Military Trials in Egypt: Where is the Swift and Certain Justice?

A military court has delayed its ruling in the case of the Alexandria Shipping Company until October 18, 2016. Twenty-six workers, of whom 14 are being detained pending the ruling, stand accused. This is the fourth postponement of the court’s ruling on this lawsuit, which had previously been pushed back to August 2nd, August 16th, and, most recently, September 18th of this year. These delays prompt questions about claims that officials of the military courts have repeated for the past six years; that military trials are an accepted means of deterrence both among the public at large and at the level of the individual, due to the speed with which they rule on the cases brought before them.

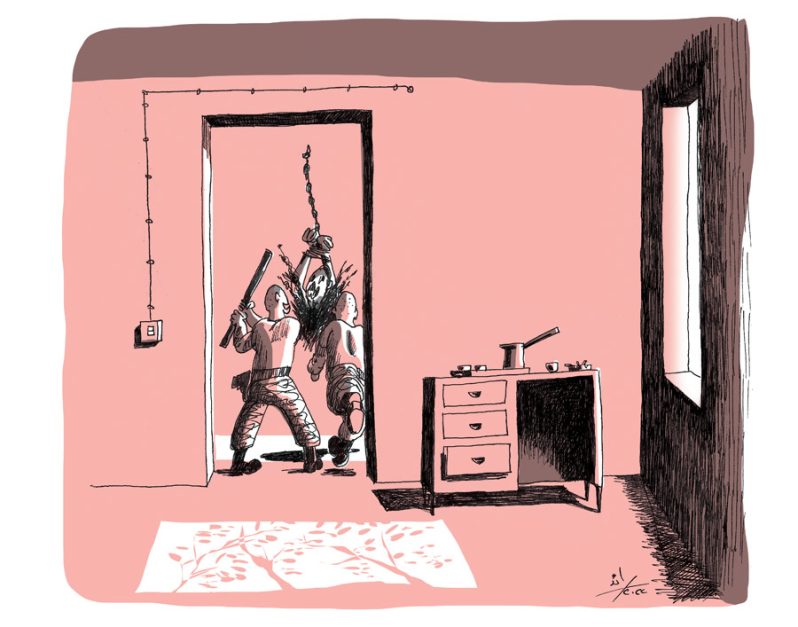

The Threat of Punishment Ensures Good Behaviour

“He who does not fear punishment behaves badly.” Major General Medhat Ghazi, president of the military judicial division, repeated this statement while discussing the importance of military courts to protecting the Egyptian state from terrorist-designated threats in the 1990s. On December 1st, 2013, he was speaking in an interview with media personality Lamis Elhadidy, affirming the idea that the speed of these court rulings made them effective as a deterrent for both individuals and the public.[1] According to the major general, this is what society wants. A former deputy in the military judiciary, Major General Taha Sayed Taha, expressed the same point of view, explaining that prompt punishment translates to a general deterrence, because society remembers the crime and the identity of the perpetrator at the time that the punishment is enforced; whereas, the opposite occurs when a ruling is issued five years after a crime is committed. Taha invoked the slogan of the military courts: “swift and certain justice.” As an example, he explained that a case that might take three to four years in regular courts might be decided in 100 hours, and only a month or two in a military trial.[2]

Commenting on the expansion of the military courts’ practice of trying civilians, Major General Ghazi cited the number of civilians referred to military courts in 2009 and 2010 as evidence of the limited nature of the practice: [in those two years,] 724 civilians were tried in military courts, of whom 128 were charged with falsification for the purpose of avoiding military service. This leaves 596 civilians who were tried in military courts in cases related to attacks on military facilities, equipment, and personnel over the course of two full years.

Today, over two years have passed since the adoption of a constitution that permits trying civilians as military personnel, in cases related to facilities and members of the armed forces, and the passage of a law that places public buildings and facilities under military protection. It seems an apt time to evaluate the military judiciary’s role, and their choice of slogan (“justice, swift and certain”), and the extent of its effectiveness over the past two years.

Legal Expansion of the Use of Military Courts

Once the new Egyptian Constitution of January 2014 authorized trying civilians in military courts, there was no going back. On October 27, 2014, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi issued a legislative decree stipulating that “the Armed Forces, with the assistance and full coordination of the police and in full coordination, will assume responsibility for securing and protecting public and vital buildings, whether sites or networks of electrical towers, gas lines and oil fields, railroads, and major road and bridge networks, among other installations and facilities that are public property, and which now fall under military control. These are considered as military-protected facilities throughout the period of security and protection.”[3]

According to this legislative decree, crimes taking place in these kinds of installations and facilities, or on public property, are subject to the jurisdiction of military courts. It also requires that the public prosecutor refer these cases to a military prosecutor.[4] The law has led to a huge expansion of referrals of civilians to military courts; by way of illustration, it suffices to note the number of civilians transferred to military courts in the Minya governorate, as reported in the daily Egyptian press.[5] From the 17th to the 21st of September 2016, military courts there heard cases trying 898 civilians in Minya.[6] This number exceeds the number of civilians tried before military courts in 2009 and 2010 in the entire country.

