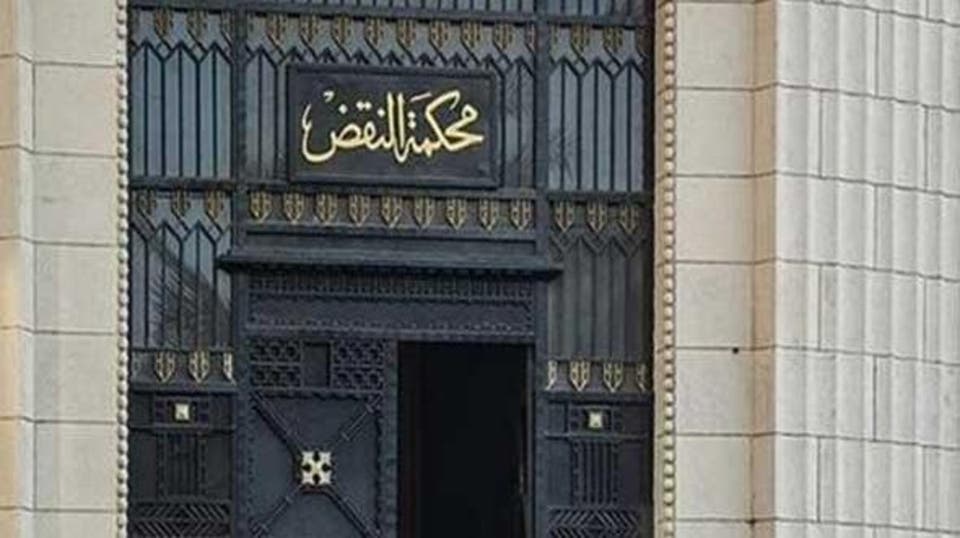

Egyptian Court of Cassation Deems Assembly a “Crime That Violates Honor”

In the latest of a series of controversial legal principles recently adopted by the Court of Cassation,[1] the court’s Labor Circuit deemed assembly to be one of the “crimes that violate honor”[2] in an appeal concerning compensation for a worker’s dismissal from the Alexandria Petroleum Company.[3] According to the facts in the appeal, which was examined in 2019, the company terminated the employee after he was convicted of the crimes of assembly and displaying force in 2014. This it did on the basis that these crimes constitute treason and a deviation from conduct appropriate for maintaining the dignity of employment and therefore fall among the “crimes that violate honor”, which allow the company to terminate a convicted worker.[4] Consequently, after the employee was later acquitted of all charges on appeal, he filed a labor claim demanding compensation for his dismissal. Despite the acquittal, the Labor Court dismissed the compensation claim, arguing that the dismissal decision’s validity must be determined in relation to the time of its issuance. However, the Court of Appeal saw differently: it compelled the company to compensate the employee for what it deemed an arbitrary dismissal. The company appealed this ruling in the Court of Cassation, which supported the company’s view that assembly is among the honor-violating crimes that allow it to dismiss a convicted employee without any compensation.

In fact, the Court of Cassation ruling raises many legal points and issues. However, this article will focus on what a crime that violates honor is and the inappropriateness of applying this label to the crime of assembly. It will also shed light on the issue of conflicting judicial principles issued by the various circuits of the Court of Cassation. This conflict appeared clearly when this ruling was issued and the court’s conclusion that assembly is a crime that violates honor was adopted as a judicial principle even though it totally contradicts another Court of Cassation ruling issued in 2017.

Why Is Assembly Not a Crime That Violates Honor?

The company’s termination decision cited its internal statute, which governs workers’ affairs and the means of disciplining them and allows the termination of workers who receive custodial sentences for crimes that violate honor and integrity.[5] Consequently, deciding whether assembly is one such crime is the main question that the court faced in order to determine the legitimacy of the termination, at least from a procedural perspective. Hence, we must address the nature of a crime that violates honor and the definition of misdemeanor assembly to show how the court went astray in its aforementioned stance.[6]

