Churches in Egypt: Codifying Discrimination and Sectarianism

On August 30, 2016, the Egyptian Parliament approved the law on the construction and renovation of churches. Parliament thereby complied with Article 235 of the Egyptian Constitution, which stipulated the law’s issuance during the first parliamentary term.[1] Defenders of religious freedoms in Egypt opposed the law, arguing that it uses literary phrasing, violates fundamental rights recognized in the Constitution, and codifies discriminatory security and administrative practices.[2] While the Constitution’s inclusion of a text obligating Parliament to issue such a law may seem odd, it can be attributed to the recurrence of sectarian incidents stemming from opposition to the construction and renovation of churches in various areas. These incidents have been fueled by the absence of any actual legislation regulating said construction and renovation, and the continued operation of texts dating back to the Ottoman period.

Obsolete Texts and Discriminatory Security Requirements

Before the current law was issued, the construction and renovation of churches was subject to Hatt-i Humayun, a royal decree of Ottoman times. Istanbul issued this directive in 1856 to guarantee the religious rights of the sects and creeds of Ottoman subjects. The Egyptian 1923 Constitution stipulated that the laws and decrees issued before its promulgation remain in effect, and granted the king the power to regulate the officially recognized religions.[3] After the declaration of the [Egyptian] republic, this power passed to the president, who could then regulate the religious practices of followers of the religions recognized in Egypt and, subsequently, approve the construction of churches, monasteries, and other places of worship. The Ministry of Interior usually intervened in this decision by sending its approval or rejection to the President’s Office. In doing so, the ministry employed the conditions set by Deputy Ministry of Interior Azbi Basha in 1934.[4] These conditions center upon the church’s distance from the mosque or mausoleum, the faith of the area’s inhabitants, and whether the majority are Muslims, the amount of opposition to the construction, the number of Christians in the area, and the existence of another church in the township or the distance to the closest church beyond it. These questions clearly reflect the discrimination affecting the freedom of Christians to practice their religion, as no such questions are found in the decision that the Prime Minister’s Office issued in 2001 to regulate the construction of mosques.[5] This decision stipulated entirely technical conditions and required that the area be in need of the proposed mosque, but did not include any questions about the majority of the area’s inhabitants or conditions that take into account their sentiment should they be Christians.

Similarly, in a ruling issued on February 26, 2013, the Court of Administrative Justice settled the types of licenses that the church must obtain. The court found that there are two types of licenses. The first pertains to construction, renovation, demolition, or reconstruction, and is subject to the laws that regulate construction without any discrimination or prejudice to the principle of equality. The second pertains to the practice of the [religious] activity, and is issued via a decision that the president makes in accordance with the Hatt-i Humayun Decree. The ruling reflects the discrimination against Christian citizens; the court’s interpretation that the license issued by the president is for performing a religious activity within the church, monastery, or other place of worship implies that Christians in Egypt need permission to practice their religion. This contravenes the constitutionally stipulated principles of equality and citizenship. Mosques are subject to no such condition.

Given the above, we can conclude that Christians’ construction of churches and monasteries is subject to the discretion of the President’s Office. In practicing this discretion, the office relies on the opinion of the Ministry of Interior, which bases its submissions on its desire to take into account the Muslim inhabitants of the proposed church’s locality.

Sectarian Strife in Egypt’s Governorates

Before the revolution, the construction and renovation of churches often led to clashes between the Muslim and Christian inhabitants of an area. The incidents in October 2009 in Nazlet al-Badraman, a village in Minya Governorate, are but one example. A number of the village’s Muslims protested the renovation of the minaret of the village’s St. George Church, even though prior permission for the renovation had been obtained from the relevant authorities.[6]

