The Battle Over Capacity and Standing Continues in Lebanon’s State Council

An extremely important battle is underway in the State Council over the standing or capacity to litigate. Whenever a citizen or group of citizens (a relevant organization) challenges an administrative decision for illegality or potentially violating the Constitution, the authority – be it the state, a municipality, or an influential private company – contests the legal capacity of the challenging party in order to have the case dismissed on procedural grounds before its details are examined. The more unjustifiable and morally indefensible these decisions are and – in practice – the greater their illegality, the more the authority resorts to this argument. Whenever the authority cannot convince public opinion of its decisions, it falls back on this position, as if to say that a citizen has no capacity or standing to defend public interests such as the environment, public property, or consumer rights. Apparently, any such action is an intrusion on the public authorities, which alone possess the capacity to defend public interest on behalf of all people.

Remarkably, this discourse finds promoters and – worse – an audience at a time when the institutions of representative democracy have become largely dysfunctional and most public administrations are inundated in corruption and practices that fawn on any influential person. Moreover, the public administration does not hesitate to employ it even though laws requiring citizens to defend the environment have been issued and the state has ratified international treaties obliging it to encourage them to expose and combat corruption (Article 13 of the UN Convention Against Corruption).

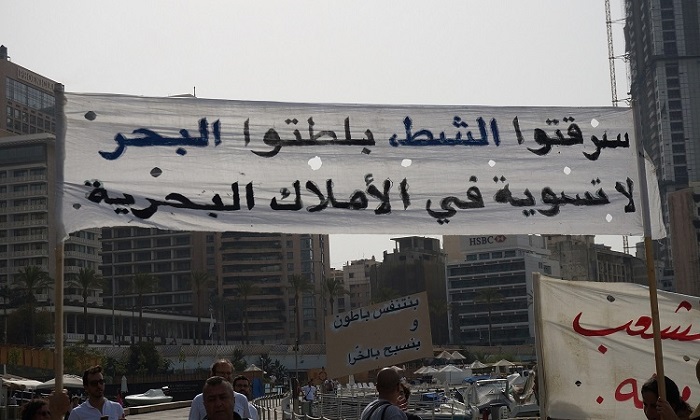

We have witnessed this battle in many cases, including the case that former minister Charbel Nahas and his associates filed against the continuation of tax collection, borrowing, and spending in the absence of state budget laws between 2006 and 2016. It also came to the fore recently in the cases challenging the decrees permitting the occupation of maritime property in Naameh and Zouk Mosbeh, and the Council of Ministers decision granting an administrative grace period to quarries operating illegally. Citizens, it seems, have no capacity to defend public interest in court. In all these instances, the citizen is an intruder and powerless. To show the scope of the problem, this article will elaborate on the cases of the Eden Bay hotel’s building permit and the “secret decree” pertaining to the Dalieh region.

“Lack of Capacity” is the Magic Word for Resuming Eden Bay’s Construction

The case of the construction of the Eden Bay hotel on Ramlet al-Baida – the last breathing space on the sea for Beirut residents – has become highly symbolic in public discourse. While the company was initially compelled by judicial decisions to stop construction, a magic word to induce the State Council to repeal these decisions quickly arose within all the circles concerned. This magic word – uttered first by the state, then Beirut Municipality, and then by the government commissioner – was “lack of capacity”. They claimed, sometimes in contradiction to their previous statements, that the plaintiff, namely the organization Green Line, lacked the capacity and standing to sue. While Green Line presented 11 arguments for annulling the permit (most of which were validated by the head of the Order of Engineers and Architects in Beirut), these parties’ responses generally ignored these arguments and were constrained to the issue of capacity and standing. Hence, for the public administration, the important thing is not proving its compliance with the law but denying the role of a citizen – any citizen – to defend the environment, public property, or any other public interest. In the public institutions’ view, the issue of defending public property and public interest against an influential company had magically transformed into a matter of defending the state’s monopoly over the protection of public interest against all its citizens.

The first sign of this stance was Beirut Municipality’s contestation of Green Line’s capacity to sue. In this regard, the municipality had no qualms about contradicting its previous stances contending that environmental organizations do have the capacity to litigate to protect the environment, as though capacity may be accepted or rejected based on interests or mood.

