Aborted Judicial Transfers in Lebanon: When Political Claws Dig Deeper

In late August 2016, “resigned” minister of justice in Lebanon Ashraf Rifi referred a draft decree to the Council of Ministers in order to effectuate judicial personnel transfers. This draft encompassed approximately 190 judges. Although the Supreme Judicial Council was optimistic about passing it, the term of Prime Minister Tammam Salam’s government ended before the ministerial signatures were all obtained. Thus, the Supreme Judicial Council once again failed to pass a judicial transfers decree despite the intense efforts of its president, and some of its members to convince the political actors concerned of the need to do so. One newspaper claimed that the draft’s obstruction probably stemmed from the disagreement between the Future Movement and the resigned minister of justice [one of its estranged members]. Other causes –such as the conviction among some political actors that their negotiating position will improve if they succeed in the presidential election and process of assigning a new prime minister– are conceivable.[1]

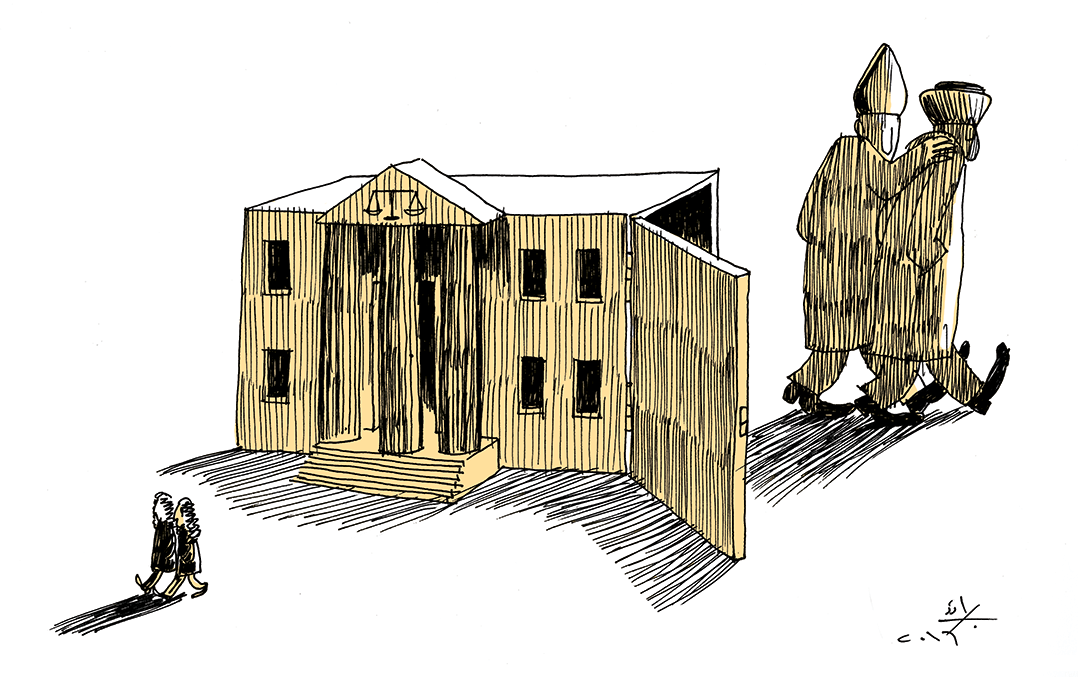

Whatever the true reason, the main issue is the fact that the dominant political forces were able to obstruct judicial transfers drafts, which harms the judiciary’s organization and its independence and effectiveness alike. This transfers draft is not the first to be aborted; rather, it is the latest in a series of drafts aborted for one reason or another, at one stage or another.[2] Despite the gravity of the issue, it is little talked about. There are no judicial protests like those that occur in other countries against the repeated humiliations of the judicial institution. Nor are there even popular protests: the citizens do not seem concerned with the judiciary’s effectiveness or independence.

This judicial and social inaction allows the production of judicial personnel charts to become an effective tool for entrenching extremely dangerous customs in the realm of the judicial institutions’ relationship with the political forces. Worse, it allows for imposing rules of promotion within the Lebanese judiciary and thus establishing the attributes of the “successful” judge and its antithesis, the “failed” judge. The effect is to accustom judges and the judicial institutions (including the Judicial Inspection Committee) to judicial conduct more in keeping with the attributes of the “successful” judge, even if this conduct conflicts with the traditionally recognized conduct of an independent and impartial judge.