According to a report issued by the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression last February, a total of 46 university students have been tried before military courts.[7] Additionally, the group “No to Military Trials for Civilians” noted 3,000 such cases, of which 300 concerned students and 22 young women. These do not even include trials that interested parties were not able to attend, according to the group’s report, announced at a press conference in March 2015.[8] This figure covers only the period from October 27, 2014 through the issuing of the report – that is, only the first five months following the implementation of the decree on the security of public places. These numbers are the most significant evidence contradicting the statements made by military court officials, regarding the limited number of civilians being transferred to military courts.

Retroactive Jurisdiction

On August 12, 2014 –before the legislative decree placing public places under military protection was issued in October 2014– a minor was arrested outside of his home in the governorate of Menofia. He was taken to the police station, where a report was made of the incident. On the following day he, along with others, appeared before the district prosecutor, and faced a number of charges including membership in a prohibited organization, assembly, protesting without a permit, use of force, violence and threats of force and violence, and shouting expressions against the armed forces, and sabotage of public property.

The public prosecutor decided to remand the minor and the others charged. Subsequently, the appeals prosecutor decided to transfer their case to the North Cairo military prosecutor, in accordance with the decree on military protection of public places. On November 30, 2014, the military prosecutor decided to try the minor and the others to the military’s criminal court in North Cairo as case 319/2014; the minor was given a 15-year prison sentence.

This child’s case was not the only one in which military courts violated the principles of its jurisdiction by enforcing laws retroactively. The hundreds of civilians referred to above who were tried in Minya were transferred to military courts over a year before the legislative decree on military protection of public places went into effect. While the decree was issued in October 2014, most of them were tried for crimes related to the dispersal of the Rabaa sit-in in August 2013.

In trying these cases, the military prosecutor has committed a grave breach of the Constitution. Article 95 of the Egyptian Constitution specifies that, “there shall be no crime or punishment except pursuant to a law, and a penalty may only be inflicted by a court judgment. Penalty shall only be imposed for acts committed after the effective date of the law imposing it”. While errors made by public or military prosecutors when enforcing laws may be understandable, constitutional violations committed by those sitting on the judicial bench are not. These errors in matters of procedure invalidates their rulings.

The Lie of a Speedy Trial: Delaying Sentencing as a Strategy for Dealing with Public Opinion

Postponing sentencing in the case of the Alexandria Shipyard workers, which has now happened for the fourth time, is not the first time that military courts have delayed pronouncing a ruling. The same thing happened with the case of the “advanced operations cell” (the case referred to above), in which sentencing was first deferred on March 13, then April 3, then April 24; it was not until May 29, 2016, that the ruling was issued, in the court’s fourth session.

It appears that in these two cases, the military courts’ actions reflect a new approach to dealing with cases that gain public scrutiny; they attempt to prolong litigation until media attention dies down around high-visibility cases. They issue their ruling only after advocacy campaigns on behalf of the accused have completely subsided, and attention has been redirected elsewhere.

Looking at the case of the Alexandria Shipyard workers, for example, we find that it has preoccupied public opinion, as the trial has taken place against a background of the workers protesting the violation of their financial rights. Likewise, the “advanced operations cell” case came into public view upon the sentencing of a young man with no record of political activity. He was arrested while eating dinner with friends, which prompted his family to launch a campaign for his release.[9].

The majority of those who have been subject to enforced disappearances for various periods of time have found public opinion to be supportive of them, demanding that they be tried before a regular court. This has prompted the [military] courts to adopt the tactic they are now taking with the Alexandria Shipyard workers; extending the trial before pronouncing a ruling, and issuing a harsh verdict should media interest wane. We fear this is what will happen with the Alexandria Shipyard workers.

It is worth pointing out that in delaying its verdict more than three times, the military court is violating Egyptian procedural law, which organizes the authority of the courts when it comes to delaying rulings. The law states that, “if it is necessary to postpone sentencing for a second time, the court must clarify this in a session specifying the day that the ruling will be announced, and stating the reasons for the delay in the record of the session and in its report; it may not subsequently delay ruling more than once”.[10]

The facts of these cases refute the slogans that the generals are peddling about military trials. How is this “swift and certain” justice?

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_1GY2CuUNQM

[2] See the website Bawabat al-ʿAsama, August 14, 2015.

[3] Text of the first Article of legislative Decree No. 136 of 2014 on military protection of public places.

[4] Second Article of legislative Decree No. 136 of 2014 on military protection of public places.

[5] Minya is located in the northern part of Upper Egypt, and is 500 km from Cairo.

[6] According to the daily press, the military court in Minya was in session from September 17-21, 2016: see

http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/1010028 http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/1010342; also, see http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/1011180 http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/1012038.

[7] See: “Legal Commentary and Survey of Cases: Trying students as military personnel eliminates the guarantees of a fair trial”, issued by the Institute for Freedom of Thought and Expression,

[8] Fourth press conference of the campaign “No to Military Trials…”: 2,000 cases in 5 months.

[9] See Facebook page: “Free Omar Mohamed Ali”, demanding his release,

[10] Article 172 of the Civil and Commercial Procedure Code, No. 13 of 1968.