Economic and Financial Reconciliation in Tunisia: First Appraisals

On July 14, 2015, the Tunisian Council of Ministers ratified a draft law pertaining to “economic and financial reconciliation procedures”, locally referred to as the “National Reconciliation Law”. The bill consists of 12 chapters, all devoted to reconciliation towards ending the legacy of the dictatorship era in Tunisia.

The bill explicitly outlines in Chapter 12 that “the abolishment of all provisions relating to financial corruption and embezzlement of public funds set out in the Basic Law No. 53 of 2013, dated December 24, 2013, on establishing and regulating transitional justice”. Accordingly, the proposed draft law presents a new perspective to dealing with economic corruption files of the dictatorial era that preceded the January 14, 2011 revolution. Such perspective would write off the approach set out by the Law of Transitional Justice.

Due to the importance of this bill, The Legal Agenda presents below its observations, starting with the bill’s basic issues, and ending with an assessment.

Observations about the Content of the Reconciliation Law

These observations pertain to the general amnesty granted to all state employees, reconciliation with businessmen, and amnesty with regard to money exchange violations.

Amnesty to State Employees and the Likes Who Were Implicated in the Corruption System

Chapter 2 of the draft law revokes accountability with regard to state employees and their clients who were involved in corruption cases by virtue of their work, without having benefited financially from it. The same chapter stipulates a general amnesty where “prosecutions, trials, or penalty implementation against them shall be stopped”.

The draft law also cited the fact that employees and officials did not directly benefit financially from the processes of financial corruption as a justification for amnesty. This criterion overlooks that fact that a large number of officials and state employees were intentionally involved in corruption practices, including political patronage to gain certain privileges, which questions the image of victimhood implicit in the draft law’s language.

Regardless of how appropriate this criterion is to granting a general amnesty, closing the file of state employees accused of corruption without conducting any further investigation hinders the dismantling of such system; and, it prevents the disclosure of the names of those who played a role in corrupting the Tunisian administration, thereby thwarting institutional reform as set out in the Law of Transitional Justice.

Reconciliation with Those Who Benefited from the Corruption System

Under the reconciliation draft law, an administrative committee at the level of the prime minister shall be formed, headed by a representative of the prime minister and includes a representative of the Ministry of Justice, a representative of the Ministry of Finance, two members of the Truth and Dignity Commission, and the public designate of the state’s disputes or his representative. This committee shall decide on the reconciliation requests submitted by those who “benefited from actions related to the financial corruption or embezzlement of public funds”. The bill also stipulates that “members of the committee shall be appointed within 10 days of the date of publication of the law in the official gazette”. The commission can convene as long as four out of the six designated members have been appointed. On the other hand, the bill has set a period of 60 days for the submission of the reconciliation requests, as well as a period of 3 months, renewable once, to decide on those requests. As for the committee’s consideration of the requests, the draft law requires that decisions be taken by consensus, in the absence of which a majority vote is required.

The reconciliation committee’s work shall stop all judicial proceedings and suspend limitation prescription periods. According to the draft law, the reconciliation decision compels the beneficiary to pay the Deposit and Consignment Fund, “a sum of money equivalent to the value of the embezzled public funds or the benefit received, adding 5% for each year of the date the embezzlement had occurred”. The reconciliation revenues shall be used “in infrastructure projects, regional development, the environment and sustainable development, strengthening small and medium-sized enterprises, or any other projects of economic nature in the areas where regional development is encouraged”.

It should be noted that the composition and work procedures of the reconciliation committee do not meet the conditions of an independent body.

The lack of independence regarding its structure can be discerned at the following three basic levels:

First:As mentioned earlier, the appointment of four members, out of a statutory 6, is sufficient for the committee to convene. The fact that the Truth and Dignity Commission appoints two representatives on the reconciliation committee shows that the drafters of the bill anticipated a conflict between the reconciliation committee and the Truth and Dignity Commission. Their response, namely doing away with the need to have 6 rather than 4 members appointed, undermines the respect for institutions.

Second:The appointment process does not provide sufficient safeguards to protect the members of interference. The draft law does not address immunities or safeguards to prevent the appointing body from changing its representative in the committee. In addition, it does not address how to replace members. It seems the bill gives authorization to the appointing body to replace its representative in the committee, which violates all conditions of independence in terms of the rights of the reconciliation committee members regarding their appointment, or the stability of their membership in the committee.

Third:The committee’s decisions are taken first by consensus, and in its absence by a majority vote. Adopting the rule of consensus first may actually result in transforming the decision-making mechanism to an opportunity for the appointing bodies to pressure members of the committee to get their approval by consensus.

