Tunisia: From a Police State to a State of Police Unions?

The issue of police unions has come to the forefront of political and rights debate after every dangerous transgression that they commit, particularly against the three branches of government. In February 2016, one union besieged the Prime Minister’s Office in Kasbah to pressure it to meet material demands. Similarly, in November 2017, the largest police force unions issued a joint statement threatening MPs and politicians with withholding protection if they did not approve the bill to deter attacks on police within two weeks. However, the most dangerous transgression occurred in February 2018, when two of the most representative unions besieged the Ben Arous court while it examined torture charges against some officers. The unions repeated this action in October 2020 to pressure the investigating judge in another case.

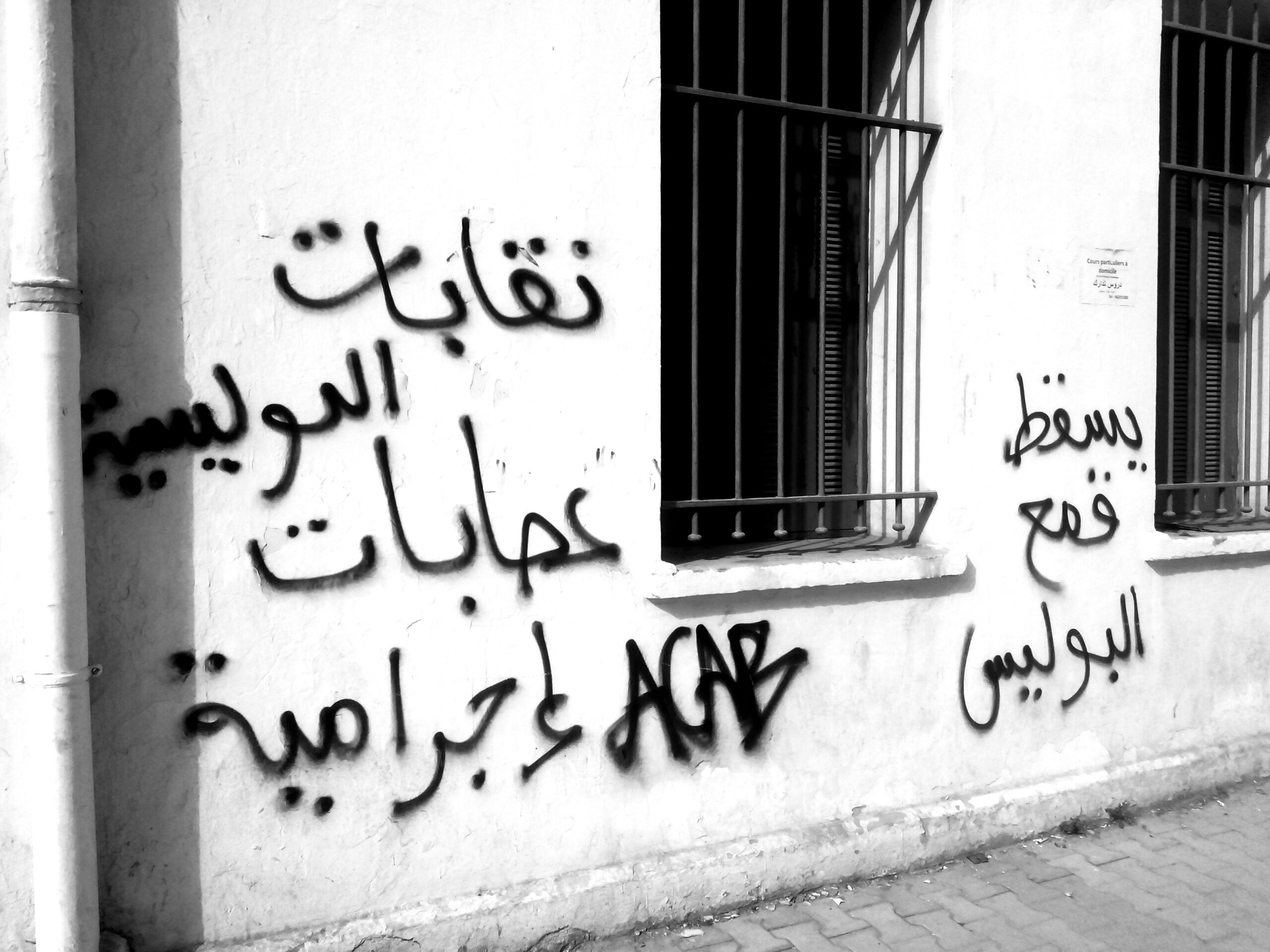

This time, the debate reemerged after several police unions issued a succession of statements clearly threatening protesters, declaring a ban on demonstrations in Habib Bourguiba Avenue, and calling upon officers not to comply with their leaderships’ instructions to exercise restraint toward demonstrators. Some unions even declared a days-long suspension of administrative services. These statements were followed by field protests. The most prominent occurred in Sfax governorate, where unionists chanted excommunicating slogans before attacking a vigil held by rights activists and families of youth detained in the recent protests, and trying to run them over with police vehicles. These dangerous excesses came in response to what the unions deemed an “impingement on the dignity of police” during a demonstration on January 30, where demonstrators threw balloons filled with white and colored paint at the police barricading their advance in Habib Bourguiba Avenue.

Unprecedented, Unbridled Repression… Because of a Few Photos from a Demonstration

On the evening of January 30, hundreds of demonstrators, mostly youth, gathered to support the protests of underprivileged neighborhoods and condemn the repression that they had faced. This resulted in over 1,600 arrests and the death of the youth Haykel Rachdi after he was hit by a teargas canister. The slogans targeted not only Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi and his political bloc but also the security apparatus, which bears responsibility in the field for the many transgressions occurring. Facing the police barricade in Habib Bourguiba Avenue, some of the protesting youth resorted to methods unfamiliar in Tunisia and inspired by protest movements around the world, such as throwing paint balloons at police and using their shields to apply lipstick.

Amidst broad international and domestic criticism of the government’s response to the protests, police officers received instructions that emphasized restraint and not using force… in front of the media’s cameras. The government’s strategy for confronting the protests came to be based on closing as many ingresses into the site of the demonstration as possible and waiting for the number of demonstrators to fall and for journalists and their cameras to leave before beginning the arrests. Although restraint from the armed party representing the state when handling “provocations” by peaceful protesters is a given in any democracy, photos of the demonstration prompted a wave of solidarity with the security forces, which the unions exploited to launch protest movements in the name of protecting “the dignity of police personnel”.