While there is no definition of crimes violating honor in any Egyptian law, some of their features have taken shape via an enormous number of Court of Cassation and Supreme Administrative Court rulings issued over several decades.[7] For example, frequent criminal and administrative rulings have held that a specific crime or act cannot be named and deemed to violate honor; rather, the type of act and the circumstances of its perpetration are the decisive factors. The Court of Cassation supported this stance in one ruling that held that “characterizing the crime and labeling or not labeling it a violation of honor is a power exercised by the administrative judge alone in accordance with the type of act being punished and the circumstances of its perpetration”.[8] Moreover, the Supreme Administrative Court has concluded that “these crimes can be defined as those stemming from a weakness in character or deviance in nature, taking into account the type of crime, the circumstances of its perpetration, the actions that constitute it, and the extent to which it shows influence by lusts and caprices and misbehavior”.[9] The Court of Cassation repeated this notion in the ruling in question when it stated that such crimes are those that “stem from a weakness in character and deviance in nature”.[10] In ourmy view, given the aforementioned judicial precedents, assembly cannot under any circumstance be considered a crime that violates honor because it is unrelated to weak morals or integrity or poor character, which is absolutely apparent in other crimes like fraud and theft.[11]

In fact, assembly was not the only crime that the ruling labeled a violation of honor. Rather, it included several other crimes without mentioning the reasons that each should be branded with this descriptor. In an unjustified conflation, the ruling decided that assembly, displaying force, blocking roads, shooting, and bloodshed are all crimes that violate honor as they neutralize the provisions of the laws and Constitution, prevent the state institutions and public authorities from performing their work, and impinge citizens’ personal freedoms and other public rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution and law.[12] This troubling perspective warrants further examination below.

How Does the Court See the Crime of Assembly?

That the Court of Cassation sees assembly – with its connection to protesting – the same way that it sees extremely serious, destructive acts such as displaying force, shooting, and shedding blood is a very grave matter that reflects its perspective on people convicted of this crime. Furthermore, this view of assembly as a neutralization of the Constitution’s provisions and impediment to the state institutions’ work assigns the act more gravity than that borne by its potential results, which reveals the court’s political bias regarding the people convicted of it.

People charged with assembly are generally political opponents arrested in a demonstration or gathering,[13] workers demanding their rights and entitlements,[14] football fans,[15] or even outlaw groups in some instances.[16] Contrary to the court’s conclusion, it is difficult or even nonsensical to describe the actions of such people as a weakness or deviation of character. Likewise, they certainly do not arise from lusts or caprices that warrant branding a person with a bad character or reputation. Hence, the court should have paid attention to the political and temporal context in which it was issuing such a ruling. It should have taken into account the large number of people charged with assembly over the past seven years and the repercussions that establishing assembly as a crime that violates honor could have on their lives and careers.[17]

From another angle, the Court of Cassation ignored the ruling that the same circuit issued in April 2017 concluding that assembly is not among the crimes that violate honor.[18] That case closely resembled the 2019 case as it concerned an employee’s termination after he was convicted of assembly. In stark contrast, the court concluded in that ruling that, “The crime of assembly is not among the crimes infringing honor, integrity, or public morals, nor is it a breach by the worker of his contractual obligations. Hence, he may not be terminated on account of his conviction of this crime”.[19] This leads us to discuss another issue, namely the conflict of judicial principles issued by the various Court of Cassation circuits, its effects, and what the court must do to eliminate this phenomenon, which has escalated over the past period.

When the Judicial Principles Issued by the Court of Cassation Conflict: Diminished Authority

By default, the judicial principles issued by the Court of Cassation are constant and stable because of their extreme importance and influence over people’s fates and needs. At the same time, a need to abandon one of these principles and adopt a conflicting or even diametrically opposed principle may occasionally arise because of a legislative amendment or a social development that imposes a new understanding of certain phenomena or actions or because the court discovers that it previously made an error and seeks to correct it.[20] Judicial Authority Law no. 46 of 1976 accounted for this possibility when it regulated the procedures and controls for abandoning a judicial principle issued by either the same circuit or another one: “If one of the court’s circuits sees fit to abandon a legal principle established by previous rulings, it shall refer the case to the competent panel in the court to decide on it, and the panel shall issue its abandonment rulings via at least a seven-member majority. If one of the circuits sees fit to abandon a legal principle established by previous rulings issued by other circuits, it shall refer the case to both panels combined to decide on it, and the rulings in this instance shall be issued by at least a 14-member majority”.[21]

Hence, when the Court of Cassation deemed assembly a crime that violates honor in 2019, it should have referred the case to the court’s Civil Matters Panel for it to decide whether to adopt this new principle or persist with the 2017 principle that assembly is not among such crimes. From another angle, the court’s Technical Bureau published the 2019 principle in its semi-periodical publication al-Mustahdath, which contains the newest principles decided by the various circuits, while the 2017 principle remains published on the court’s website without any indication of the 2019 ruling. Such a conflict poses a grave danger to the authority of the principles that the Court of Cassation issues and opens the door for disputes between the supporters of each opposing perspective, thereby undermining the primary purpose of the court’s adoption of stable legal principles, namely to standardize legal interpretations and their applications.

