The Risks of Pathologizing Syrian Refugees: Towards a Collective Social Suffering Approach

The conflict in Syria has become a humanitarian and public health catastrophe. Thousands of Syrians are forced to flee their homes under the threat of persecution, conflict and violence. By January 2014, over 800 thousand Syrian Refugees were registered at the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR). This brings the estimated total of the number of registered and non-registered refugees to about a million.[1] A special report issued by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) shows that the registration process in itself is problematic. Forty-one percent of the interviewees in the survey said they were not registered because they lacked information on how and where to go to register, or because the designated locations to register were too far.[2]

Health care (including primary and mental health care) is one of the fundamental pillars in an emergency humanitarian response. To be fair, one should note that the humanitarian response and its efficiency is a complicated affair and cannot be reduced to UNHCR operations. The Lebanese government and various ministries are also involved. This is why the following commentary is not meant as a wholesale criticism. It is based on my personal experience in the field, reports from the refugees I met, as well as a variety of published research, including the MSF report for 2013[3] and reports of public health professionals.[4][5][6]

Access to Health Care for Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: Challenges and Gaps

For registered and non-registered refugees alike, access to assistance seems challenging and complicated. Among registered Syrian refugees, the MSF survey mentioned above found many complaints. Roughly one in four said they had not received any assistance, while 65% said they had received only partial assistance that did not cover the families’ needs.[7] The donor funds received from foreign governments seem to be either insufficient, or inadequately organized and distributed in light of the overwhelming demand for humanitarian assistance -especially in the health sector.

The living conditions of many Syrian refugees in Lebanon are tragic and precarious. Many refugees live in extremely poor, overcrowded and unsanitary conditions.[8] Their health is thus quickly deteriorating. Lebanese doctors operating in mobile clinics established by international and local NGOs report rising incidences of tuberculosis, skin diseases (i.e., scabies and skin infections), hepatitis, digestive and respiratory diseases, and other contagious diseases.[9] There are few resources available to adequately treat chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, epilepsy), or to provide antenatal or postnatal care. For people with cancer, no services or treatments exist.[10] Furthermore, most children lack basic vaccinations and are at a high risk of developing severe malnutrition and growth delay.[11] Unofficial filed reports indicate that many children have died from malnutrition and cold, especially during the winter storms. Another issue is the rise of gender-based violence, notably cases of women rape, with no access available to life saving treatment and care to combat sexually transmitted diseases including HIV.[12]

The UNHCR coordinates support with relevant ministries and NGOs, but these services remain modest compared to the needs of the Syrian displaced population. Access to health care seems to be one of the biggest concerns for Syrian refugees in Lebanon, especially since UNHCR significantly reduced their health care and shelter services due to a lack of funding.[13] Hospitals that receive displaced Syrians often lack basic equipment and medical teams appear overwhelmed by this inflow of patients and by medical conditions they are not all familiar or trained to deal with.[14]

Mental Health in Emergency Setting: The Controversy of Trauma-Focused Services

In a resource-poor country like Lebanon, mental health care is yet another important aspect of healthcare provision in the context of humanitarian emergencies arising out of conflict. Programs based on trauma-focused services and on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)[15] screening and management, are being increasingly provided by foreign donors. However, these programs have been the subject of controversy. Some experts see the PTSD category as a western construct that is not particularly relevant in non-western societies, and others consider denial of the importance of traumatic stress a professional error.[16]

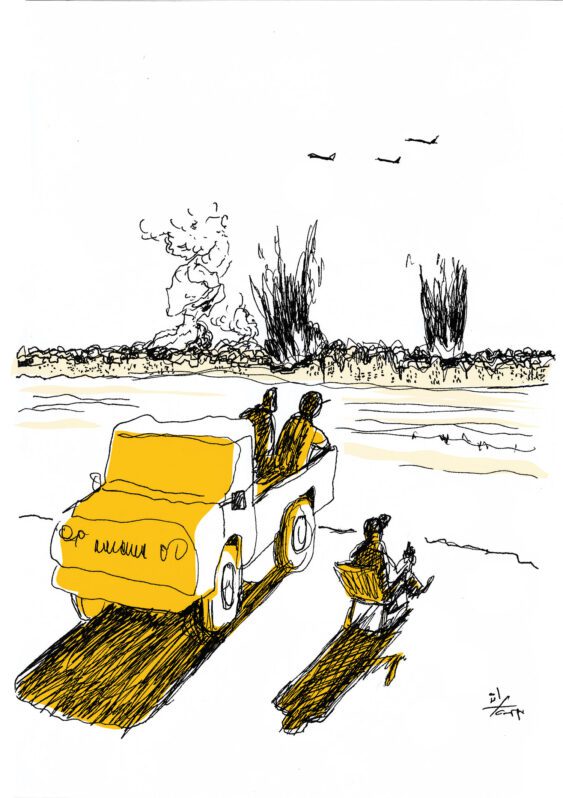

This debate has emerged at a time when a particular paradigm has become the dominant one through which contemporary refugees are seen. The trauma paradigm that originated in the US and places focus on PTSD has replaced the political paradigm when dealing with refugees in all cultural settings. This has led to a surge in international funds for emergency mental health programs. Conceiving of refugees in general, and Syrian refugees in particular, as traumatized medical “patients” suffering from a clinical disorder, has become one of the main means by which a refugee can access asylum and resettlement in a third country through UNHCR. A psychiatrist’s report stating that the “patient” suffers from severe PTSD due to traumatic events that invalidates him in his daily functioning is often one of the best ways to get a refugee some sort of social assistance, material resources, or an application for asylum in Europe or North America. As it has already been explored by Kleinman in other cultural settings for refugees, “in order to gain access to public assistance and resettlement, the refugee person must first become a passive and innocent “victim”, unable to represent himself”.[17] Subsequently, he or she is labeled a “patient” and thereby transformed from someone who has experienced trauma to someone who has a disorder.

