The Bill to Introduce an Electoral Threshold: Appraisal

Editor’s note: The Legal Agenda is collaborating with the Tunisian organization Al Bawsala to follow legislative activity in Tunisia. Hence, we are pleased to periodically publish, on our website and in our magazine, articles by analysts and writers from Al Bawsala, which has performed a distinguished role in tracking parliamentary activity, stimulating social participation in such activity, and tracking the decentralization process and public finance and bringing the latter closer to the citizens, thereby strengthening the foundations of democracy in Tunisia’s Second Republic. We hope that the collaboration between our two organizations will advance parliamentary work and the procedures for monitoring it in the Arab region.

The Internal Statute, Immunity, Parliamentary Laws, and Electoral Laws Committee (hereinafter “the Internal Statute Committee”) in Tunisia’s Parliament has approved the bill to revise the electoral law by introducing a 5% threshold into legislative elections.[1] This proposal has stirred political controversy concerning both its timing – the coming legislative elections are less than nine months away – and its content and potential effects on the representation of smaller parties and the diversity of the parliamentary landscape.

However, the diagnosis underpinning this proposal did not witness the necessary debate. There was much discussion about the crisis of governance, the difficulty of securing a majority, and the disruption of parliamentary activity as though these factors are fundamentally the result of the current voting system and therefore can only be solved by amending it.

Why Proportionality with the Largest Remainder Method?

The diversity of voting systems across different countries and experiences may be enough to prove that there is no ideal system. The choice of voting system is subject to a trade-off between the desired goals – such as justice, representation, and stability – that takes into account the specific circumstances of each context.

In Tunisia, the choice of a proportional voting system with the largest remainder method traces back to the constituent elections of 2011. The Higher Authority for Realization of the Objectives of the Revolution, Political Reform, and Democratic Transition selected this system to ensure the broadest representation possible in the elections for a constituent assembly charged with formulating a constitution.[2] It was then agreed that the system should be retained for the legislative elections. However, in an attempt to rationalize candidacies and public funding, a threshold of 3% of votes was adopted for public campaign funding in the form of post-election reimbursements, but did not, [i.e. the threshold] apply to the distribution of seats.

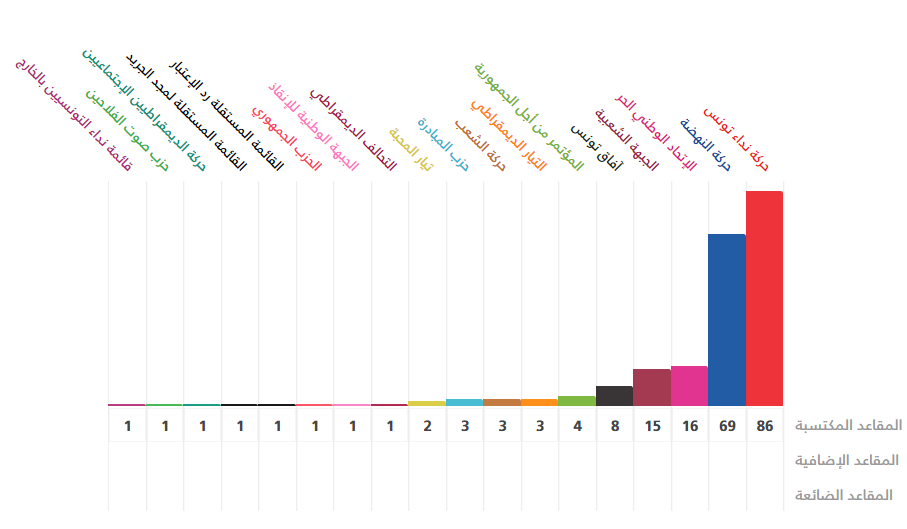

The current proposition before Parliament’s general session is a 5% electoral threshold for legislative elections, beginning with the 2019 elections. The proposed threshold not only excludes the lists in each district that obtains less than 5% of the votes from the distribution of seats; it also excludes the votes obtained by these lists from the calculation of the electoral quotient,[3] which compounds the benefit that the major lists and parties derive, as shown by the simulation that Al Bawsala conducted based on the results of the 2014 elections.[4]

The main argument underpinning the proposal may be the fragmentation of the parliamentary landscape, which makes it difficult to realize a majority capable of governing. The current voting system, which gives priority to achieving the broadest representation, may have been sound “in the beginning of the democratic transition”, but it “is becoming a negative factor” that must be “rationalized”, according to the explanation of reasons that accompanies the bill. The electoral threshold is thus presented as a precondition for “effective electoral results”[5] and, implicitly, as a solution to the governance crisis.

