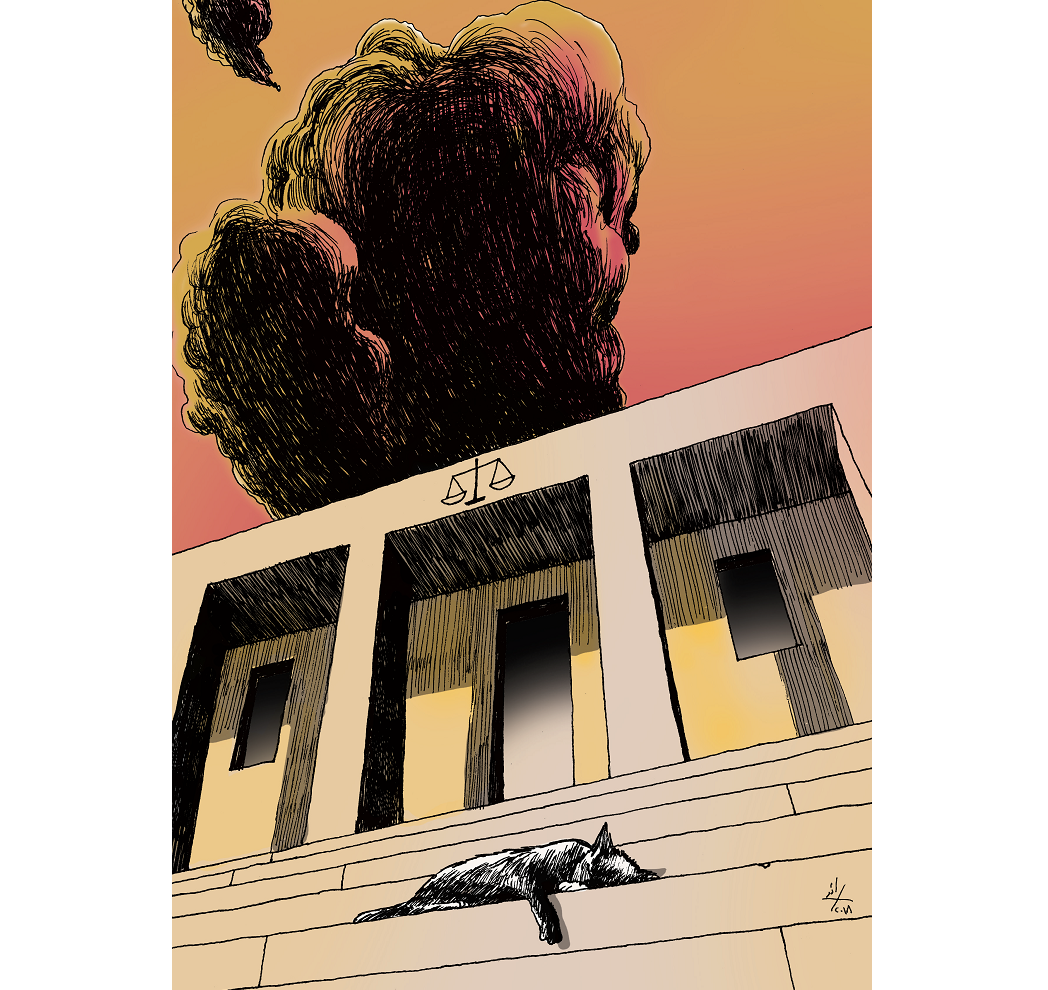

Public Hearings: To Give Lebanese Administrative Justice a Soul

“Publicity is the very soul of justice” (Jeremy Bentham, 1790), yet this soul is missing from Lebanese administrative justice. The current law regulating the State Council stipulates no real public hearing. The procedures that occur in the one and only court of the administrative judiciary are almost exclusively written: from the request filed by the applicant, to the briefs exchanged by the parties, to the report issued by the rapporteur judge, to the government commissioner’s written conclusions, to the case file referred to the ruling bench, which deliberates in secret. The only public hearing stipulated by the law is the one to deliver the final decision, and it only exists on paper. This is a sorry state of affairs.