The Cases Committee, the state’s representative before the State Council, followed suit even though it had previously supported the case’s merits. Remarkably, it dedicated eight pages to explaining its denial of Green Line’s capacity and just half a page to denying all 11 arguments without any explanation. It expressed this stance in a very telling exclusionary discourse: “These maritime public properties have their authority competent to protect them, and it is the Directorate General of Land and Maritime Transport as it represents the state – their primary owner – in their protection and defense and the prevention of any encroachment upon them. Nobody else, be they a private or public legal person or a natural person, has the right to take this power for themselves and supplant the state”. This proposition – which serves as a lesson on the orientations and concerns of the state – speaks for itself. Instead of thanking the citizens for defending public property, the state chose to litigate against them in order to have them removed from the case. One of its practical consequences is that any encroachment on public property can be shielded from any case filed by any citizen [and left unchallenged] by ensuring that the aforementioned directorate is complicit or at least neglects to take any action to stop it. The Cases Committee’s zeal in defending the exclusivity of the state’s power to defend maritime public property is even more deplorable because the state administrations have already proved incapable of exercising it. References to thousands of encroachments on public property have accumulated in their records over the past decades, yet they have been totally unable to confront or put a stop to these encroachments. Hence, by restricting the defense of public property to state administrations, the Cases Committee seems to be seeking to give them a discretionary right to defend or not defend it and, in practice, to fuel their practices of power-sharing, fawning, and corruption.

Despite the egregiousness of this stance, the government commissioner, on his part, had no qualms about going back on his earlier request that the building permits be suspended and demanding that the suspension be revoked because of a lack of capacity and standing.

These coordinated stances reveal the shape of the coming social confrontation: the defense of the right to litigate, however painstaking it may be, in the face of the state administrations’ chronic failure to protect public interest. Public property must not remain abandoned, and nobody should think that defending the environment is a mere sentimental or romantic issue rather than an issue in which they are bound by laws to intervene.

The Acrobatic Governor

While opposing changes to Dalieh’s landscape, activists of the Civil Campaign to Protect the Dalieh of Raouche discovered Decree no. 169 issued 21 October 1989, now known as the “secret decree”. This decree sought to change the system in effect in the so-called “Zone 10”, whose periphery includes Dalieh, by freeing property owners wanting to erect facilities from having to relinquish 25% of their properties’ area to Beirut Municipality. Worse, the decree returned property previously transferred to the municipality under this system to their original owners free of charge. The decree’s main beneficiary was the owner of the property bordering Dalieh, who had relinquished 25% of it in the early 1980s after obtaining permission to build the Merryland hotel (where Movenpick Hotel stands today). The area abandoned under this decree was approximately 5,400 square meters, which is worth at least US$50 million.

Nine months after Beirut Municipality was tasked with delivering its opinion on this case, it filed a detailed submission fully supporting the plaintiff organizations’ demand that the secret decree be annulled for violating the law. The submission extensively defended environmentalist organizations’ capacity to defend public property and the right to access the sea. The municipality also invoked the Environment Protection Law, particularly articles 3, 29, and 33. It concluded its defense by stating that, “It is clear from the above texts that the law has granted every citizen the capacity to sue to protect the environment and conserve its natural resources, including maritime public property and coastal regions”.

In parallel, some of the plaintiff organizations in the secret decree case engaged in denouncing the permit that Beirut’s governor granted (in his capacity to represent the municipality) for the construction of the aforementioned Eden Bay hotel. Subsequently, the municipality had no qualms about contradicting its stance in the secret decree case by arguing in the Eden Bay case that environmental organizations have no capacity or standing to defend maritime property. Then, in the biggest surprise yet, it backflipped in the secret decree case itself, claiming that the environmental organization has no capacity or standing. When the campaign reminded the municipality of its contradictions and the principle that a party may not resile from its previous claims (i.e. estoppel), the municipality justified itself with an excuse even worse than the backflip: “A defense of the applicant’s stance in this case would influence or be adopted as an argument against [the municipality] in pending cases [a reference to the aforementioned Eden Bay case]”.

Hence, the municipality justified its reversal not on the basis that its convictions had changed but via the pragmatic argument that it must avoid having its words used against it in the Eden Bay case. Clearly, the municipality places more importance on fortifying Eden Bay’s building permit against any judicial accountability than on its duty to defend its public property as a precursor to recovering thousands of square meters of stolen property worth at least US$50 million. The municipality thereby appeared to have no qualms about covering up the plundering of public wealth to preserve the shady deals it had recently made. The transformation of these stances in and of itself constitutes a definitive argument for expanding our acceptance of capacity and standing to challenge decisions by the public administrations.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Lebanon, Public interest, Public property, Corruption, Eden Bay