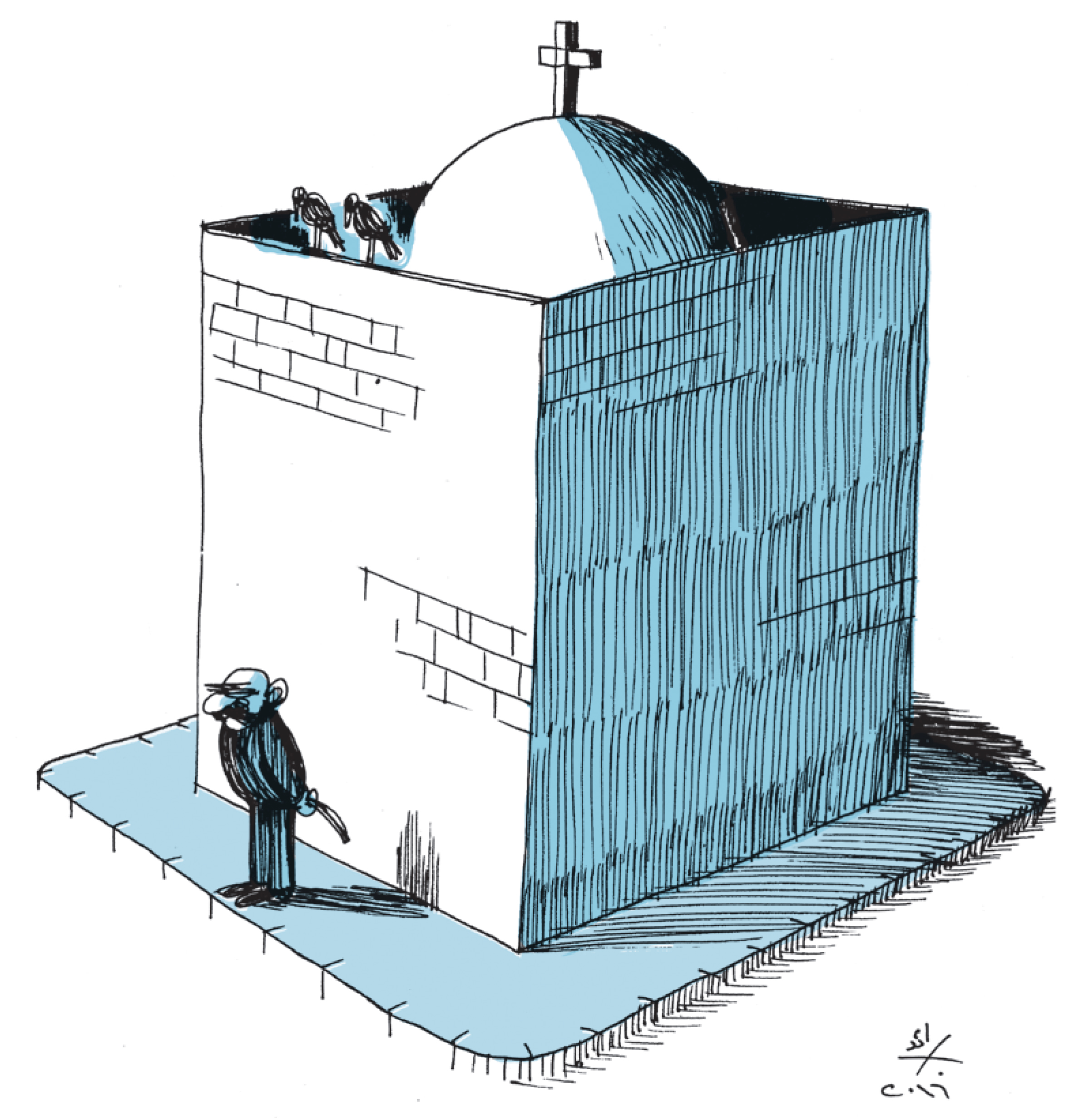

This trend continued after the revolution. One example is the incidents in October 2011 in Marinab, a village in Aswan Governorate. When the St. George Church was rebuilt, extremists objected to the presence of a bell, a minaret, and a cross atop the building, and demanded that the domes atop the concrete building be demolished. Although the church heeded these demands, hundreds of Muslims attacked it, lighting a fire within it and destroying the domes, walls, and parts of the concrete pillars without any interference from the security force present outside.[7] Likewise, in November 2012 extremists invaded lands belonging to the Diocese of Shoubra El-Kheima in Mantay in central Qalyub, in order to stop the completion of a Virgin Mary & St. Abanoub services building. Salafist leaders threatened to turn the church building into a mosque and prayers were actually conducted on the land over a period of two days.[8]

In these cases, the state usually acts as a bystander. The Ministry of Interior does not intervene to protect the churches; rather, the governor and the Ministry of Interior’s representatives in the area arrange reconciliation meetings [jalsa ‘urfiyyah] to resolve the problem without trying the aggressors. This practice provides a cover for sectarian incidents and spares their perpetrators from punishment.

