The Libyan Migrant Route: Torture on Land and Terror at Sea

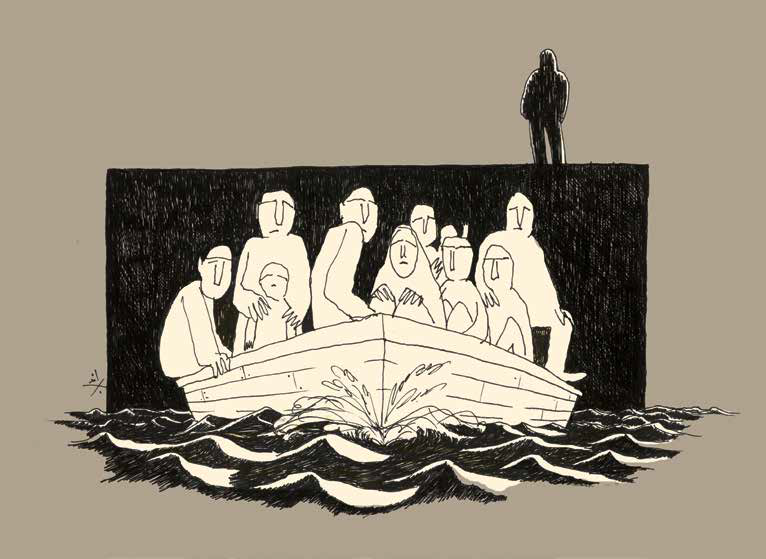

Libya has a coastline that runs approximately 2,000kms along the Mediterranean Sea, the country lies close to southern Europe, and it shares 4,000kms with six countries. Consequently, Libya is an ideal crossing point for many migrants (Africans, Syrians, and occasionally Libyans) dreaming of a decent life in Europe. While illegal migration has become a great concern for the international community and Europe, the migrants themselves remain at risk of becoming its victims at most stages of their journey.

Illegal Migration: Between Two Systems

This issue is not tied to the state of instability in Libya. Even under the previous regime, migrant-smuggling syndicates operated on Libya’s western coast, and the coast guard and local police could not put a stop to them. For example, in 2008, 200 migrants died when a boat sunk. In 2009, rights organizations estimated the annual number of migrants bound for Italy to be 100,000. During the armed conflict in the revolution of February 17, 2011, late Libyan President Muammar Gaddafi exploited the migration issue to threaten Europe with the danger that would come, should his regime fall. For example, in his interview with a French newspaper, he stated that, “hundreds of people will invade Europe from Libya, and there won’t be anyone to stop them”.[1]

After Gaddafi fell, the situation deteriorated further. Three transitional governments took turns in power, the state institutions weakened, and the country plunged into political and military crises marked by a multiplicity of governments, and the proliferation of armed groups. Subsequently, the number of clandestine migrants in Libya bound for the shores of Southern Europe alarmingly increased. They found themselves between the hammer of death boats, and the anvil of death merchants and merciless detention centers.

Horrendous Violations

The migrants who cannot cross the Mediterranean Sea and are detected are lodged in detention centers that do not fulfill the lowest sanitary and subsistence requirements. Most of these centers are spread across the western part of the country. In them, the migrants –including women and children– suffer torture, rape, forced labor, and extra-judicial killings; not to mention the danger of forced return in contravention of international treaties. This was mentioned by Special Representative Martin Kobler, Head of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya.[2]

In a report issued in July 2016, Amnesty International stated that it spoke to 15 women, most of whom had lived in perpetual fear of sexual violence throughout the journey to the Libyan coast. According to their testimonies, women are sexually assaulted by the smugglers themselves, the human traffickers, and members of militias. Many of them mentioned the prevalence of rape, which had prompted them to take contraceptive pills lest they become pregnant.[3]

Another report, published by the German newspaper Welt am Sonntag, stated that according to a report that the Embassy of Germany in Niger prepared for the German government, migrants face execution, torture, and other systematic violations of human rights in camps in Libya. The paper related that, “executions of countless numbers of migrants and torture, rape, bribery, and banishment to the desert occur daily”. The paper also conveyed testimonies stating that in one prison, five executions occurred weekly, with advanced warning and always on a Friday, to make way for new arrivals. In other words, the smugglers seek to increase their revenue by killing a number of migrants.[4]

