‘Settling’ Beirut: Residents Rebel Against the Club Clamor in Hamra

There are some resources that we hold in common, such as the air we breathe and the water we drink. We take them for granted, but their widespread availability makes everything else we do possible. […] Just as clean air makes respiration possible, silence, in the broader sense, is what makes it possible to think.

–Matthew Crawford, The World Beyond Your Head

Open your windows and listen to the sounds of the city. What do you hear? Listen well. Are you in a residential or a commercial area? Are you by the forest or the sea, or are you surrounded by cement residential buildings? What sounds arise from the part of the city wherein you live?

Whoever walks in Beirut’s streets is inevitably hit with the sounds of incessant car horns, and the constant construction work scattered across the city. The clamor in Beirut has reached the point of becoming an inseparable part of the city’s identity. Beirut is not a quiet city. Beirut is the city of constant ruckus that encroaches on our daily life; to the extent that we now surrender to it, and we do not think seriously about the repercussions on our standard of living, and on our physical, mental, and intellectual health. If clean air allows us to breathe and hence continue living, then silence is what allows us to think. The benefits of silence to our lives are enormous. While those benefits cannot be evaluated using the traditional tools of econometrics, silence in a certain environment does inevitably and directly promote creativity and innovation. According to contemporary American philosopher Matthew Crawford, becoming learned individuals requires us to consume significant amounts of this silence.[1]

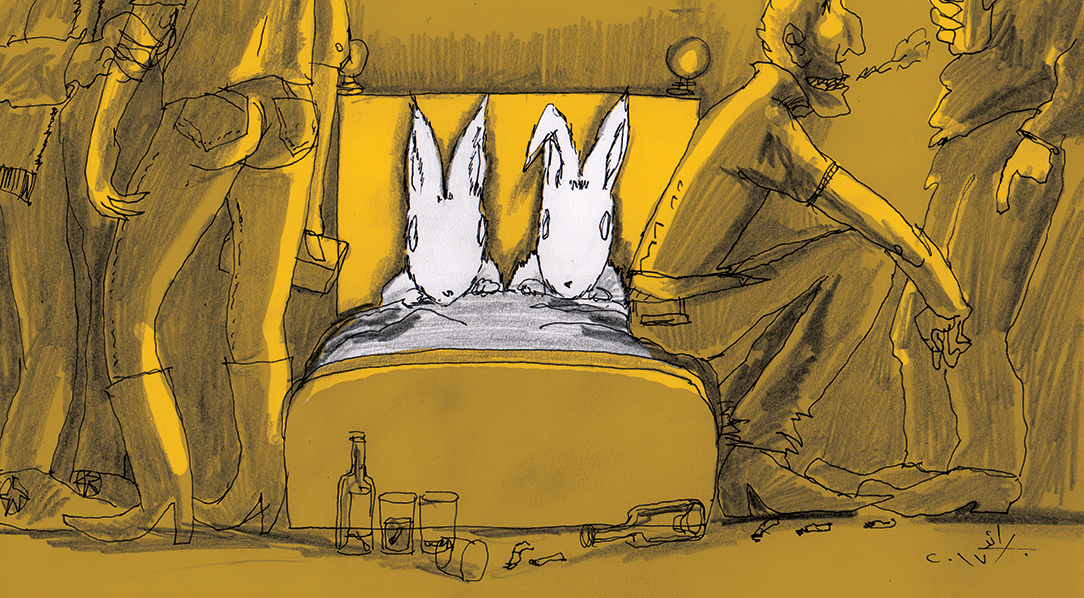

Now, imagine yourself living in a street interspersed with pubs, bars, and nightclubs. All your nights are governed by the stress of the soirees and parties hosted by those pubs, the movement of the pubs’ patrons and their cars, and valet parking. This is something that neither Gergi Bashir nor Ahmad Baydun have to imagine, for they have both lived on Makdessi Street, parallel to Hamra Street in Beirut, since before the civil war broke out in the mid-1970s. In fact, in the late 1950s, the Hamra district (i.e., Hamra Street and the streets parallel to it) became famous for its commercial activity and nightlife. This is especially because of the establishment of several cafes and night-time hangouts, and because Beirut’s youth and intellectuals of the time frequented it. Bashir and Baydun have become accustomed to the area’s activity and the subsequent encroachment of a certain level of noise on their daily lives.