The 2001 Reform: Just an Illusion?

The current rules for effectuating judicial transfers trace back to the 2001 amendment to the law regulating the judicial judiciary. This reform constitutes the only publicized attempt at reforming the legislations governing the judicial judiciary since the end of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990). While this law preserved the requirement that the transfers be issued via a decree based on the minister of justice’s recommendation after the approval of the Supreme Judicial Council, it introduced two important changes.

Firstly, the law transferred the task of drafting the judicial transfers decree from the Ministry of Justice to the Supreme Judicial Council. The goal of this amendment was to give the council the first word and thereby enable it to impose its choices at the beginning of its negotiation with the minister of justice. The effect of this transfer of powers is that the minister is obliged to explain their reasons for disagreeing with the council’s draft, which restrains and protects against political discretion. Of course, the more the minister is bound by transparency in this regard, the more important this amendment becomes.

Secondly, the law amended the means for settling a persisting disagreement between the minister of justice and the Supreme Judicial Council. Following much criticism of the previous rules, which gave the Council of Ministers and hence the executive branch the final say, the 2001 law enabled the Supreme Judicial Council to have the final say via a decision for which at least seven of its ten members must vote. However, the lack of effective implementation mechanisms quickly became evident, for on many occasions the minister of justice has acted as though there is no deadline for him to explain his reasons for disagreeing with the council about the transfers draft, or to convene a session with it to overcome the disagreement. He has held onto the draft without any discussion.

Worse, even if the minister does approve the council’s draft, the people whose signatures must be obtained before the decree’s issuance –namely the minister of justice, the president of the republic, the prime minister, the minister of finance, and the minister of national defense– can obstruct it because of the interests of the political forces they cater to. They may even obstruct the decree because of lesser interests, such as favoritism of one judge or another. These authorities have virtually taken turns in blocking these decrees.[3] Making matters worse, any one of them can now act in this manner without being checked by any higher authority because of ministerial and presidential immunities, and because the instruments of political accountability are not functioning. Thus, stripping the Council of Ministers of its power to settle disagreements and transferring it to the Supreme Judicial Council in practice granted the aforementioned figures the right of veto, and thereby made them akin to guardians over the judicial branch. This attempt at reform therefore had the opposite effects to the stated goal, namely, to reinforce judicial independence.

The amendment’s reformist dimensions were also undermined by the fact that it preserved for the government the power to appoint eight of the council’s ten members, restricting the principle that the judges should be elected by their colleagues to only two members. These two members are elected from among the chamber presidents of the Court of Cassation, i.e., from among those who sit atop the judicial hierarchy and who might not have arrived there had the executive branch not approved of them. There is therefore [doubt] that the council can impose a draft judicial personnel chart on the executive branch via a seven-member majority, when eight of its members are appointed by this branch in the first place.

Accustomization out of Fear of Exposure or Accusation of Incapacity

Despite the gravity of the political interference in judicial affairs via the transfers drafts, the Supreme Judicial Council tends toward further accustomization with it. The amount of interference and its recurrence without any real popular resistance seem to have gradually forced the council to treat it as an inevitability. The council sees no way to accomplish any transfers, regardless of how trivial or necessary they may be, without satisfying all the political actors concerned. Oddly, the reform that transferred the power to develop the draft to the council also led to results adverse to at least its stated objectives. The council realized that to produce a viable draft given the rules of power sharing, it could no longer restrict its contact with the ruling authorities to the minister of justice; rather, it is now forced to contact and negotiate directly with all the political forces concerned.

This realization has led to a custom whereby the president of the Supreme Judicial Council, alone or accompanied by other members, visits the officials concerned to listen to their conditions for approving the decree. The council could, of course, cling to a certain puritanism and avoid any negotiation with the political forces to uphold the image of independent and impartial judges, but doing so has a high price: the complete incapacity to make any of the decisions needed to properly administer the judiciary’s affairs. The council’s success therefore depends on its flexibility and its ability to deal with the political actors, and perhaps negotiate with them over their shares in the transfers to obtain their agreement.