In one of the gravest developments regarding this issue, the International Organization for Migration recently stated that the phenomenon of trafficking is increasing among African migrants who pass through Libya, and so-called slave markets have emerged. Migrants are detained and then ransomed, and forced to work without pay or sexually exploited. They are sold in markets as a commodity for prices ranging from US$200 to US$500.[5]

In the same context, a UNICEF report stated that 26,000 children, most unaccompanied, crossed the Mediterranean Sea last year. The report warned that many children face violence and sexual abuse from smugglers but remain quiet about their experiences lest they be detained or deported. Hence, the plight of children has become part of the general plight of collective migration to Europe during the last two years.[6]

Migration Routes Through the Libyan Desert

While there is much focus on the risks of migrating at sea, the risks on land –especially in Libya– are rarely discussed. In southernmost Libya, far from the eyes of the media and rights organization, illegal migration and smuggling syndicates take advantage of the length of the southern border and virtual absence of the state from the crossings. One of the most famous of these crossings is the Awaynat crossing located on the Sudanese border, near the city of Kufra in the southwest. Approximately 1,000 migrants enter via the crossing each day.[7] Smuggling syndicates receive them and, for a fee as high as US$3,000 per person, transport them in overloaded four-wheel drives across a long (approximately 1,200kms) and exhausting desert route. These vehicles follow bumpy tracks from Kufra to Ajdabiya along the Great Man-Made River. From there, they travel to Marada and then Bani Walid, ultimately arriving in the coastal city of Sabratha which lies approximately 150kms from the capital. Sabratha and Zuwarah are considered among the cities most active in the process of smuggling migrants to Italy via the Mediterranean shores.[8]

There are other crossing points in the south. Among them is the Jabal Malik crossing, which connects Egypt, Libya, and Sudan and receives 600 migrants and refugees each day according to the statistics of the Kufra branch of the Department for Combating Illegal Immigration; as well as the two al-Sarra Aouzou crossings on the Chad border, and a fourth crossing in the southwest on the Niger border.[9]

Accommodation Centers in Libya

Accommodation centers are spread across western Libya. They are administered by unspecialized and poorly qualified security bodies that do not distinguish between migrants and refugees. Since 2011, the illegal migration issue has formally been part of the Ministry of Interior’s portfolio. The reality is that the armed formations are the ones handling the migrants in the absence of any law regulating the status of migrants, until the Council of Ministers issued Decision No. 386 of 2014 on the establishment of the Department for Combating Illegal Immigration.[10]

There are 42 accommodation centers; 17 of them are in the western region and these are the ones that are actually active. They are located in Zliten, Khoms, Tripoli, Sorman, Sabratha, Zawiya, Gharyan, Janzur, Misurata, and Bani Walid. There is one accommodation center in the country’s east and there are disagreements over its affiliation. The bulk of the migrants are from Gambia, Niger, Ivory Coast, Senegal, Chad, and Sudan.[11]

Strangely, the migration and smuggling syndicates have began working virtually in the open. They prepare the accommodation centers and exploit the summer resorts, as well as old storehouses and factories to amass the migrants. They have even rented small farmhouses for lodging migrants. From the beginning of 2015 and throughout 2016, the issue developed at a rapid and dangerous pace, especially in Sabratha. The smugglers’ control over that city, as well as its harbors and even its land crossings, has become plainly evident.

The wooden boats are built and maintained on the roadside in front of passers-by and on farms. Their owners do not hide that they are preparing them to transport migrants across the sea.[12]

There is also one accommodation center in Kufra, Southeast Libya, that only has the capacity for 100 migrants and refugees but is sometimes overcrowded with 400. The center is gender-segregated, so families are separated. They also suffer poor living conditions, a lack of nutrition and medical treatment, and the status of women is particularly bad.[13]

UNICEF describes the accommodation centers in Libya as unsanitary and suffering from a scarcity of food and drinking water.[14]

According to a recent report on the period from December 2016 to March 2017 by the International Organization for Migration, the regions that host the largest number of migrants are Misurata (66,660), Tripoli (53,755), and Sabha (44,750).[15]

The Legal Framework

The Libyan legislative framework is incapable of providing any protection for the migrants. The existing texts only criminalize and punish the act of infiltration, i.e., irregular entry and residence (Law no. 19 of 2010), and stipulate that they must be returned to their countries. The texts do not take into account whether there is a real danger to the migrants’ lives. This is because Libya does not recognize the right of asylum as the country has not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention. Likewise, the Interim Constitutional Declaration makes only a modest mention of this right. The aforementioned law also punishes migrant-smuggling syndicates and those who exploit migrants.