As they appear in the draft law, procedures regarding the committee’s handling of corruption files lack guarantees of independence. The bill is designed to speed up the closure of financial corruption files. To achieve this, it sets a maximum period of 6 months to tackle cases of corruption. Setting a time limit on investigating short corruption files hinders inductive research.

Accordingly, it is very difficult for the committee to estimate the amount of money embezzled. or the benefit obtained outside the framework of the data provided by the submitter of the reconciliation request. From this angle, setting tight timelines to look into complex corruption files may strengthen the idea of no accountability, and obscure the conditions of independence and professionalism that the reconciliation committee should abide by; being one that is supposed to investigate corruption files before deciding on them. The same lack of accountability goes for the way the issue of smuggled money is dealt with.

Reconciliation with Money Exchange Crimes: Money Laundering

The bill does not tackle investigating the source of smuggled funds or illegal foreign currency trading; but only proposes reconciliation with those who hold these funds. The bill drafters are apparently trying to ensure that these funds keep circulating in the Tunisian economy in exchange for a financial penalty.

It is clear that the bill is mainly focused on what is considered a current economic interest. The bill encourages those who smuggled money abroad or hid it in Tunisia to pump it into the economy. This approach leads to accepting the introduction of corrupt money, and of anonymous origins, into the economy. This choice also results in giving those who possess smuggled funds opportunities to invest their money in Tunisia, boosting their economic and political influence.

In conclusion, the economic approach under which the bill was drafted has focused on quick positive aspects with no regard to the negative impact that may result therefrom. In this context, the negative roles played by corrupt political money in Tunisia’s political life should be studied. A comparison between the approach adopted by the draft law and other approaches would serve the national interest. The draft law should be subject to the various approaches, especially in the context of its relation to the course of transitional justice.

A Draft Law in a Tense Relationship with the Legislative System

The reconciliation draft law aims to [create accountability] in the financial and economic sectors. It explicitly calls for “the abolishment of all provisions relating to financial corruption and embezzlement of public funds as set out in the Basic Law No. 53 of 2013, dated December 24, 2013, on establishing and regulating transitional justice”. The bill’s intervention regarding transitional justice poses a question about the law’s constitutionality. Under Chapter 148 of the Tunisian Constitution, the state “bears the duty to implement all areas of the transitional justice system and the period of time set by its legislation “.[1]

The Tunisian Constitution defines the area of protection for transitional justice to include all fields of the transitional justice system. It is likely that the proposed bill will be considered inconsistent with the fundamental basics of transitional justice; namely, accountability and seeking to dismantle the corruption system. The draft law proposes amnesty to employees who were implicated in corruption, without accountability, and seeks reconciliation with those that have benefited from corruption, without seeking to dismantle the corruption system and uncover the truth. It even permits the laundering of corruption-generated money without questioning its source. As a result, the reconciliation bill limits the competence of the Law of Transitional Justice to human rights violations that do not include those committed by owners of capital funds and high-ranking employees.

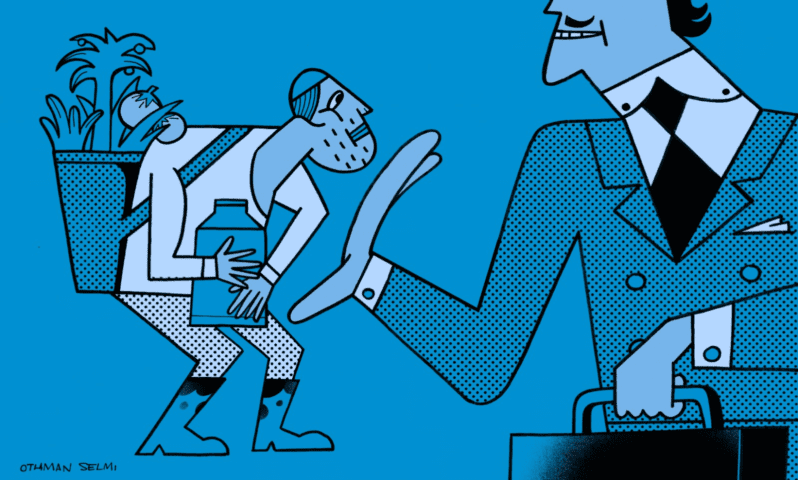

Such an approach results in a faulty justice system: one that stipulates -at the level of the Law of Transitional Justice- punishment against those who committed violations during the dictatorship, and were stripped of their power by the revolution. At the same time, this faulty justice seeks, through the reconciliation law, to rehabilitate those who were involved in financial corruption by granting them amnesty and laundering their money.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] Chapter 148 of the Tunisian Constitution, Article 9.