Hence, rather than facilitating the production of personnel charts based on objective data or reducing the interference or political discretion, the reform attempt put the council and the transfers draft in the middle of political bargaining and power sharing. Worse, even though the council has respected the rules of the game and dealt positively with them by accepting limited latitude, its attempts and efforts have usually ended in significant failures that on each occasion have forced it to adopt even more flexibility, and reduce its resistance to the names demanded by one person or another.

By contrast, the authorities and political forces have on each occasion discovered an increase in their power to intervene and bargain at no notable cost to their credibility or popularity. Consequently, their appetite and interest in the bargaining has also increased such that some of them now not only nominate judges for sensitive positions (in public prosecution offices and investigation departments) to support their own standing and interests, but also nominate judges close to them out of favoritism and to meet these judges’ demands. Senior judges have confirmed this much in interviews with The Legal Agenda, wherein they stressed that most interventions of politicians in the transfers are requested by judges themselves with a view to achieve their desire to occupy one position or another. In this context, there is much evidence of the large increase of political interventions in the nominations on several levels. Many of those monitoring the latest personnel charts even estimate that the nominations [by politicians] account for 85% or 90% of the positions encompassed by the latest draft (This is based on interviews with a number of judges, some of whom relayed these estimates from several members of the council).

Exacerbating the situation, the Supreme Judicial Council behaves as though it is not –along with the judiciary– subject to a grave violation that compels it to ring the alarm bells and mobilize judges to help it confront and resist. It behaves as though it is sufficiently strong and it is performing its role pursuant to the law’s texts (even if it is hoping and working to amend them).[4] Hence, the council does not warn the public of the gravity of the interventions in the preparation of the transfers draft, or even interact positively with the criticisms directed at the processes involved. Rather, the council takes a defensive stance as any attack on these processes has become synonymous with attacking it –now that it partakes in them– or with contesting its capabilities.

This [defensive stance] manifested clearly in the statement that the council’s media office issued on January 29, 2014. The statement was a response to the criticisms directed at its president, Judge Jean Fahd, for visiting the political authorities with a view to produce the transfers draft in January 2014. In effect, the statement presented a legal-constitutional interpretation that legitimized such practices by accepting the executive branch’s power to intervene in judicial transfers via not only the minister of justice, but also the people whose signatures must be obtained on the transfers decree. This interpretation reflected a retreat by the council from previous interpretations, which had deemed these signatures a mere formality because the legislature had explicitly, and somewhat rejoicingly, granted the Supreme Judicial Council the right to determine the content of transfers drafts via a specific majority, as explained earlier.

The statement went even further and deemed this practice to be founded upon not only the 2001 law, but also constitutional principles, namely “the need for cooperation between the powers and respect for the principle of contact between them for the good of the nation”. On this basis, the statement portrayed the council’s president’s visits to politicians as part of his role as the head of one branch in interacting “with the legislative and executive branches”. Notably, the statement also mentioned the customs that the council’s forerunners had followed in dealing with the political authorities without explaining what these customs were. It thereby left a broad scope for interpretation in this regard and, more importantly, for developing these customs in light of the contact between these unbalanced authorities.

It is no secret that talk of the “principle of the cooperation of powers” as an alternative to the principle of the separation of powers or about “customs” is no more than an acceptance of the encroachment of the political authorities. Such talk legitimizes this encroachment by portraying it as a natural thing that does not call for any discontent or concern. In the same vein, the council has strived to downplay the gravity of this intervention and the politicians’ responsibility for it. Evidence includes Fahd’s statements to The Legal Agenda. Although he acknowledged the interventions stemming from the mechanisms for adopting the transfers decree, he maintained that they are limited and of little significance, and that the council can resist them if they cause any abuse. When asked whether appealing to the public was appropriate in such cases, he responded that the council has never done so and that it relies on the executive branch.[5]

The council has taken one legislative initiative (submitted via MP Robert Ghanem) to amend the law regulating the judicial judiciary, by strengthening its power to decide personnel charts through abolishing the need to obtain a decree. However, this reform remains incapable of accomplishing real reform for two reasons (as The Legal Agenda has explained elsewhere)[6]: it was not coupled with any amendment to the mechanism of appointing the Supreme Judicial Council’s members, and it raised the number of members needed to settle disagreements over the draft personnel charts from seven to eight. In this regard, the question raised earlier is even more pertinent: How can a majority consisting of at least eight of the council’s ten members be obtained in a dispute with the executive branch, when that branch itself appoints eight of them? Hence, the council’s initiative seemed to be aimed more at self-justification and lifting the blame than actual reform.