Around two years ago, a number of restaurants and contiguous pubs opened on Makdessi Street itself just meters from Bashir and Baydun’s homes. Most of these pubs are in “The Courtyard”, an open square opposite the building wherein Bashir lives. At the center of this square there are four or five restaurants and pubs that lack stone or cement roofing; they are essentially uncovered squares delimited only by nylon or plastic curtains. They reflect a conception of nightlife that has recently developed in various areas of Lebanon, especially in the Hazmiyeh and Dbayeh areas. Because of their open structure, the noise of their nocturnal activity reaches absurd levels for a residential area such as Makdessi Street. The loud music, voices, and excessive noise emanating from those pubs due to their speakers, and the ruckus produced by their patrons and valet parking workers deprived local residents including Bashir and Baydun of the tranquillity essential to their rest, thinking, and sleep. It therefore caused physical, psychological, and moral harm. “They were threatening our right to live”, state Bashir and Baydun, adding that the pubs’ owners were “going about their business as though we didn’t exist”.

To address the issue, the residents first turned to Beirut’s governor, Judge Ziad Chbib. On January 1, 2016, they signed a petition demanding that he apply the laws and regulations stipulating the conditions for operating restaurants, pubs, entertainment venues, cafes, nightclubs, and discos within residential and non-residential areas.[2] However, the governor handled the issue in a very passive manner disproportionate to the harm caused by the operation of pubs that don’t have a valid operating to begin with. While the Department of Classified Establishments in the Beirut municipality issued warnings to the establishments mentioned in the petition,[3] there was no serious follow-up. None of these pubs complied with the warning and the excessive noise continued to pervade the area, including Bashir and Baydun’s homes. Bashir and Baydun then turned to the Beirut police detachment but found its handling of the issue to be “poor”: “They said [to us], for example, that the business owners are right, that the law allows them to operate until midnight during the week and until 1:00 am on weekends, and that there is no specific noise limit. We then contacted the director-general of the Ministry of Tourism, and while she promised to do good, we saw no mentionable results on the ground.”

“Most of the local residents were scared to take the step of resorting to the courts, given the rumors that the pub owners were protected [by influential forces]”, recalls Baydun. The duo therefore decided to go it alone on behalf of the neighborhood, to put an end to the pubs’ encroachment on their right to rest and hence to housing. “We resorted to the courts because of our civic spirit toward handling the issue,” Bashir explained. Hence, on May 9, 2016, they filed a case with the summary affairs judge in Beirut against Bistro Pub, located in The Courtyard. They later added the neighboring pubs, including La Palma, Walkman, and February 30, asking the judge to ban them from playing loud music until they had presented proof that they had done the necessary noise insulation work signed by a sworn expert.

As soon as the owners of the aforementioned pubs received notification, the pubs’ attorneys and the manager of The Courtyard called for a reconciliation meeting which was held in Bashir’s house. I attended the meeting as both Bashir and Baydun’s attorney, and two main things caught my attention. The first was the game of exchanging accusations that the pub owners played among themselves (a game that would crystallize as the case stretched on over the following months). Each pub owner accused the others of turning up the music to attract customers and thereby “combat” (i.e., compete with) the other pubs. The second was the insistence of Fatima, Gergi Bashir’s wife, on recalling the days of their youth when they went out at night to cafes and entertainment venues in 1970s Hamra. She did so in earshot of the pub owners sitting in her parlor, as though she was attempting to make them understand that the case is not aimed at curbing their commercial activity. The couple is not against nightlife or having fun, but they also assign paramount importance to the rights of others to peace and quiet, just as the youth did in the 1970s.

