The Moroccan Judges Club: First Appraisals

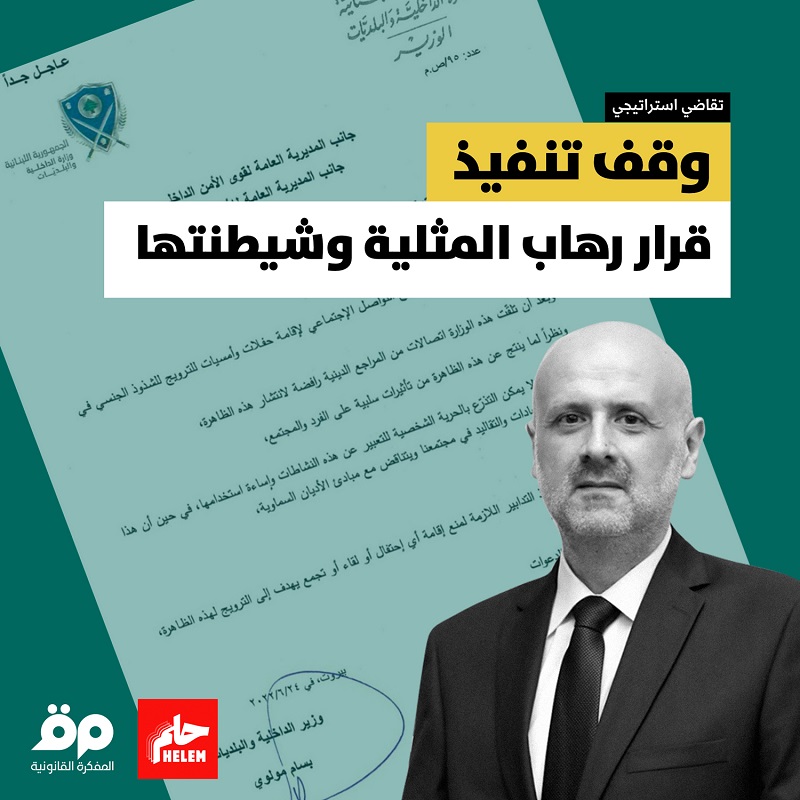

Editor’s Note: On the morning of March 15, 2011, five young judges launched a Facebook page entitled the “Moroccan Judges Club Page”[1]. Most of them had fictitious names. Before long, dozens of judges joined in while concealing their identities, given that the laws existing at the time did not guarantee their freedom of expression.

Within a short period of time, this Facebook page became a space for interaction among the judges on judicial affairs. In addition to the marked role of the Arab revolutions in launching this judicial movement, the re-opening of the Higher Judicial Institute after years of suspending admission into its ranks was another contributing factor. Many of the youth that graduated from the institute in the past few years were able and willing to use and handle modern communication technology.

The new Moroccan Constitution of 2011 had enshrined several judicial rights, including the judges' right to form professional associations and the right to free expression. On August 20, 2011, a few weeks after the ratification of the constitution, the Moroccan Judges Club turned into an actual club.

Before long, the Club emerged as an unequivocally independent youth group based on the principle of equality among judges. This was in contrast to the country’s single association of judges, al-Widadiya al-Hasaniya (Hassania Association of Magistrates, Amicale Hassania des Magistrats Marocains), which is characterized by hierarchy and its conformity to the dictates of the ruling authority. The Club’s actions affirmed its independence. The Legal Agenda has published several articles on the emergence of the Judges Club. This article highlights the Club’s major activities, which represents one of the most fruitful outcomes of the Arab revolutions.

Yes to Right of Assembly and Expression, No to an Absolute “Right of Reserve”

Since its launch on social media outlets, the Moroccan Judges’ Club (MJC) went into action gear to entrench the right of freedom of expression for judges, and to pull them out of the isolation produced by their abidance to the “right of reserve”.

The Club's innovative position in this regard was strengthened through the insistence of its founders to launch it out in public open space after a decision by the public authorities to close the school they had rented to hold their founding meeting. This was also enhanced by the Club's success in attracting hundreds of judges within a short period of time, as well as its success in establishing regional offices throughout Morocco.

This was also unequivocally entrenched by the deliberations of the first session of the MJC’s National Council that took place on November 26 and 27, 2011. Facts on the ground affirm that judges cannot live in isolation from their surroundings, particularly given the social transformations taking place at so many levels. Conditions on the ground also confirm the need to lay the foundation for a cooperative relationship with the media that would enable the discussion of judicial matters in public, without disrespecting the ethics of the profession.