Various national and regional police unions issued a succession of statements announcing innumerable actions. These statements clearly threatened that protesters would be prosecuted and future demonstrations repressed, regardless of instructions from leaderships. The police unions also targeted civil society organizations supporting the protests. It focused on the Tunisian Human Rights League and associations defending LGBTQ+ rights, with anti-human rights slogans excommunicating them and portraying them as traitors.

The police unionists did not stop at dangerous slogans. Rather, they used their social media pages and groups to incite against the activists, spread their pictures and personal details, and call for officers to retaliate against them, which is what eventually occurred. Barely a day passes without activists who participated in the marches, including officials in the student union, rights associations, and left-wing political parties, being arrested. The arrests also included queer activists who participated in the demonstrations. Most of the arrests have resembled abductions: the subjects were monitored and intercepted without any judicial warrant, they were violently assaulted either at the police stations or in isolated places, their presence at the police stations was denied so that lawyers could not access them, and then they were released. One of the protesters who was abducted and abused reported that the officers who attacked him repeatedly said, “You want to dissolve us?”, in reference to the demand to dissolve police unions.

The police unions’ brutality was not limited to activists; rather, they also threatened the media. The website Al Qatiba relayed testimonies that “in the days following the famous Saturday march, police unionists called a number of directors and editors-in-chief of press organizations to threaten them with harassing their journalists, preventing them from working in the field, and retaliating against them should they criticize the police and police unions”.

All these grave violations of rights and freedoms evoked no deterring response from Prime Minister and Acting Minister of Interior Hichem Mechichi. Instead, he provided them with political cover. He received the police unions, expressed his understanding of the police’s anger, and promised to respond to their occupational demands in an attempt to placate them and discourage them from further protest.

Union Multiplicity: “Democratizing Repression” Instead of Democratizing the Security Apparatus?

In contrast to the political cover that the prime minister afforded to the police unions’ transgressions and the repression of the protests, some interpreted the position of President Kais Saied, particularly when he appeared in Habib Bourguiba Avenue surrounded by passers-by before entering the Ministry of Interior, as supportive of the right to demonstrate in this street. However, Saied’s comments in the ministry did not address the police unions’ transgressions and merely called on them to unite into one union.

Although weak, the president’s stance did illuminate one cause of the runaway activity of police unions in Tunisia, namely their remarkable multiplicity. Within a few months of the May 2011 decree permitting police to organize into unions, more than 100 base-level unions emerged for different units and regions.[1] Although some bodies emerged combining a number of unions and aspiring to represent all the security forces, the base unions maintained much independence from the center. This independence was reflected recently when a number of local and sectoral unions issued, without the cover of centralized representation, their own statements on the January 30 demonstration and took actions individually, as occurred in Sfax, Monastir, and Tunis.