Following this meeting, and given the pledges that the pub owners made about installing soundproofing and taking other measures to limit the noise, the residents remained patient for numerous months to no avail. The pubs continued raising their nightly volume and continued to turn the speakers towards the street to attract customers and, in the process, vie with each other. After the judge assigned an expert to measure the noise in the street, in front of the pubs, and even in Bashir and Baydun’s homes, and the volume was found to be several times higher than the legal limits for those late hours of the night and in such residential areas, they decided to resume the case proceedings.

Subsequently, Judge of Urgent Matters in Beirut Jad Maalouf decided to call the parties to a reconciliation meeting in his office in Beirut’s Adlieh area, in an attempt to find a prompt and amicable solution that suited everyone. However, during that meeting the pub owners unfortunately took the same approach that they had adopted during the first reconciliation meeting in Bashir’s house: they fired accusations at each other, and ultimately repeated false promises about adhering to a noise limit. Hani Hashem, the owner of February 30 and Walkman, even signed a legal reconciliation agreement that the parties formulated together, wherein he pledged to adhere to a noise limit under pain of a fine of LL20,000,000 [US$13,220] per violation.

After a second expert report was issued concluding that the pubs were still not abiding by the pledges they made in Adlieh, Judge Maalouf decided to personally go with the expert to inspect the pubs’ activity. He found that the noise level of the pubs, including the two that had signed the reconciliation agreement (February 30 and Walkman), was still several times higher than the legal limit. The inspection established that these two pubs intentionally violated the agreement twice that night, once before the judge arrived and once just minutes after he left. Consequently, Bashir and Baydun filed another case against these two pubs, demanding that they pay an advance on the penalty clause in the aforementioned legal agreement.

Facing the gross contempt that this sum of violations showed toward the right of the residents to peace, and quiet and even toward the judiciary itself as the pubs had reneged on the pledges they made (and signed) before it, Judge Maalouf issued a first ruling on February 6, 2017. This ruling compelled the defendant pubs to take the necessary measures to reduce the noise to within the legal limits, under pain of a fine of LL15,000,000 [US$9,910] from each one per day of violation. The judge cited the World Bank Group Environmental, Health, and Safety Guidelines as well as decision 51/1 issued by the minister of environment on July 29, 1996, which set the noise limit in commercial and administrative areas and in the city center after 10:00 pm at 55 decibels, thereby consecrating the residents’ right to rest. The ruling stated that, “whereas, the right to property and the right to housing as a matter of course entails the right to enjoy the property or residence for the intended purpose, and within the conditions that ensure physical and psychological integrity, and provide rest and health to the right-holder”. It added that any encroachment on these rights is “an encroachment on the right to property or housing as it severely diminishes the ability to enjoy said two rights”. Additionally, in the second case that Bashir and Baydun filed against February 30 and Walkman for violating the aforementioned legal agreement, Judge Maalouf issued a second ruling on February 24, 2017, compelling the two pubs to pay an advance of LL100,000,000 [US$66,090] on the compensations.

“The court did its work professionally and fairly […]. The judge exhausted all available means to compel the pubs to obey the legal conditions before he issued his ruling on the case”, Baydun says. They add that the noise began to drop after the ruling. According to them, the next stage is “turning the issue into a public debate issue transcending the case that we won”.

The reality is that the right to silence is absent from public debate today. Its importance on our quality of life is enormous, for it is the key component of the thought process, as I said earlier. Rectifying the issue is very simple: all it takes is to distance oneself a little from the center of the city to experience the benefits. I myself experienced this recently with the relocation of our office from Tabaris square in Ashrafieh, which is noisy throughout the daytime, to one of the quiet streets branching off Badaro Street. Crawford’s concerns about silence becoming a valuable private commodity traded in modern economies are legitimate.[4] Silence is not a luxury; it is a basic right extending from the right to housing. Here, the word ‘settling’ [taskin] has two basic meanings [to settle an area, and to settle something down] that contribute directly to a responsible urban development strategy.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] Matthew B. Crawford, The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, First Edition, 2015.

[2] Specifically, Decision no. 262 issued February 25, 2009, by the minister of interior and municipalities, and the minister of tourism.

[3] An-Nahar, January 5, 2016.

[4] Matthew B. Crawford, op. cit.