At other times, the state also practices discrimination and violates the rights of Christians to practice their religion. For example, in November 2010 the construction of a church in the Talbiya area in Giza was halted. When the Christian citizens objected, the security forces dealt with them by force.[9] Similarly, in October 2009 the al-Khalifa district in Cairo demolished a services building of the St. Mina association in the al-Abagiya sub-district, claiming that the building was unlicensed.[10]

These examples reflect one of the forms of discrimination and persecution that Christians encounter when practicing their religion, and the transgressions to which churches and places of worship are subjected to because of the absence of a law regulating their construction, renovation, and expansion. To them can be added the state’s discretionary power over construction and renovation licenses, and the clear bias towards respecting the sentiment of Muslims instead of applying the law and guaranteeing the right of Christian citizens to practice their religion.

A Law is Needed, but what Law?

Given the above, there is clearly a need to regulate the construction of churches and to establish clear and specific rules for renovations and issuing permits, rules that are not subject to the discretion of the ّّPresident’s Office or the Ministry of Interior. There is also a need for rules that effectuate Christian citizens’ right to practice their religion without any encroachment by government or society, and to put them on par with Muslim citizens in this regard.

Hence, after the revolution, it was proposed that a unified law on places of worship be developed to guarantee equality in regard to the construction of such buildings, and to ensure the freedom to practice religion. In June 2011, the Cabinet proposed a unified bill on places of worship that gives governors or their deputies the right to issue licenses in their governorates. The bill retained the technical conditions and the requirements that there be a need for the place of worship and that the number of places of worship be proportional to the number of inhabitants, alongside other conditions and caveats. But the official Islamic institutions and the Islamic movements opposed the bill as they rejected putting mosque construction on par with the construction of places of worship for other religions. For example, the al-Azhar Sheikhdom expressed its opposition to a unified law and proposed merely issuing a law for the construction of churches, arguing that the construction of mosques is already regulated by the 2001 prime ministerial decision currently in force. The Salafist movement also objected to the unified law. Ultimately, this opposition led to a retreat from a unified law on places of worship, and to a discussion about a law on the construction of churches.[11]

The 2012 Constitution did not include any explicit text obligating the state to issue a law on the construction of churches. Rather, it merely stipulated freedom of belief and obligated the state to guarantee the freedom to practice religion and establish places of worship in accordance with the law;[12] this is most likely the case because the Muslim Brotherhood acquired the majority of seats in the constituent committee that drafted said Constitution, and the Church’s representative withdrew from this committee. As for the 2014 Constitution, it included an explicit text obligating Parliament to issue a law regulating the construction and renovation of churches so that Christians can practice their religion freely.[13] This provision can be attributed to the increase in sectarian attacks following the overthrow of the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as the desire for the Constitution to look like that of a civil state that guarantees rights and freedoms for all persons indiscriminately. On the other hand, by limiting the text to churches, the Committee of 50 that drafted the 2014 Constitution responded to the pressure imposed by the Islamic institutions and movements opposing a unified law on places of worship, siding with them at the expense of citizenship and equality. Thus, the committee bears a large part of the responsibility for codifying or even constitutionalizing the discrimination against Christians. Parliament followed the same course.

The Legislative Process: Respecting the Constitutional Time Limit at the Expense of Content

Parliament issued the law on constructing and renovating churches days before the end of its first term in order to respect the time limit stipulated in the Constitution. The law does not encompass monasteries; its first article stipulated the legislation of a separate law to regulate the status of monasteries, and the houses and places of worship therein. This indicates a narrow interpretation of Article 235 of the Constitution and limits the law to churches only. It also suggests a rush to issue a law on the construction and renovation of churches alone, instead of a law regulating [all of] the places of worship of at least Christians now that a unified law has been ruled out.