Wasted Judicial Capacities and Misconduct

The damage that the continuation of this political-judicial bargaining does to the judiciary is widely recognized. It does massive harm, not only to the judiciary’s organization and effectiveness, but also to the conduct and independence of judges.

The preparation of the transfers on the basis of bargaining prevents them from occurring in accordance with objective standards, or even at a specific time (before the judicial year begins) to prevent confusion. Furthermore, if the transfers do not go through (as has occurred many times in the past decade), then several positions are left vacant and, more importantly, many judges who have graduated from the Institute of Judicial Studies are left waiting (perhaps years) to assume their first judicial positions. The result is of course a great waste of judicial capacities at a time where litigants are yearning for these capacities to be put into effect to expedite their cases.[7]

However, the biggest danger lies in the lesson that judges receive with every transfers draft, whether or not it runs its course. The lesson is that promotions are attained via public relations –specifically relations with the political actors or their circles of influence within the judiciary– or, perhaps in certain cases, by ingratiating oneself with and declaring loyalty to these actors. In contrast, a judge’s good performance has less influence over career trajectory, influence perhaps limited to [the acquisition of] positions from which the political forces and judges supported by them abstain. A judge who refuses to resort to the political actors because they adhere to the conduct that an independent judge is supposed to display, and who repeatedly witnesses the results of the transfers will eventually feel vulnerable and will be continually pushed towards more flexible conduct. Such a judge may observe their colleagues end up adopting this flexibility after caving in to this unfair discrimination against them. Additionally, the judicial community around them will act like a large mirror reflecting the concepts of the successful judge (the one who made it) –i.e., the supported judge who succeeds in getting promoted (rises into highest ranks)– and of the failed “puritan” judge that never advances because of their rigidity and mishandling of the situation.

The career as a whole thus becomes akin to a perpetual call for the judge to deepen their bonds with influential political forces, and therefore a tacit amendment of the charter of judges’ ethics, and the independence and impartiality that it prescribes. Neither the judicial institutions nor the judge concerned find fault in being associated with one actor or another as this patronage has become a fundamental and natural part of the promotion game. And there is no harm, when the need for being double-faced presents itself, in dressing up this convergence between judges and politicians by claiming ties of friendship (and why not deep ties?) among them. Consequently, The Legal Agenda’s query about whether any judge has been rebuked or punished on the basis of their closeness with, or flattery of influential persons is an extremely naive one, for the answer is definitely not.[8]

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] See: Radwan Mortada’s, “Khilaf al-Mustaqbal-Rifi Yusqit al-Tashkilat”, Al Akhbar, October 4, 2016.

[2] In May 2015, resigned minister of justice Ashraf Rifi retained a transfers draft. In January 2014, former Prime Minister Najib Mikati rejected the draft. In May 2013, minister of justice Shakib Qortbawi retained a transfers draft.

[3] Former President Émile Lahoud blocked the transfers decree that Minister of Justice Charles Rizk had proposed, with the approval of the Supreme Judicial Council, which was presided over by Judge Antoine Kheir. Former prime minister Najib Mikati blocked the transfers decree proposed by minister of justice Shakib Qortbawi at the beginning of 2014.

[4] Interview with President of the Supreme Judicial Council Jean Fahd, published as “Muqabala ma’a Ra’is Majlis al-Qada’ al-‘Ala al-Qadi Jan Fahd: Awlawiyyatuna Hiya Tahsin Intajiyyat al-Qada’, wa Nuqatil Hin Naksib Thiqat al-Ra’i al-‘Amm”, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 37, February 2016; “There are judges with long-term friendships with politicians, friendships not always stemming from their judicial position.”

[5] Ibid.

[6] See: Civil Observatory for the Independence of the Judiciary, “Naql al-Qudat Wifqa Ma’ayir Mawdu’iyya?”, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 33, December 2015.

[7] See: “2730 Shahr Batala wa Hadr fi al-Qada’ al-Lubnaniy”, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 30, July 2016.

[8] Interview with Jean Fahd, op. cit. “There are judges with long-term friendships with politicians, friendships not always stemming from their judicial position.”