The Right to Innocence after Pardon: Egypt’s Court of Cassation Supports the Right to Appeal

On 25 November 2018, Egypt’s Court of Cassation issued a ruling holding that a partial presidential pardon from the remainder of a sentence does not preclude the continuation of appeal procedures before that court. This goes against previous rulings in which the court had consistently refused to examine appeals filed by defendants for whom pardons had been issued, deeming that the matter was out of the judiciary’s hands.

The successive Egyptian constitutions gave the president of the republic the power to pardon convicts completely or commute their sentences.[1] Presidents have consistently used pardons to release people sentenced in criminal cases. On multiple occasions, they have also used these decisions as a tool to pardon political opponents and defendants in accordance with the current political circumstances.[2] This has become more frequent since the current president took office in 2014 as he has issued approximately 20 presidential pardons encompassing thousands of detainees.[3] The cohort targeted by the pardons has also differed in accordance with their intended purpose and political aim. Sometimes they encompass people affiliated with the Islamist current, whereas other times they encompass youth affiliated with the civil current. The latter has reached the point where a permanent committee for presidential pardons was formed in the youth conferences that the President’s Office regularly holds, which shows that the current regime is relying on presidential pardons as a systematic policy for handling the Egyptian political situation.[4]

The legal effect of presidential pardons has been one of the important issues that the Court of Cassation has addressed since its establishment, particularly with regard to whether it may examine appeals once the defendants have been pardoned. Hence, it is important to shed light on the change to that principle that the court had entrenched over past years.

Looking Backward: The Court of Cassation Yields to the Executive Authority’s Suspension of the Right to Appeal

The Court of Cassation repeatedly adopted a principle in many rulings over the years until it became an established principle that is difficult to change. This principle is that “the issuance of a pardon takes the matter out of the judiciary’s hands such that the Court of Cassation cannot proceed with examining the case and must decide that the appeal may not be examined”.[5] The court’s decision affects partial pardons, which result only in the (full or partial) cancelation or commutation of the sentence,[6] and not comprehensive pardons that erase the conviction from the outset.[7]

The most notable consequence of this approach adopted by the court for many decades is that although the sentence is pardoned or reduced, the pardoned person still bears a criminal conviction and all its legal effects, which means that there is no possibility of establishing their innocence. Chief among these effects is that pardoned persons have a criminal record, which could prevent them from being appointed in any government job, becoming a member of a municipal or local council,[8] or registering with the professional syndicates, which require good conduct for membership.[9] According to the court’s precedents, “A pardon from a sentence, even if it encompasses the subsidiary punishments and their penal effects, cannot in any case affect the act itself and does not erase its criminality”.[10] This means that even if the pardon includes the supplemental punishments, such as parole and the seizure of funds, and the penal effects of the conviction, such as exclusion from public service, the person’s criminal record is not erased nor are they removed from the police departments’ mug books. Hence, the pardoned person’s only option for eliminating these legal effects of conviction is to pursue rehabilitation procedures, which can only begin six years after the date that the conviction is implemented and could cost much material and moral damage.[11]

Establishing Defendants’ Right to Appeal Despite Being Pardoned: A New Perspective on Presidential Pardons?

In November 2018, in an unprecedented ruling, the Court of Cassation ruled to continue examining an appeal filed by a person accused of possessing cannabis even though he had been released after being included in the pardon the president issued on 23 July,2018, the holiday commemorating the July Revolution.[12] As we explained, a pardon does not erase the conviction. Hence, the court deemed that “as the appealer aimed, via this appeal, to have the court… overturn the ruling and retry him… seeking to exonerate himself from his charge, his interest in this appeal still stood, especially as the aforementioned presidential pardon is a partial pardon from the remainder of the sentence and not a comprehensive pardon”.[13] In truth, this change in the court’s perspective on the nature of the effects of pardons and the need to provide pardoned persons with a chance to establish their innocence before their natural judge is extremely positive and praiseworthy.