In August 2016, Parliament’s Constitutional and Legislative Affairs Committee began discussing the bill submitted by the Wafd Party. When the discussion returned to the proposal for a unified law on places of worship, some of the MPs objected, arguing that Article 235 of the Constitution clearly stipulates the issuance of a law specific to the construction of churches, and thus issuing a unified law on places of worship would contravene said article. The committee also revisited the Committee of 50’s discussions, wherein the Islamic institutions and movements had rejected this proposal on the basis that there is no need for a law on mosques.[14] Yet recent indications are that mosques are being built haphazardly, and that a law regulating their construction is seriously needed.[15]

At the same time, the government had for months been preparing a bill on the construction and renovation of churches. It consulted with representatives of the Egyptian churches to the exclusion of legal experts and civil society representatives. This decision can be attributed to the fact that the Church monopolizes the representation of Christians before the state as though they are its own subjects. This monopoly reflects the Church’s view of the law as a matter concerning clerics alone.[16] A climate of secrecy was also imposed over the discussions between the government and the Church’s representatives, so the bill was not put to social discussion. Similarly, the objections voiced by civil society organizations such as Egyptians Against Religious Discrimination, the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, and the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights were not heeded. The last of the three launched the “Closed for Security Reasons” campaign to raise awareness of the problems associated with constructing and renovating churches and their connection to the sectarian incidents, and proposed the criteria that the law should include.[17]

On August 27, 2016, the government sent the law to Parliament. It was debated and passed just three days later, which reflects obvious haste in debating the law and a desire to issue it within the first parliamentary term pursuant to the Constitution, without any real regard for its content.

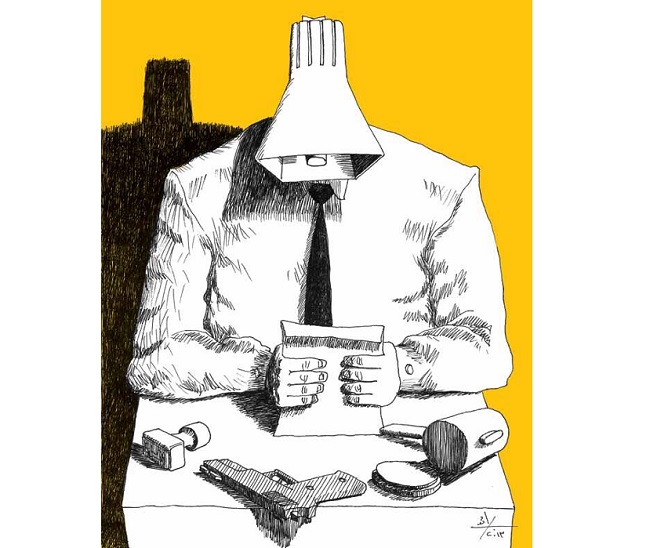

Some MPs objected to the law’s articles within the joint committee, composed of the Committee on Religious Affairs and Awqaf, the Committee on Constitutional and Legislative Affairs, the Committee on Local Administration, the Committee on Culture and Media, the Committee on Antiquities, and the Committee on Housing, Public Utilities, and Construction. These MPs argued that the bill infringes the principle of citizenship and is unconstitutional. Some also felt that the law bears the clear fingerprints of State Security officers.[18] Despite these objections, the law was approved by the joint committee and then promulgated in the General Assembly via a two-thirds majority of MPs. According to Parliament’s speaker, the law’s special nature meant that there was no scope for amending what the Church had approved, and there was no reason to issue a law approved by Parliament but rejected by the Church.[19] This suggests that the state treats Christian citizens on the basis that they are a sect represented exclusively by the Church and that the Church alone has the final word on everything concerning their affairs. Such treatment entrenches sectarianism and discrimination against them, and infringes the principle of citizenship.

The law was issued amid overwhelming opposition from civil society organizations and defenders of religious freedoms. They objected to the law’s definitions of churches, the obligation to wall in the church, and the fact that the law does not specify the approvals needed for constructing, renovating, or rebuilding a church.[20] They also objected to the lack of clear legal criteria in the law’s articles and the reliance on literary language.[21] Because of all of these issues, the law does not provide satisfactory solutions to the current situation. Instead, it contains serious problems relating to licenses and implementation and does not properly effectuate the freedom of Christians to practice their religion.