Some experts believe that illegal entry does not provoke a violent backlash and instead evokes pity and sympathy from the members of Libyan society, who still see illegal migrants as victims of circumstances. Consequently, they argue that criminalizing this behavior is inappropriate and unnecessary.[16]

The Memorandum of Understanding Between Libya and Italy

The European anti-smuggling naval operation that begun in 2015 – Operation Sophia – failed to rescue [all] migrants crossing the Mediterranean Sea in primitive, overloaded boats. Similarly, the European Union’s attempt to train the Libyan coast guard did not curb the number of migrants.

Mohamed Taha Siala, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Libya in the Government of National Accord, went as far as to state that Operation Sophia encourages migration because migrants have come to count on being rescued in the sea before arriving at the Italian Islands of Lampedusa and Pantelleria. He thinks it is important to reconsider the operation, and to strive for economic development in the source countries.[17]

Perhaps this failure to curb the phenomenon pushed Italy at the beginning of this year, the most heavily affected [destination country], to pressure the Presidential Council of the Government of National Accord to sign a memorandum of understanding akin to a protocol complementing Libya’s previous agreements with Italy (most importantly the 2008 Treaty of Friendship, Partnership, and Cooperation). The memorandum began with 12 preliminary points that emphasize the historical heritage that the two countries share, strengthening values of cooperation and partnership, confronting the current challenges, the importance of border control, preserving the Libyan social fabric, and the previous agreements between the two countries. This was followed by eight articles containing the details of the memorandum. Article 1 Paragraph 2 stipulated that, “The Italian side shall provide support and funding in the regions affected by the illegal migration phenomenon in various sectors such as renewable energy, infrastructure, health, transportation, human resource development, education, staff training and scientific research”.

Paragraph C of the same article stipulated that, “The Italian side shall commit to providing technical and technological support to the Libyan bodies charged with combating illegal migration, and securing the land and maritime borders”. Article 2 detailed the obligations of each party’s obligations in six paragraphs, the second of which define Italy’s obligations in “equipping and funding the Libyan accommodation centers in accordance with the relevant standards”. Paragraph 3 emphasized “training Libyan personnel in accommodation centers to handle the migrants’ conditions”, while Paragraph 6 stated that the two sides shall “launch development programs, through appropriate job creation initiatives, for Libyans in the regions affected by the illegal migration phenomenon”. Article 4 stipulated that, “the Italian side shall fund the initiatives mentioned in this memorandum”.

The memorandum attempted to address the issue of returnee migrants by charging Italy with the responsibility for equipping and funding the accommodation centers. It no doubt aims to improve the living conditions in the accommodation centers that already exist –which is a positive point to its credit– but not necessarily to increase or expand them to the point of settling [the migrants in Libya].[18]

From another angle, many Libyan rights organizations think it is impossible to compare the European Union’s agreement with Turkey to this memorandum. [In their view], the memorandum aims to turn Libya from a “transit” country into a destination country by transforming it into a large migrant camp, without any regard for the migrants’ interests or protection in the context of political division, armed conflicts, and weak state institutions. Amassing the migrants in accommodation centers in Libya deprives them of their most basic rights, exposes them to grave risks and violations, and prevents them from even accessing services because of the inexperience of the bodies charged with overseeing these centers and the country’s poor conditions.[19]

According to rights lawyer Salah Marghani, female migrants face great dangers. In a comment on a tweet by Special Representative, Head of United Nations Support Mission in Libya Martin Kobler, Marghani wrote, “Thanks for your timid tweet in support of protecting migrant women from violence. You can protect them more by intervening to stop Italy from exploiting Libya’s present weakness and throwing the migrants into detention centers, and [to stop] the forced signing of memoranda of understanding on building a sea barrier around Libya’s shores to protect Italy and Europe from poor asylum seekers and leave them to face the hell of the ocean or land, with no regard for international humanitarian law”.[20]