This diagnosis warrants much critique, for the 2014 results indicate that the current electoral system, even with the priority it grants to smaller lists, is not a cause of the fragmented parliamentary landscape.

A Parliamentary Landscape Fragmented Due to the Disintegration of the Largest Bloc

The current parliamentary landscape may seem fragmented to some observers as the largest bloc holds less than a third of the seats. However, this fragmentation is not a result of the voting system as the parliamentary composition produced by the 2014 elections consisted of two large blocs together holding more than 70% of the seats, and the Nidaa Tounes bloc alone held over 35%. In comparison with other parliamentary democracies, such as Germany,[6] Italy,[7] and Portugal,[8] where the largest blocs hold between 28% and 38% of the seats, it is difficult to consider this composition fragmented.

Hence, the fragmentation and instability of the current parliamentary landscape are a direct result of the disintegration of a number of the parliamentary blocs that the elections produced, particularly the Nidaa Tounes bloc, as shown by the “Mercato of Parliamentary Blocs” published by Al Bawsala.[9] The defections in the ranks of the Nidaa Tounes bloc began in 2016 with the formation of the Al Hurra bloc of the Tunisia Project Movement. Then the National Bloc appeared, which constituted a nucleus for the National Coalition bloc. Because of these defections, the Nidaa Tounes bloc lost more than half its MPs. It is difficult to attribute this loss to the voting system as its causes are political and structural problems within the party itself. The voting system should not be held responsible for the effects of party crises, and bolstering the major parties’ chances with an electoral threshold cannot be a solution because as long as these parties are susceptible to disintegration, increasing their representation is — to the contrary — a destabilizing factor.

Factors Disrupting Parliamentary Activity

There is no doubt that throughout the parliamentary cycles, Parliament’s activity has suffered from sluggishness and much disruption, both on the legislative and electoral levels. However, it is wrong to link this disruption to the voting system and the priority it grants to smaller lists. In the first parliamentary cycle, the opposition represented less than 15% of MPs, so the representation of smaller blocs cannot be considered a cause of instability and fragmentation of the [parliamentary] landscape. Rather, the opposition blocs have often voted in favor of the bills for organic laws, such as the Code of Local Collectives, the Law on Declaring Assets and Interests and Combatting Conflicts of Interest and Illicit Enrichment, and other bills that passed through the Consensus Committee.

As for the difficulties Parliament experiences in voting on some laws, they stem primarily from the phenomenon of absenteeism among MPs. During the parliamentary period, only two bills failed at the vote: the first approving a loan agreement and the second concerning a series of measures to reform the National Pension and Social Security Fund. In both cases, the issue concerned a regular law requiring 73 votes to pass. In other words, the parliamentary majority, theoretically consisting of approximately 130 MPs, failed to provide 73 votes even though it supported the bill. Of course, the reason was the growth of the absenteeism phenomenon.[10] We also should not forget the postponement and adjournment of general sessions and the rescheduling of other activities because the quorum required to approve the scheduled bill was not present.

Parliament’s bureau has been unable to take sufficient measures to end the absenteeism phenomenon. Even the salary deductions that the bureau imposed on some MPs remain restricted by the conditions put in place by the internal statute (three complete work days in general sessions concerning voting or six consecutive absences from committee activities, within the same month) and only affected an average of four MPs per month. Hence, the solution to the disruption of legislative activity is to revise the internal statute to impose more discipline on MPs such that they attend Parliament or to strengthen party work to impose certain conduct upon them.

Similarly, the disruption of Parliament’s electoral role, its failure to elect a constitutional court for more than three years after the constitutional deadline and to establish many of the constitutional bodies, and the fact that on each occasion it has wasted many months filling vacancies in the Independent High Authority for Elections, does not stem from the difficulty of providing a two-thirds majority in such a composition. To the contrary, the majority blocs (except for the current majority) have by themselves theoretically held a two-thirds majority. In practice, the disruption emerges, in particular, from a lack of agreement between the Ennahda bloc and the Nidaa Tounes bloc on the candidates, as in the case of the Independent High Authority for Elections and the Constitutional Court. Hence, the disruption of Parliament’s electoral role stems from the lack of a political will to elect the bodies, as was clearly evident when the confidentiality of the vote was exploited to flout the consensus announced regarding four candidates for the Constitutional Court. Once again, it is clear that the issue is not the voting system but political factors.

Will the Threshold Enable a Homogeneous Majority?