The legislative process through which this law was issued reflects several issues: the failure of the government and Parliament to handle the issue of the construction and renovation of churches, the debasement of Christian’s freedom to practice their religion, and the downplaying of the sectarian incidents occurring as a result of the infringement of this right and the neglect to protect it legally. It also clearly reflects the state’s bias towards treating Christians as a “minority” or “sect”, as the law refers to them,[22] and not as citizens with the same rights as their Muslim counterparts. By doing so, the state distances itself from the concept of a state based on citizenship and equality.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] Article 235 of the Egyptian Constitution stipulates that: “In its first legislative term after this Constitution comes into effect, the House of Representatives shall issue a law to regulate the construction and renovation of churches, guaranteeing Christians the freedom to practice their religious rites.”

[2] See: “Reproducing the Status Quo: New Church Construction Law Consolidates Discriminatory State Policies and Confiscates Citizenship Rights of Future Generations”, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, August 31, 2016.

[3] See: “License to Pray: The Crisis of the Freedom to Adopt Places of Worship in Egypt”, a study issued by the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, December 2014.

[4] See: “Places of Worship: Between the Hamayouni Decree and the Ten Conditions…and Ending with the Law on Constructing Churches”, DotMsr, August 28, 2016.

[5] For more on this topic see the official website of the Egyptian Ministry of Awqaf.

[6] See: “Freedom of Religion and Belief in Egypt Quarterly Report, Oct – Dec 2009”, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, January 2010.

[7] See: “The Marinab Incidents: A Flagrant Example of the State’s Bias Towards Intolerance”, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, October 4, 2011.

[8] See: “Against the Backdrop of the Invasion of the Land of the Diocese of Shoubra El-Kheima, the Egyptian Initiative [Says]: The President of the Republic Must Immediately Begin a Social Discussion for the Sake of Issuing a Just Law on Places of Worship”, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, November 8, 2012.

[9] See: “EIPR Condemns Security Violence against Coptic Demonstrators…The Public Prosecutor Must Prosecute the Security Personnel Responsible for the Death of One Christian and the Injury of Dozens More in Omraniya”, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, November 24, 2010.

[10] See: “Freedom of Religion and Belief in Egypt”, op. cit.

[11] See: “License to Pray”, op. cit.

[12] Article 43 of the 2012 Constitution stipulates that: “Freedom of belief shall be protected. The state shall guarantee the freedom to practice religious rites and to establish places of worship for the divine religions as regulated by law.”

[13] Article 235 of the Egyptian Constitution, op. cit.

[14] See: Abd al-Gani Diyab’s, “A Unified Law on Places of Worship: The Constitution Prohibits and Parliament Proposes”, Masr Alarabia, August 16, 2016.

[15] See: Abd al-Wahhab Isa’s, “Experts: The Absence of a Law on Building Mosques Has Led to Their Haphazard Construction”, ElWatan News, July 20, 2016.

[16] See: Ishak Ibrahim’s, “Constructing Churches: The Treasure Is in the Battle and Not in the Law”, Mada Masr, September 4, 2016.

[17] For more information see the campaign’s Facebook page.

[18] See: Mohamed Hamama’s, “After 150-Year Wait, Parliament Passes Church Construction Law in 3 Days”, Mada Masr, August 30, 2016.

[19] See: Abd al-Latif Sabah’s, “Abdel Aal: Churches Law Has Special Nature and If We Approve It and the Church Rejects It Then There is No Reason to Issue it”, Parlmany, August 30, 2016.

[20] See: “Reproducing the Status Quo”, op. cit.

[21] See: Mohamed Adel Souliman’s, “Observations on the Law on Constructing Churches: Literary Phrasing and Actual Seizure”, The Legal Agenda, September 2, 2016.

[22] For example, the law’s first Article stipulates: “1 – The church: a free-standing building that may be topped by one or more domes and wherein the prayers and religious rites of the Christian sects are performed” and “6 – The relevant religious head: the top religious head of the Christian sect recognized in the Arab Republic of Egypt.”