The MJC reached out to professional associations that have the same goals and objectives, without compromising its independence or commitment to pluralism. The MJC refused to be considered as part of al-Widadiya al-Hasaniya. Indeed, the Club raised the notion of associational representation when it objected to its exclusion from the National Dialogue Commission in favor of the al-Widadiya al-Hasaniya.

Of significance was the Club's effort to resist several attempts by some government and judicial officials to restrict the freedom of judicial assembly. In addition to filing a lawsuit against the closure of the school that was rented to hold their founding meeting, the Club issued a number of statements condemning the harassment by judicial officials who sought to undermine the Club's decisions on various issues[2].

One of the most significant acts of resistance was the solidarity protest held by the Club outside the Court of Cassation, in which counselor Mohammed Anbar (the only Cassation Court judge who joined the Club when it was established) took part. Subsequently, Anbar was arbitrarily transferred from his position as the head of chamber at the Court of Cassation to the Public Prosecution judiciary. The move was interpreted as an implicit message to Cassation Court judges that they could meet the same fate if they joined the judicial movement[3].

No less important was the large number of judges, including the author of this article, who began to write explicit critical articles on judicial issues for daily Moroccan newspapers or online. The large number of articles by the Club's members created a new judicial reality. In this context, the Club's president, Yasin Mukhli, was summoned by the Inspector General Office for questioning about a statement he had made regarding the presence of irregular administrative detention centers. This summoning allowed him to clarify his position and understanding of the “right of reserve”[4].

The Development of Judicial Reforms: Material and Moral Interests

The judicial movement in Morocco which was inaugurated by the new constitutional amendment coincided with a critical moment in the history of the national judiciary, namely the declaration and enforcement of the new Constitution through regulatory laws and the start of a national dialogue.

The Club refused to participate in official national dialogue sessions on judiciary issues citing the Club’s exclusion from the oversight committee, and interpreting that exclusion as a deliberate move designed to ignore it as a representative of the judiciary. The Club’s lack of participation did not prevent it from busying itself with developing the required judicial reforms. Since the first session of its National Council which was held on November 26 and 27, 2011, the Club distinguished between urgent issues relating to judges and other reform issues.

The Club demanded an immediate adjustment of the salaries of judges to commensurate with the tasks assigned to them, in order to safeguard their independence and create a sense of equilibirium between the judicial authority and other branches of governance.

Furthermore, and after identifying the dysfunctionalities of judicial institutions, the Club called for supporting the institution of the Higher Judicial Council by empowering it to practice its authorities as stipulated by the Constitution. The Club put forward a number of proposals regarding the election of Council members in a transparent manner and without the stipulation of any seniority, in order to eliminate any hierarchy inside the judiciary. It also proposed that the inspection authority be independent, with its members being elected by the judiciary and for a limited term in office.

The Club also called for reviewing the controls and formats of appointments in a manner that would guarantee equal opportunity and would take the judge’s social status and living conditions into account. Another demand was the automatic promotion of judges regardless of fiscal constraints. The Club also called for adopting a transparent disciplinary code in a manner that would guarantee fair trials and pave the road towards requiring the consent of judges before their transfer.

Furthermore, on May 5, 2012, the MJC presented a document signed by more than 2,000 judges, calling for the independence of the Public Prosecution from the Ministry of Justice.

The Judges' Right to Protest: Methods and Mechanisms

In an unprecedented development in the history of the judiciary in Morocco, the Club has consistently called for the right to protest, particularly in the second session of its National Council which was dedicated to discussing the forms of protest. The discussion of this issue reached a climax when more than 2,000 judges marched in their gowns to the Court of Cassation on October 6, 2012. Furthermore, the Club threatened with a strike.

As a result of the national and international reaction to this stand, Morocco’s Al-Sabah newspaper dedicated its weekly issue[5] to address the following question: Does a judge have the right to protest? This question, which was presented to officials in professional associations, exposed the different approaches to achieve the same goal, and touched on the legality of protesting or staging strikes. The chairman of the Moroccan Judges’ Club was the only one to stress the legality of the protests and strikes organized by the Club. He said that the philosophy, for which the right of judges to form leagues and assemblies was stipulated, is based on guaranteeing the openness of judges to society and forgoing their right of reserve. He reminded people of the international experiences in this regard.