Describing human suffering in the face of war and loss as “symptoms of a disorder”, and pathologizing human reactions to a collective political violation and social distress, can be stigmatizing for the refugee. It can ultimately reinforce in him/her the feeling of disempowerment, alienation and dehumanization. Many refugees I met between November 2013 and January 2014 in the clinics of the NGO where I work as a consultant psychiatrist have expressed such sentiments. Here are a few sample testimonies:

A man in his fifties: “I don’t understand why I have to take medication. Am I sick if I am grieving the loss of my son that I saw dying in the street under the bombings?”.

A woman in her forties: “I live under the stairs of a deserted building and I have lost everything I have. I feel I am not a human being anymore. How are you going to heal all that? Can’t you just help me find a shelter?”.

A young man in his twenties: “I couldn’t obtain an application for resettlement unless I had a report that I am severely mentally damaged by everything I witnessed in the war and I might have overemphasized it… But now even if I travel, who is going to accept employing a refugee with mental problems?”.

Like many other testimonials, these sentiments are embedded in complicated, personal stories. The victim status, at least for international donors, has become a clinical medical condition rather than a human condition invoked by a collective experience of suffering under war. Surely, victims of war need psychological support, and a lot of patients benefit from clinical treatment, especially those who had pre-existing psychiatric disorders. However, this focus on individual reaction to social distress as being a psychiatric diagnosis (depressive disorder, PTSD, and others) tends to lessen the importance of addressing the main causes of this distress: lack of basic social human needs, violations of human rights, lack of safety, and discrimination. After all, these mental health conditions are the expressions and consequences of a collective social suffering and this is what needs to be urgently addressed.

A recent consensus of experts from the World Health Organization has tried to shed light on the lack of evidence of the effectiveness of trauma-focused interventions (individual psychotherapy and medications) in emergency settings. The report advocated for a system-wide public health approach that considers pre-existing human and community resources as well as social interventions.[18] In other words, experts seem to finally agree that the best immediate therapy for war and trauma-related stress is through social, rather than clinical interventions.

Conclusion

The health conditions of displaced Syrians in Lebanon seem to be deteriorating and to pose risks to the health of the host community, while threatening to overwhelm the host country’s national health system. An emergency plan to support health and social services must be implemented by the Lebanese government, in cooperation with Lebanese civil society organizations and municipalities. As recommended by public health professionals assessing conditions in the field, this plan should fully integrate the work of the Ministry of Public Health and the Ministry of Social Affairs into a collaborative scheme.[19] Such an implementation requires financial support for Lebanon from all potential donor countries and the UN, as well as the provision of personnel and medical supplies. UN agencies need to place greater political pressure on donors to deliver the pledged funds, and on the Lebanese government to properly manage and disburse these funds for the benefit and treatment of Syrian refugees.

Concerning mental health interventions in this emergency setting, the current “disorder” paradigm underlying funded mental health services needs to be challenged by developing a more global and public health approach. This can be reached by the health working focus groups within UNHCR, in order to integrate practical interventions and services in the mental health policy for improving quality of life, protect human rights and basic human security: the lack of these are indeed the main causes of many of the psychological conditions among Syrian refugees.

References :

[1] UNHCR. “Syrian Regional Refugee Response”. (Accessed January 28, 2014).

[2] Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF): “Misery Beyond the War Zone: Life for Syrian Refugees and Displaced Populations in Lebanon”, 2013. (Accessed January 28, 2014).

[3] See note 2 above, idem.

[4] Coutts A, et al. “Assessing the Syrian health crisis: the case of Lebanon”, The Lancet (2013), published online on April 18, 2013.

[5] Refaat M, Mohanna K. “Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: Facts and Solutions”, The Lancet (2013), 382: 763-764.

[6] Ouyang H. “Syrian refugees and sexual violence”, The Lancet, Editorial (2013), 381:2056, published online on June 14, 2013.

[7] See note 2 above, idem.

[8] See notes 2 and 4 above, idem.

[9] See notes 4 and 5 above, idem.

[10] See note 4 above, idem.

[11] See note 4 and 5 above, idem.

[12] See note 6 above, idem.

[13] See note 2 and 4 above, idem.

[14] See notes 4 and 5 above, idem.

[15] PTSD is a psychiatric disorder that can occur after witnessing or going through a traumatic experience, that includes avoiding any reminder of the trauma, reliving the traumatic event through nightmares or flashbacks, and experiencing a chronic state of hypervigilance.

[16] Van Ommeren M, et al. “Mental and Social Health During and After Acute Emergencies: Emerging Consensus?”, Bulletin of the World Health Organization (2005), 83:71-76.

[17] Kleinman A. et al. “The Appeal of Experience; The Dismay of Images: Cultural Appropriations of Suffering in Our Times”, Daedalus (1996), 125(1): 1-23.

[18] See note 16 above, idem.

[19] See note 4 above, idem.

Mapped through:

Articles, Inequalities, Discrimination and Marginalisation, Lebanon

Related Articles