Many advocates of the electoral threshold attribute the crisis of governance to the voting system, which requires the major parties to form alliances to constitute a majority. Although proportionality with the largest remainder method makes it extremely difficult for a party to achieve an absolute majority of seats on its own, the threshold, contrary to what is being promoted, is in no way a solution to this “problem”. Al Bawsala’s simulation of the results of the 2014 elections assuming an electoral threshold shows that a 5% threshold would not have enabled the Nidaa Tounes party, even though it obtained 38% of the votes, to form an absolute majority on its own.[11] Instead of helping the first party to form a majority, the threshold makes it much less likely that there will be “natural” allies for it as representation will be restricted to the two major parties. As such, a high electoral threshold renders forced alliances practically inevitable, contrary to its stated goal.

Hence, the diagnosis underpinning the proposed amendment to the voting system, as well as the arguments put forward to defend it, is unsound. The current electoral system did not lead to the fragmentation of the parliamentary landscape, nor is it responsible for the governance crisis or the disruption of parliamentary activity.

The Timing of the Change to the Voting System

Although proportionality with the largest remainder method, like other voting systems, is open to critique and review, changing the voting system months before the elections poses a large issue.

The electoral law prohibits changing the division of electoral districts less than one year from elections.[12] This provision is explained by the need to prevent a ruling majority from using such changes to influence the results of the coming elections. The same philosophy applies to changing the voting system by introducing a 5% electoral threshold as its direct effects on the results and indirect effects via its influence on voters’ choices could steer the election results in favor of the major parties. Rather than postponing the examination of the electoral law amendment because of the tight timeframes, the Internal Statute Committee used the pretext of tight timeframes and urgency to pass the bill without debating it. This occurred immediately after the hearings were finished and one day after the deadline to submit written opinions, so the MPs had no chance to view and debate them.

Given the crisis of confidence in the political class, the fragility of the democratic process, and the crises that have afflicted the Independent High Authority for Elections, any change to the voting system in favor of the major parties just months before the electoral process will lead to doubt in that process, doubt that we do not need.

The electoral law, particularly the voting system, is an extremely sensitive subject that the legislature must handle carefully and deliberately rather than by rushing and forcing changes through. Certainly, the electoral law contains many negatives and defects related not necessarily to the voting system but to electoral funding, electoral sanctions, conducting the campaign, and other issues, and they all require serious study and an accurate diagnosis of the problem before we search for a solution. We should not forget that the issue does not necessarily stem from the legal text, and nor does the solution.

This article was published in collaboration with the Tunisian association Al Bawsala. It is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Electoral Law, Electoral Threshold, Legislative Elections, Tunisia

[1] An electoral threshold is a technique sometimes used in electoral laws, especially those that employ proportionality. It consists in a minimum percentage of votes that each list must obtain in order to enter the distribution of seats.

[2] Michael Lieckefett, “La Haute instance et les élections en Tunisie: du consensus au pacte politique?, Confluences Méditerranée”, No. 82, Été 2012, p. 136.

[3] The electoral quotient is determined by dividing the number of votes cast by the number of seats allocated to the district. A list receives the number of seats proportional to the number of times it obtains the electoral quotient, and the remaining seats are distributed according to the largest remainders.

[4] https://majles.marsad.tn/2014/simulation/scrutin

[5] Explanation of reasons included in Bill no. 63 of 2018 on Revising and Complementing Organic Law no. 16 of 2014, Dated 26 May 2014, on Elections and Referendums.

[6] The largest bloc in Germany’s Parliament is the Christian Democratic Union of Germany with 28% of the seats. Even with its Bavarian ally, the Christian Social Union in Bavaria, the two parties together account for no more than 35%.

[7] In the Italian Parliament, the Five Star Movement constitutes the largest bloc with 35% of the seats.

[8] In the Portuguese Parliament, the Social Democratic Party constitutes the largest bloc with 38% of the seats. The party is in opposition, and it is followed by the Socialist Party, which holds 37% of the seats.

[9] The fragmentation phenomenon also encompassed the Free Patriotic Union bloc and the Afek Tounes bloc, whereas the Popular Front bloc alone remained entirely stable, and the Ennahda bloc lost only one MP.

https://majles.marsad.tn/2014/assemblee/mercato

[10] The turnout in the vote on the whole bill among the blocs of the governing majority was 42.6% in the Ennahda bloc, 54.5% in the National Coalition bloc, and 60% in the Tunisia Project bloc.

[11] https://majles.marsad.tn/2014/simulation/scrutin

[12] Subsequently, the Internal Statute Committee did not examine Bill no. 64 of 2018, which the government submitted in tandem with the bill concerning the threshold.