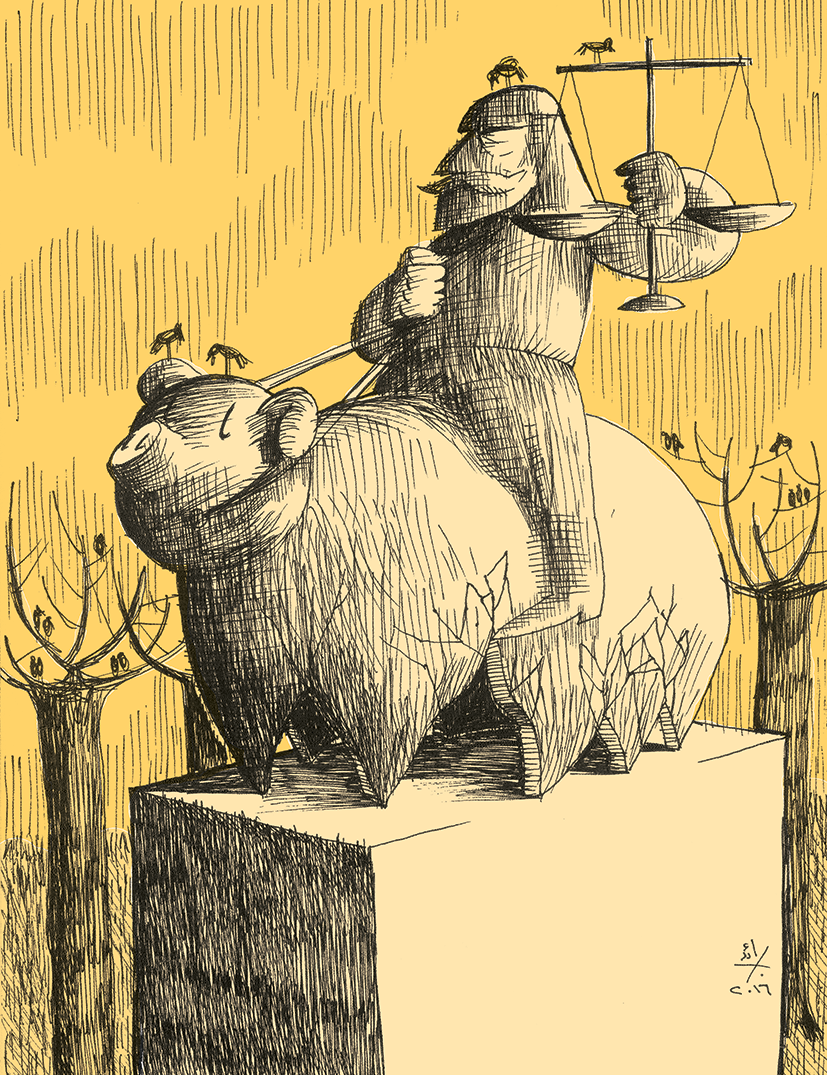

Suing the Superman of Lebanon’s Justice System

On April 27, Public Prosecutor in Mount Lebanon Judge Ghada Aoun filed a suit in the State Council against the decision to bar her from investigating the most important cases pending in her prosecution office, including the case of smuggling money abroad. Ghassan Oueidat had issued the contested decision on April 16, deeming that his authority as cassation public prosecutor (head of the Public Prosecution offices per the Code of Criminal Procedure) allows him to amend the work-distribution decisions issued by a governorate-level public prosecutor. This decision accorded with several of his previous circulars aimed at expanding his powers to control public right cases, particularly those concerning corruption. The Legal Agenda warned of this trend in three articles that it published in 2019 commenting on Oueidat’s circulars: “From the Outset Oueidat Declares ‘I’m in Command’: Two Circulars Threatening the Independence of the Public Prosecution Offices and Anti-Corruption Efforts”, “A New Superman in the Justice System? Part I: Absolute Hierarchy and the Personalization of Public Right”, and “A New Superman in the Justice System? Part II: Hierarchy Facilitates Impunity”.[1] At the time, we wondered whether we were witnessing Oueidat seize superpowers within the justice system in order to control the course of investigation in public right cases, and subsequent events – particularly this contested decision – have confirmed our fears.

While this suit bears much importance in relation to the contention occurring in the money smuggling case, its significance extends further. The State Council’s stance in this suit could influence the organization of the Public Prosecution offices and, in particular, the limits of the cassation public prosecutor’s hierarchical authority. As a result of this authority, public right (i.e. society’s rights) often lies exclusively in this figure’s hands, and the ruling regime can subsequently control these rights by ensuring the loyalty of one person. This occurred via Cassation Public Prosecutor Adnan Addoum, who tailored the Code of Criminal Procedure to the powers that he wanted to exercise, as well as his successor Saeed Mirza. Today, we are witnessing the rise of a new superman in Ghassan Oueidat – which we hope will be hampered by this suit.