This independence may be reinforced by competition among the major bodies, specifically the Syndicate of Officials of the General Directorate of the Intervention Units (SFDGUI), the National Union of Syndicates of Tunisian Security Forces (UNSFST), and the National Syndicate of Internal Security Forces (SNFSI), to represent all security forces. This competition thwarted various attempts to unite the unions into one umbrella body and encouraged them to try to outdo one another and adopt maximalism. It also prompted the national-level unions to remain silent about their members’ and bodies’ transgressions for fear of losing them to a competing organization.

Besides successive governments’ failure to reform the security apparatus and regulate union activity within it, several other factors have contributed to this surge of unions. One such factor is that some general directors, who fear exclusion with every transfer of power, use the unions to fortify their positions.[2]

Similarly, the police unions, which consider themselves part of “civil society”, have become an accredited partner of some domestic and international organizations in projects to “reform the security sector”. This status provides privileges and opportunities for the unionists. The most prominent of these projects include “community-oriented policing”, which brought the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the two largest police unions[3] together and ran from 2013 to 2019 with a budget surpassing USD 10 million.[4] Yet this enormous funding did not contribute to any significant change in policing methods. Instead, the police unions managed to impose their concept of “republican security”. This vision is based on two components: achieving the highest level of independence from political authority (thereby obstructing any democratic oversight over the Ministry of Interior), and improving the image of police work without affecting its priorities or methods.[5]

Finally, the union surge contributed to the fragmentation of the security apparatus and the creation of many centers of influence within it, some of them linked by clientelist relationships to business owners, according to testimonies from inside it.[6] This resulted in reducing the formal, centralized subordination to the political authority in favor of new, disparate and undisclosed subordination to capital.[7] The multiplicity of relationships and allegiances obstructs any move toward uniting the organizations into one central apparatus and further fragments the security establishment, especially as the political authority is weak and unable to impose discipline in the Ministry of Interior or effect accountability for any deviation from the law or regulations.

The police unions exploited this weakness to go beyond sectoral demands and interfere in policing decisions, ultimately inciting their members to disregard the instructions to exercise restraint toward demonstrators. Photos and testimonies from the February 6 demonstration showed police leaders trying to prevent lower-ranking officers from attacking lawyers and struggling to impose discipline.

The situation is further complicated by the police unions’ success, while competing to outdo each other’s demands, in destabilizing the police hierarchy. This occurred via the fulfillment of their demand that the highest rank an officer reaches also be granted to all other officers in the same graduating class, such that promotion no longer depends on academic qualifications or continuous training courses.[8] This bizarre concession only increased officers’ anger and frustration because of the shortage of positions appropriate for these mass promotions. Hence, “career regularization” remains the unions’ foremost demand.

In sum, the police unions have helped to dismantle the chain of command and weaken discipline within the ranks of the security forces. Likewise, they have helped to democratize repression by freeing the decision to use it from the monopoly of the head of the political hierarchy and putting it in the hands of many actors both within the police establishment and even outside it via clientelist relationships.

At the same time, the unions have played a large role in obstructing any progress toward democratizing the security apparatus in the sense of subjecting it to democratic oversight and making it protect the rights of people and society (instead of terrorizing them) and impose the law both internally and externally. Despite the passage of a decade since the revolution and all the foreign funding allocated, very little has been achieved in this area.

Police Unions: Shielding Police from Any Oversight or Accountability

Despite all the gains that the revolution has achieved in terms of rights and freedoms, it has failed to defang the police and subject it to democratic oversight. Rather, it further fortified the police and increased their derivation of power through arms. The nonaccountability and impunity of officers is epitomized by the sight of police unionists besieging courts examining torture cases but is not limited to the judiciary; rather, it encompasses all levels of oversight.

In the months following the revolution, Minister of Interior Farhat Rajhi dissolved the Higher Inspectorate for Internal Security Forces and Customs Services, which, despite its shortcomings, was akin to the “the police’s police”.[9] However, it was not replaced with any counterpart. Furthermore, the project to reform the Ministry of Interior, which minister Lazhar Akremi was charged with drafting as part of a ‘white paper’, remained ink on paper. The successive governments disregarded it for various reasons, including the lack of political will, the emergence of the threat of terrorism, and the police unions’ resistance to any reform that could make officers accountable. This resistance extended to the proposal to draft a code of conduct regulating police work as part of the UNDP’s community-oriented policing project, which the SNFSI opposed despite its participation in the project.[10]

Although a governmental order in 2017 established – in place of the Higher Inspectorate for Internal Security Forces and Customs Services – a central inspectorate enjoying a broader purview and greater capabilities,[11] its functions center more on monitoring administrative and financial conduct than pursuing violations of rights and freedoms. Not even the establishment of a new administration concerned with human rights via the same order fills this void, as its functions are predominantly advisory and it seems more like a front for attracting funding than an effective body. Moreover, internal oversight, especially in security agencies, has intrinsic limitations, and the unions vehemently defend their officers and provide cover for their transgressions.