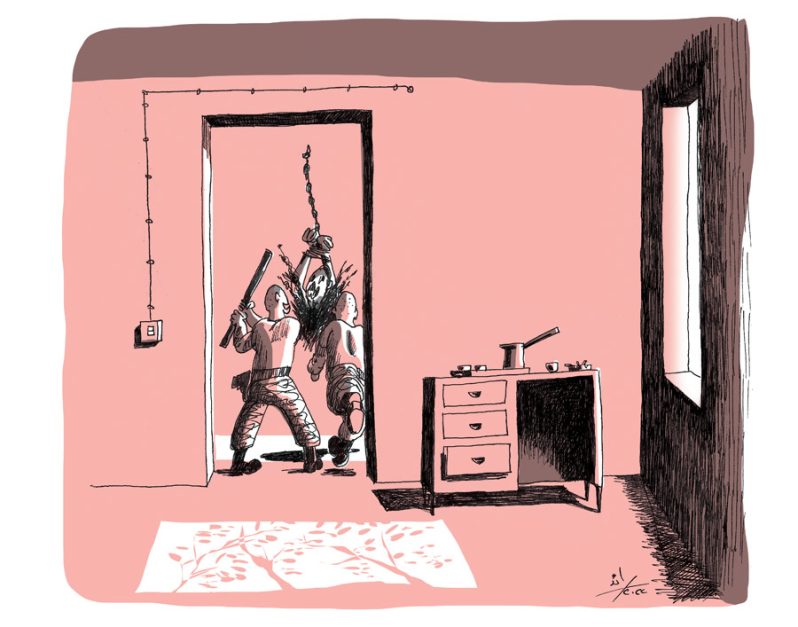

Primarily, presidential pardons are supposed to be the last means for a convict to appeal the case or seek exemption from punishment. Therefore, the pardon must be issued after the ruling imposing the sentence has become final and closed to any ordinary means of appeal. Hence, the head of the executive authority must use this extraordinary power (personal pardons) within the narrowest limits and in a manner that does not infringe upon the judicial institutions’ work or conflict with their independence. However, the contemporary reality in Egypt has taken the power to pardon in a different direction, that of pardoning sentences before all levels of litigation are exhausted. The Court of Cassation had to deal with this reality over several decades. For many years, it took the easy course – namely not to engage with cases where pardons had been issued – until it recently changed its stance and began taking the course desired from it,namely to ensure that justice is done even when the sentence has been pardoned. From another angle, this ruling’s timing is another point to the court’s credit. It shows that the court sees the entire landscape as recent years have witnessed an increase in random arrests followed by years of remand and then release under presidential pardons. Convicts who might have been arrested arbitrarily or at random at a protest or some other activity and then pardoned by a presidential decision should not pay the price for the rest of their lives with a criminal and social stigma that impedes them from continuing a normal life.

Conclusion

The president’s power to issue decisions pardoning or commuting sentences is enshrined in most of the world’s constitutions.[14] Hence, the real crisis concerning presidential pardons in Egypt lies not in the president’s power to pardon in and of itself but in the use of this power for purposes other than that for which it was legislated, as previously explained. Therefore, the move by the Court of Cassation to amend its principle is a testament to its clear view of Egypt’s judicial and political reality and its desire for a course correction to preserve the futures of thousands of youths facing the specter of arrest, years of detention, and then a presidential pardon followed by communal disgrace and a criminal record akin to a death certificate. Egypt’s head of government must heed this issue and stop using presidential pardons as a negotiating card to influence the political landscape and form understandings with adversaries and opponents.[15]

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Egypt, Presidential Pardon, Appeal, Court of Cassation

[1] Article 43 of the 1923 Constitution, the first permanent constitution in modern Egyptian history, stipulates that, “The King shall establish and confer civilian and military ranks, orders, and other honorary titles. He shall have the right of coinage pursuant to the law. He shall also have the right to pardon and commute sentences”. See also Article 155 of the current Constitution.

[2] The most notable is Decree-Law no. 241 of 1952, issued after the July Revolution and granting a comprehensive pardon for crimes committed for a political reason or purpose from 26 August 1936, to 23 July 1952.

[3] “Qararat al-‘Afu al-Ri’asiyy: al-Sisi Yamnahu al-Huriyya li-8661 Sajinan (Taqrir)”, Masrawy, 17 May 2019.

[4] “Lajna al-‘Afu al-Ri’asiyy.. al-Dawla Tu’idu al-Amal li-l-Shabab al-Mahbus wa-Tada’uhum ‘ala al-Tariq”, Mobtada, 12 August 2019.

[5] Court of Cassation rulings in Appeal no. 1 of judicial year 8, issued 29 November 1937; Appeal no. 2037 of judicial year 48, issued 9 April 1979; and Appeal no. 33026 of judicial year 2 (Consultation Chamber), issued 19 May 2013.

[6] Article 74 of the Penal Code stipulates that, “Pardoning a sentence requires canceling it in full or in part or substituting it with a lighter, legally prescribed punishment”.

[7] Article 76 of the Penal Code.

[8] The second paragraph of Article 75 of the Penal Code: “If a sentence is among those prescribed for felonies, pardoning or substituting it shall not encompass the deprivation from the rights and privileges stipulated in the first, second, fifth, and sixth paragraphs of Article 25 of this law”.

[9] Court of Cassation ruling on Appeal no. 3 of 1956, issued by the Criminal Department for Syndicates in the session of 4 February 1958.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Article 537 and Article 552 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which govern the conditions and procedures for rehabilitation and its legal effects.

[12] Court of Cassation ruling on Appeal no. 23745 of judicial year 87, issued on 25 November 2018.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Most of the world’s constitutions enshrine the power of the president of the republic to issue decisions pardoning or commuting sentences. This power granted to the head of the executive branch is one of the remnants of monarchy that have persisted in the eras of republics despite the adoption of the principle that sovereignty belongs to the people. It also appears clearly in the history of the Islamic state over the centuries as the wali al-amr [the ruler] was treated as the supreme judge who imposes and pardons sentences. See “The History of the Presidential Pardon”, Clemency Project, 30 December 2018.

[15] The constitutional legislators heeded the issue of excessive use of the pardon power and, because of the major impact pardons have, tried to constrict the president’s power to issue them in general in order to limit their misuse and ensure that the head of the executive branch does not handle such an absolute power alone. Hence, the legislators stipulated certain procedures, such as consulting the Council of Ministers regarding partial pardons and obtaining Parliament’s approval for comprehensive ones.