Monitoring Attempts of Intervention in Judges' Work

The Club has become a sort of observatory monitoring interference in legal matters. In this capacity, the Club issued central and regional statements to expose any attempt to undermine or affect the independence of judicial work. Cases of interference were thus documented and judges were encouraged to take the initiative and to report them. This was done in tandem with exhortations emanating from similar directives stated in the newly ratified Constitution, under which failure to report such abuses was subject to disciplinary measures.

The most important instance of interference recorded by the Moroccan Judges’ Club was probably the documentation of attempts by judicial officials to interfere in cases before the court, under the pretense of hierarchy. One of the most prominent documentations was the report submitted by the judges of the Court of First Instance in Sidi Qasem to the Moroccan Judges’ Club on May 8, 2013. The report referred to interference by the Inspector General Office.

The Club equally objected to:

The demand by the head of the Court of First Instance in Al-Hoceima for a judge to explain the factors behind the latter’s evaluation of money due in a particular case[6]; and

A letter from the head of the Court of First Instance in Zakurah to the head of the work accidents division, which included special instructions related to specific files[7].

Many cases of lobbying and assaults on judges were also monitored and objected to. Some of those cases of interference were committed by political lobbying groups. The most serious of these were the “shameful” statements made by the mayor of Fez a few days after one of his children was detained in a case of assault and battery.

During a party meeting, the mayor hurled shameful expletives against the deputy crown attorney in Fez. The prime minister later told the media that “public prosecutions are treating the mayor of Fez unjustly”. The judges denounced the growing and continuous assaults against them and the laxness of official parties in rushing to their aid. Their discontent culminated in the “protest of anger”[8]. This protest was organized at the Court of Appeals in Kenitra on May 16, 2013. Hundreds of judges arriving from all parts of Morocco participated in the event.

Solidarity Visits with Judges Who Were Assaulted

On a related note, the Club contributed to restoring the spirit of cooperation among judges, and the revival of solidarity among them in the face of dangers threatening their independence and freedoms. On more than one occasion, Club member judges made visits of solidarity to their colleagues who were assaulted or harassed. These visits included solidarity campaigns with the deputy crown attorney in Fez, the judge of Beni Mellal, the judge of Kenitra, and the solidarity visit to the judges of Tawnat and to Judge Mohammed Anbar. These solidarity visits had a large impact on consolidating the ranks of judges and unifying them in the face of the tyranny of other branches of government, and the connivance of some state apparatuses.

Openness to Major Societal Issues

Until 2011, the Moroccan judiciary in general remained at a distance from major social issues and for a variety of reasons. Top among them was the exaggerated overlap between expressing legal opinions and participating in politics, as well as the excessive abidance by the right of reserve.

The contribution of al-Widadiya al-Hasaniya to national dialogue was thus very limited or almost non-existent. With the establishment of the Club, the separation wall between judges and their societal environment started to gradually crumble. One example was the Club's statement regarding the judges' oversight of the legislative elections on November 25, 2011, in which the Club called for the setting of mechanisms that can ensure full judicial supervision of the entire election processes[9].

The interest of the Moroccan Judges’ Club in national affairs was also evident in its statement on July 3, 2013. The statement called for humanizing arrest practices and administrative detention conditions, as well as improving the space reserved for illegally detaining foreigners. In partnership with other organizations, the Club held a number of seminars to discuss these issues[10].

One such seminar alluded to the need for creating effective alternatives to freedom-depriving penalties and for the revision of the criminal justice system[11]. In the same respect, the Club’s president spoke to two national newspapers about the presence of administrative prisons in southern Morocco and called for their closure. His statement stirred so much controversy, and as a result he was summoned to the Inspector General Office.

In its statement issued on July 3, 2013, the Club's Executive Bureau called for the abolishment of prison penalties in crimes relating to violating the law of the press. This was an unprecedented initiative from within the judicial body, given the taut relationship between the judiciary and the media. Until recently, the judiciary’s impact on the freedom of the press was seen in a negative light, given the legal hounding of a number of Moroccan journalists.

The Club also issued a statement calling for the revision of provisions relating to underage marriages[12].

Efforts to Synthesize the Justice System

Over the past decade, unofficial national and international reports were published painting a “bleak” image of the Moroccan judiciary, and indicating a clear proliferation of the phenomenon of bribery inside the justice system as a whole.