A Case to Correct the Debate in the Money Smuggling Case

The contested decision clearly played a pivotal role in the money smuggling case, particularly the characterization of the facts and determination of liabilities therein. Without this decision, Aoun’s raid on the offices of money exchange company Mecattaf would presumably have been a routine and confidential investigation procedure that occurred far from any crowds of supporters or opponents and any cameras. Similarly, the event would have been depicted as a raid – an action that falls within public prosecutors’ powers and, when necessary, their responsibilities – rather than an attack. To be certain, we need only consider that the decision was issued not before the raid, as some imagined, but during and in an attempt to stop it, with the company’s attorney conveying the decision to the judge to justify not complying with any of her orders. The decision thereby laid the foundations for narratives depicting Aoun’s insistence on completing her task as a departure from the law and an act of mutiny. The raid itself was depicted as an invasion or even a trespass on private property. The condemnations intensified as the crowds who came to support Aoun increased, as did warnings about the transformation of justice into populist stunts or trials. When the company then went so far as to lock the door on Aoun, citizens and the judge’s bodyguards together removed the door so that the company could be raided, and this spectacle compounded the narratives denouncing Aoun.

While most narratives focused on the aforementioned spectacles and depictions, the issue of the legality of the decision that gave rise to them was ignored or treated as irrelevant to Aoun’s obligation to comply with it and the condemnation of her mutiny against it and the resulting spectacle. This trend culminated in a statement on April 20 by the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) asking Aoun to comply with Oueidat’s decision “irrespective of whatever observations have been raised about its content”. Apparently, the SJC deems that Aoun must obey the cassation public prosecutor and execute his decisions even if they are illegal. The SJC thereby expressed a dangerous trend of subjecting the judiciary, which is supposed to be distinguished by its independence, to the military-inspired principle of “execute first and object later”. This stance was then parroted by a number of figures who accused Aoun of insubordination to her superiors’ orders and not complying with the obligation to obey!

Hence, Aoun’s challenge to this decision aims to give pause to all those who rushed to pass judgement and to set things straight by posing the following question: Is this decision, which many faulted her for disobeying, legal? If proven otherwise, would that not turn the perception of the roles of Aoun and Oueidat (along with the SJC) on their head by shifting the fault and the charge of breaking the law from the former to the latter? In that case, the fault would lie not in the insubordination to superiors’ orders, as some have perceived, but in the superiors’ exploitation of their influence to make unjust and illegal decisions. The fault would lie not in Aoun’s mutiny but in the obstruction of her work in order to conceal the truth. The fault would lie not in her decision to remove the door, but, first and foremost, in the act of locking it on her to the same end.

While we have not viewed Aoun’s petition, we can point out a series of legal violations, each of which is enough to destroy the decision’s legality.[2] Some, by virtue of their seriousness, render it as good as nonexistent. The most significant of these violations are the following:

- The decision encroaches on Aoun’s power as (appellate) public prosecutor in Mount Lebanon. Under Article 22 of the Judicial Judiciary Organization Law, the public prosecutor in each governorate is the one to head that governorate’s Public Prosecution office, administer its affairs, and oversee its employees, proper functioning, and by extension the distribution of work therein. The cassation public prosecutor has no legal power to supplant Aoun in this regard.

- The decision was akin to a punitive measure against Aoun for not attending an interview with the Cassation Public Prosecution concerning the complaint that chairman of the SGBL bank Antoun Sehnaoui had filed against her. This was confirmed by the SJC’s April 20 statement, which mentioned that Oueidat had intervened based on its request that measures be taken against Aoun for a list of behaviors, including her refusal to appear in relation to the aforementioned complaint. This is a violation because the cassation public prosecutor has no power to hand down punishments against any Public Prosecution judges. Rather, he may only refer the judge to the Judicial Inspection Authority for it to investigate and take the necessary measures.

- The decision essentially removed Aoun from a position she occupies under the judicial personnel charts decree as it stripped her of the power to investigate all important crimes (financial crimes, homicides, and drug trafficking) in the office that she heads. The cassation public prosecutor has no power to amend the judicial personnel charts, which are issued and amended only by decree pursuant to the principle of procedural consistency [parallélisme des formes].

- The decision was an interference aimed at obstructing Aoun’s work, as evidenced by the fact that she was served it while in the process of carrying out a judicial task and that the work distribution therein encompassed the cases that she is already investigating, not just future cases. In this regard, the decision was an exploitation of influence aimed at obstructing the execution of another judicial decision and therefore an abuse of authority and a crime under Article 371 and Article 376 of the Penal Code. The former punishes “any official who uses his power or influence, directly or indirectly, to obstruct… the execution of a judicial decision or memorandum or any order by a competent authority”. The latter punishes “any official who, in order to procure an advantage for himself or someone else… commits an act not provided for by law and contrary to the duties of his function”. Making this criminal interference worse, it completely contradicts the essence of the Cassation Public Prosecution’s powers, namely to ensure – rather than obstruct – the progress of criminal investigations and prosecutions in order to protect society’s rights.