Conclusion

The key consequences of the Court of Cassation’s April 2019 ruling deeming assembly a crime that violates honor is that people convicted of it may face social stigma, be equated with perpetrators of heinous crimes like shootings and bloodshed, and be considered to have a weak character or deviant nature. This development coincides with legislative steps that discredit such people, such as Parliament’s abolishment of conditional release in assembly crimes along with other crimes like drug dealing and money laundering.[22] At the same time, it has become clear that the Court of Cassation’s circuits must put the Judicial Authority Law’s articles on the procedures for abandoning stable judicial principles into effect. Likewise, it must develop a mechanism that guarantees compliance with those principles without removing the right to abandon them if factors justifying that course of action appear.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Egypt, Court of Cassation, Crime, Assembly, Honor

[1] Ahmad Saleh, “Mahkamat an-Naqd Tafridu Raqabataha fi Taqdir al-‘Uquba: Ijtihad Mabda’iyy li-l-Hadd min ‘Uqubat al-I’dam am Ijtihad Mun’azil?”, The Legal Agenda, 2 April 2020.

[2] Mohamed Farag, “al-Naqd: Jara’im al-Tajamhur Mukhilla bi-l-Sharaf.. Fasl al-Muwazzaf al-Mudan bi-Irtikabiha Qanuniyyan”, Al Shorouk, 2 June 2020.

[3] Appeal no. 2527 of judicial year 88, Court of Cassation, Labor Circuit, 16 April 2020 session.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] According to Article 1 of Assembly Law no. 10 of 2014, the crime of assembly requires at least 5 people and a breach of public peace.

[7] Ahmad Saleh, “Mahkamat an-Naqd”, op. cit.

[8] Appeal no. 1413 of year 07, Technical Bureau 10 p. 1113, Court of Cassation, 24 April 1965.

[9] Supreme Administrative Court ruling no. 5086 of judicial year 24, 22 September 1996.

[10] Appeal no. 2527, op. cit.

[11] Ahmad Saleh, “Mahkamat an-Naqd”, op. cit.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “9 Munazzamat Huquqiyya Tujaddidu Matlabaha Waqf al-‘Amal bi-Qanun al-Tajamhur bi-Misr”, Arabi21, 31 January 2018.

[14] Ahmed Ismail, “Difa’ ‘Ummal Asmant Tourah Yadfa’u bi-Intifa’ Arkan Jarimat al-Tajamhur wa-Muqawamat al-Sultat”, Youm7, 18 June 2017.

[15] Ahmed Ismail, “Bad’ Nazar Isti’naf al-Niyaba ‘ala Bara’at 4 A’da’ bi-‘Ultras Ahlawy’ min Tuhmat al-Tajamhur”, Youm7, 17 June 2017.

[16] Karim Osman, “3 Ittihamat fi Intizarihim.. al-‘Uquba al-Qanuniyya li-Mu’taridi Dafn Tabibat al-Daqahliyya”, ElWatan News, 12 April 2020.

[17] For more details, see Ahmad Saleh, “Mahkamat an-Naqd”, op. cit.

[18] Appeal no. 14770 of judicial year 85, Court of Cassation, Labor Circuit, 12 April 2017 session.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Dr. Awad Muhammad, “Ta’liqat ‘ala Ahkam al-Qada’: Dirasa Naqdiyya li-Ba’d Ahkam Mahkamat al-Naqd”, Dar El Shorouk, 2017, p. 11-12.

[21] Article 4 of Judicial Authority Law no. 46 of 1972 and its amendments.

[22] “Mashru’ Ilgha’ al-Ifraj al-Shartiyy fi Jara’im al-Tajamhur fi Misr: Khutwa Jadida fi Ittijah Ta’mim al-Haya al-Siyasiyya”, The Legal Agenda, 18 February 2020.