In response to these reports, the Club decided on an unprecedented initiative: the launching of a national program to “moralize” the justice system under the remarkable slogan: “Courts without Bribes”.

The walls of Moroccan courts were thus covered with posters carrying the slogan “No to Bribes” in several languages. Subsequently, an undeclared clash erupted between Club activist judges working on promoting these posters throughout court buildings, and others who removed the posters. The Club also concluded a partnership agreement with the Moroccan Society for Combating Bribery (Transparency)[13].

News reports cited the involvement of some judicial officials in fighting this campaign seen by them as an assault on the judiciary. The latter had -until recently- refused to admit the presence of corruption within its circles.

In this context, the national protest outside the Court of Appeals whereby hundreds of judges of different ages and ranks and from all over Morocco stood wearing their official gowns and carrying a number of placards summarizing their demands, amounted to an uprising within the judiciary. The most significant of these placards was “No to Bribes”, written in several languages.

The Ministry of Justice immediately issued a statement insinuating that “not everyone who participated in the vigil is associated with reform and integrity, and not everyone who was absent from it is associated with delinquency and corruption”[14].

The Moroccan Judges’ Club continued its gestures with all the members of the Club's Executive Bureau announcing that they will declare their assets and debts publicly. The initiative was later endorsed by the rest of the Club's members.

The ongoing project of “moralizing” the justice system continued with an accelerated pace through the role of the Ministry of Justice's inspector general office. The latter carried out a number of investigations based on citizen complaints [of instance of corruption]. More than one judge was set up. But the ministry’s actions did not totally steer away from media sensationalization and fell short of upholding the presumption of innocence and the legal guarantees which govern the pursuit and investigation procedures. The Moroccan Judges’ Club issued a statement in this respect, calling for the combating of delinquency in the judiciary away from any political or media involvement. It also declared its disavowal of any judge proven to have committed disgraceful acts[15].

Conclusion

Basic impressions may be gleaned from reviewing two years in the life of the Moroccan judicial movement. One is the return of the spirit of collaboration among judges and the revitalization of notions of solidarity among them, in the face of dangers confronting their independence and freedoms. Another transformation is the growing sensitivity of judges towards any attempt to influence their independence, as well as an increasing readiness on the part of judges to report such interference.

In addition, the Club's activity and actions triggered a positive response to their demands regarding a number of “hot” issues. Judges themselves, however, remain the main group to be relied on to preserve the gains achieved recently. They are the ones responsible for protecting this judicial action aimed at building the fundamentals of an independent judicial authority.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

References:

[1] Judge Mohammed Anbar, in an interview with The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 4.

[2] Examples include the two statements by the Club's Executive Bureau, dated January 14, 2012 and January 9, 2012.

[3] Murad Al-Amrati: The issue of Judge Mohammed Anbar, president of a chamber at the Court of Appeals, published in Al-Akhbar newspaper, Issue No. 143, dated May 3, 2013; interview with Mohammed Anbar with The Legal Agenda journal, Issue No. 5, dated July 2012; and interview with Mohammed Anbar by the website Hiba Press, dated July 2, 2012.

[4] Anass Saadoun: A Reading in the Summoning of the Chairman of the Moroccan Judges Club to the Inspector General Office, published in Hespress website on October 2, 2012.

[5] Special file of Al-Sabah Newspaper for Saturday and Sunday, October 13 and 14, 2012.

[6] Statement by the Executive Bureau of the Club, dated April 27, 2013.

[7] Statement by the Executive Bureau of the Club, dated February 16, 2013.

[8] Anass Saadoun: A Reading in the Reasons behind the Protest of Anger, The Legal Agenda, dated May 14, 2013.

[9] Anass Saadoun: For a Total Supervision of Judges over the Elections, published in Al-Akhbar Newspaper on January 18, 2013.

[10] Seminars on December 8, 2012 and December 29, 2012.

[11] Adel Fathi: The Judiciary and its Black Box: The Reality of Prisons or the Reality of the Judiciary? Al-Masa Newspaper, published on September 8 and 9, 2012.

[12] Statement by the Executive Bureau of the Moroccan Judges' Club, dated December 3, 2012.

[13] For example, the “Training Course on Mechanisms to Combat Bribery”, September 3, 2012, and December 1, 2012.

[14] Statement by the Ministry of Justice and Freedoms, issued on October 7, 2012.

[15] Statement by the National Council of the Moroccan Judges' Club, dated March 23, 2013.