The same goes for external oversight. The constitutional Human Rights Commission, which enjoys significant powers to investigate violations of human rights and freedoms and whose law allows it to conduct surprise visits to detention and arrest facilities, is still waiting for Parliament to elect its members. The role of the Anti-Torture Commission, on the other hand, is limited by its purview and capabilities. While it is important that several bodies possess investigation powers enabling them to access detention facilities, they are no substitute for a body specialized in pursuing transgressions by police personnel, provided that it is independent of the Ministry of Interior and has all the necessary powers.

As for judicial accountability, the vast majority of complaints never get past the investigation stage. Many means are used to block the complaints or erase evidence, so very few cases reach the judgment stage. When they do, the unions resort to flexing their muscle in front of the judiciary and pressuring it using state force, as occurred in 2018 at the Ben Arous court and in 2014 at the Sousse 2 court, which the police unions blockaded for three days.

The latest transgressions by police unions show once again that the unionists have internalized the sense that they are above accountability. On the other hand, by filing a criminal complaint against the regional internal security forces union in Sfax, the Tunisian Human Rights League appears to be attempting to charge the judiciary with its responsibility in deterring these efforts to overpower the law through force of arms. The slogan, “We’ll prosecute them, try them, and hold them accountable”, which was taken from a speech by the martyr Chokri Belaid and has recently been widely used against the police unions in particular, expresses the same sentiment.

It is true that the existence of unions in the security services is not a Tunisian innovation, and that even in other democracies, they by nature encourage impunity, either collectively by opposing reforms that subject police work to oversight or individually by protecting embroiled officers from accountability.[12] However, the police unions in Tunisia act as though all means, including striking, which the law prohibits, are legitimate for the sake of obtaining their demands. They do not hesitate to use the means, powers, and arms that the state monopolizes for their own ends. Hence, the police unions, which arose by virtue of the revolution, have become a barrier to any reform of the security system, which has largely retained its old methods except for falling in line with centralized decisions.

Irrespective of our position on the principle of police union activity, which is allowed under Article 36 of the Constitution, dissolving the police unions embroiled in blatant and grave transgressions appears to be an unavoidable first step for constructing a democratic and responsible policing system. This reform, which could occur in a participatory manner that involves listening to officers’ views and concerns, could also include regulating union activity and clearly defining the methods that may not be used, the areas that fall outside the scope of union activism, and the punishments that await violators. Otherwise, the revolution – whose tenth anniversary we are commemorating – will have merely replaced a police state with a “police unions state”, despite all its gains in terms of rights and freedoms.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] Sharan Grewal, “Time to Rein in Tunisia’s Police Unions”, POMED, 29 March 2018, p. 2.

[2] International Crisis Group, “Réforme et stratégie sécuritaire en Tunisie”, Middle East & North Africa Report no. 161, 23 July 2015, p. 10.

[3] The SFDGUI and the SNFSI.

[4] Audrey Pluta, “Pas de révolution pour la police ? Syndicats et organisations internationales autour de la « Réforme du secteur de la sécurité » en Tunisie après 2011”, Lien social et Politiques, is. 84, 2020, p. 122-141.

[5] Ibid.

[6] International Crisis Group, op. cit., p. 11.

[7] Ibid.

[8] International Crisis Group, op. cit., p. 7. These exceptional promotions were adopted via Article 52 of the Supplemental Finance Law of 2014 and Order no. 3632 of 2014, dated 30 September 2014, on approving the promotion lists produced in accordance with the career regulation criteria for officers of the National Security and National Police Corps, National Guard Corps, and Civil Protection Corps for 2014.

[9] Pluta, op. cit., p. 135.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Governmental Order no. 737 of 2017, dated 9 June 2017, on amending Order no. 543 of 1991, dated 1 April 1991, on the structure of the Ministry of Interior.

[12] Benjamin Levin, “What’s Wrong With Police Unions?”, Columbia Law Review, vol. 120, is. 5, p. 1340.