While some who accused Aoun of mutiny and breaking the law based on her noncompliance with the decision could plead good faith, the SJC’s members cannot benefit from this excuse because of the seriousness of the violation, especially as the decision’s validity was debated inside the SJC, as indicated by the content of its statement. Hence, the SJC’s members may, on their part, also have committed an exploitation of influence aimed at obstructing judicial work in dereliction of the responsibility that the SJC exists to fulfil, namely to ensure the judiciary’ s independence and proper functioning.

There is one more question to address in this regard: Was Aoun obliged to execute the decision, even if it were illegal, pending its suspension or annulment by the competent judicial authority (the State Council)? This question stems from several French jurisprudential opinions contending that even in such cases, the decision should be effective until it is annulled by a judicial ruling or administrative decision in order to prevent practices of private justice. Though important, these opinions do not apply to this case because Aoun is the one with the power to distribute work within the Public Prosecution office that she heads and Oueidat’s decision required usurping these powers in the absence of any legal text. Hence, Aoun obviously has the right to disregard this decision as she is the only administrative authority authorized to make such decisions. Any other action would have led to the suspension of the investigation and loss of evidence and – most importantly – constituted negligence by Aoun in the exercise of her powers and performance of her duties.

This suit is clearly important for correcting the narratives about this case so that things can ultimately be set right. If the decision is found to be illegal, then everything said about Aoun’s mutiny and departure from the law was misplaced and – conversely – Oueidat and the SJC can be considered to have mutinied against the legal system and, most gravely, exploited influence to obstruct a judicial investigation in favor of the suspects in the money smuggling case.

A Watershed Suit for Reducing Hierarchical Authority

As previously explained, this suit’s importance transcends the money smuggling case as it also confronts the trend toward expanding hierarchy inside the Public Prosecution offices and, more broadly, inside the judiciary, which conflicts with the most important principles of judicial organization.

When the Code of Criminal Procedure was amended in 2001, Cassation Public Prosecutor Adnan Addoum managed to establish a hierarchy within the Public Prosecution offices that has no counterpart in other states that derive their juridical organization from the French system. This expanded the cassation public prosecutor’s latitude to control public right cases and interfere in the work of all Public Prosecution offices in a manner that generally accords with the ruling regime’s policies. Recently, Addoum’s successor Hatem Madi went so far as to describe the Public Prosecution offices as the policing and judicial arm of [executive] government.[3] Making matters worse, many cassation public prosecutors have not been content with their already-broad legal powers. Rather, they have endeavored to expand their hierarchical authority in a manner that conflicts with the law and undermines any balance in relationships inside the Public Prosecution and the safeguards on the exploitation of this authority, as the Legal Agenda has often warned. These figures include Oueidat, who – less than two weeks after his appointment to his current position (23 September 2019) – issued two circulars in this vein and ultimately issued the contested decision.

Three things render Aoun’s suit even more important:

- It may be the first of its kind in this regard, given the rarity of judges – particularly public prosecutors – disputing administrative decisions that judicial bodies issue regarding them.

- The hierarchical inclination that the suit targets is not limited to the cassation public prosecutor. Rather, it also encompasses the SJC, which went so far as to recognize the obligation of obedience and the principle of “execute first and object later”, as previously explained.

- The suit’s aim of reducing this hierarchy matches the grounds for the amendment to the organization of the Public Prosecution offices in the Legal Agenda’s bill on the independence and transparency of the judicial judiciary, which is still pending before Parliament’s Administration and Justice Committee.

So let’s keep watching.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] “Awwal ‘Ahd ‘Uwaydat ‘al-Amr Li”: Ta’miman Yuhaddidan Istiqlal al-Niyabat al-‘Amma wa-Juhud Mukafahat al-Fasad”, The Legal Agenda, 29 September 2019; Nizar Saghieh, “Superman Jadid fi al-‘Adliyya? (1) al-Haramiyya al-Mutlaqa wa-Shakhsanat al-Haqq al-‘Amm”, The Legal Agenda, 2 November 2019; and Nizar Saghieh, “Superman Jadid fi al-‘Adliyya? (2) al-Haramiyya Tusahhilu al-Iflat min al-‘Iqab”, The Legal Agenda, 4 November 2019.

[2] For more opinions in this area, see Issam Sleiman (former president of the Constitutional Council) and lawyers Paul Morcos (from the organization JUSTICIA) and Said Malek. They were interviewed by the LBCI program Nharkom Said on April 19 and April 23, respectively.

[3] Nharkom Said, 23 April 2021.