Lawyer Azza al-Maqhur wondered why Italy has not fulfilled the earlier pledges that it made in the 2008 Friendship, Partnership, and Cooperation Agreement with Libya. She felt that there is no need for the memorandum of understanding as Italy already has several unfulfilled obligations under the previous agreement.[21]

Local organizations are not the only critics. Rather, even international organizations always condemn the deportation and detention of migrants. Amnesty International commented that the worst-case scenario is deportation, because in such cases it takes precedence over all considerations and principles, including these people’s human rights. It called upon the European Commission to reconsider its proposals regarding the deportation of migrants.[22]

According to the Washington Post, some aid organizations have also warned that the memorandum could cause enormous human losses by blockading thousands of migrants in Libya, where the rule of law has disappeared.[23]

In an interesting development, al-Maqhur, Marghani, and others filed a case against the Presidential Council and Government of National Accord before the Administrative Justice Department in the Tripoli Court of Appeal. In this case, they sought an immediate stay of execution on the memorandum and, ultimately, its annulment. The case cited several important points, including that the Presidential Council had no standing to sign the memorandum and represent Libya as it had usurped power.

The situation heated up on March 22, 2017, when the Tripoli Court of Appeal ruled in case no. 30 of 2017 to accept the contestation in form and merit, by temporarily staying the execution of the contested decision that put the memorandum into effect. While the ruling did not address the merit of the case and stayed the memorandum as a summary measure, it muddled the parties to the memorandum and reopened the debate about it. The Guardian opined that even though the court ruling against the agreement has been appealed, it has left a key aspect of the European Union’s refugee policy in limbo.[24]

Conclusion

Certainly, the migration problem is an international one. The international community must bear its consequences and search for remedies and solutions; to load them onto one country and not another is a major shortcoming that will lead nowhere. For this problem has three sides –the transit countries, the source countries, and the destination countries– and reducing it to the interaction between the transit and destination countries creates an imbalance and puts the burden on the transit country which is usually unable to handle the crisis. This is the essence of the migration problem in Libya, and it is important to compel the destination countries to bear the costs of real development projects in the source countries.

The political division and armed struggles exacerbate the problem. But that is another issue that will have repercussions on the future on all of Libya.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] Maghress, published on March 6, 2011.

[2] Website of the United Nations High Commissioner.

[3] Amnesty International report, dated June 2016.

[4] The Arab Weekly.

[5] Statement by Uthman al-Biblisi, representative of the International Organization for Migration in Libya, the Reuters Arabic website, April 29.

[6] BBC Arabic.

[7] Libya Center for Studying Crises statement by an official in the Department for Combating Illegal Immigration.

[8] Reports by the Libyan Center for Human Rights Studies.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Report by BEELADY for Human Rights, a Libyan rights organization concerned with migrant affairs.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Statements of the Libya Center for Studying Crises.

[14] BBC Arabic.

[15] Bawwabat al-Wasat website, April 28.

[16] See: Karima Amshere’s, “Qira’a fi Ba’d Nusus Qanun Mukafahat al-Hijra Raqm 19 li-Sanat 2010”, Majallat al-‘Ulum al-Qanuniyya, University of Azzaytuna, Tarhuna, Issue No. 6, Year 3, 2015, page 248.

[17] Libya Al Mostakbal website.

[18] Karima Amshere’s working paper on the memorandum of understanding signed between Libya and Italy. The paper was presented in the workshop held in the Tripoli municipal council on April 18, 2017, under the auspices of Bedaya For Human Rights Awareness.

[19] A joint press statement by 12 Libyan rights organizations on informal migration, published on the Libya Al Mostakbal website.

[20] A post on the personal Facebook page on April 7, 2017.

[21] Post on the personal Facebook page on April 3, 2017.

[22] Libya Al Mostakbal website.

[23] Al-Marsad al-Ikhbari website, April 27, 2017.

[24] Al-Marsad al-Ikhbari.

Mapped through:

Articles, Asylum, Migration and Human Trafficking, Libya

Related Articles