesis in sociology (supervised by Muhammad Najib Butalib), Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of Tunis, 2005-2006, p. 93.