Beyond any metaphysical or romantic notions, does the absence of public hearings in the State Council constitute a real flaw in Lebanese administrative justice? It is tempting to think not. After all, written procedure can, except in extremely urgent cases, perfectly allow quality judicial debate provided that it is, of course, adversarial. Moreover, if no argument can be added orally, why waste the ruling bench’s time by making it listen to the parties repeat what it has already read? This reasoning is especially compelling because in the Lebanese State Council, there is no need to convene a public hearing to view the government commissioner’s conclusions. Unlike in French administrative law, all these conclusions, as well as the rapporteur judge’s report, are sent to the parties before the bench deliberates, and the parties can respond to them with written comments.

However, this cold, technical perspective contending that public hearings in administrative procedure are pointless ignores an essential matter, namely that the hearings fulfill objectives far beyond mere procedural efficiency. It is these objectives that justify the inclusion of the right to a public hearing in the main international texts on human rights, particularly two cited by the Lebanese Constitution’s Preamble: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. According to the European Court of Human Rights,

The publicity [of hearings] protects litigants from secret justice occurring outside of public oversight. It is also one of the means of preserving confidence in courts and tribunals. Via the transparency that it gives to the administration of justice, publicity helps to achieve the aim of Article 6 Paragraph 1 [of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms], namely a fair trial, the guarantee of which constitutes one of the principles of any democratic society.

Hence, public hearings are first and foremost an indispensable tool of democratic oversight. Justice, including administrative justice, is delivered “in the name of the Lebanese people”. For this expression, which heads the State Council’s rulings, to be more than an empty slogan, citizens must have the right to see what is done in their name – not only the ruling, of course, which must be public, but also the debates that precede it. This is one of the conditions of informed democratic oversight. Public debates, wherein each party confronts the other’s positions in the presence of the interested public, civil society representatives, and – most importantly – the press, allow people to know the arguments raised and read the subsequent ruling critically. Conversely, such a reading is difficult when we are ignorant of the details of the debates that preceded the ruling except for those leaked by litigants.

Hence, public hearings contribute to public confidence in the judiciary. We cannot simply ask litigants to trust the judiciary; we must give them reasons to do so. While guaranteeing the judiciary’s independence and impartiality is essential in this regard, other guarantees are no less important. In administrative procedure, such guarantees include reassuring litigants that they have been heard. The members of the bench know that they have conscientiously studied the case file, particularly the pleas presented by the applicant, but the applicant may naturally and legitimately doubt this. Even if the applicant confirms that the rapporteur judge studied the file by reading that judge’s report, they cannot be certain that the other judges on the bench did the same. Did they have the time and the will? Or did they spare themselves the work by relying on their colleague’s analysis?

While public hearings may not remove this doubt entirely, they at least neutralize most of the negative effects that applicants rightly or wrongly fear. They also allow the applicant to address all the bench’s members orally to remind them of the main points in his or her argument or comments on the rapporteur’s report and the government commissioner’s written conclusions. Regardless of the quality of the Lebanese State Council’s rulings, the adage says that “justice is not only to be done but to be seen to be done”, and oral proceedings can only strengthen publicity. This is the price paid for confidence in the judiciary.

These two reasons – democratic oversight and litigants’ confidence – render public hearings a fundamental right. The bill to reform the administrative judiciary that the Legal Agenda is proposing enshrines this right while still allowing the bench’s president to, as an exception, order a closed session if necessary to protect public order, respect peoples’ privacy, or keep legally protected secrets. The president is also responsible for policing the hearing. According to the bill, the hearings will occur as follows: the rapporteur briefly presents the case; the public rapporteur (the new name for the government commissioner) then recites his conclusions; finally, the parties present their oral observations. While the public rapporteur presents their conclusions orally, they may choose to respond to any observations that the parties previously presented to them in writing. The parties may also, when expressing their observations, reply to the public rapporteur’s responses orally. Moreover, in the hearing, the members of the bench may ask the parties questions to clarify particular points, provided that the principle of impartiality is not infringed.

Administrative justice affects public life. Film censorship, public procurement, the occupation of maritime public property, the naturalization of foreigners, local election results, the protection of cultural heritage, appointments in top public positions, and the operation of quarries are all controversial issues that may fall under the administrative judiciary’s jurisdiction. Such justice cannot be rendered from an office. Rather, administrative justice must have a soul, and public hearings would help to give it one.

Keywords: Lebanon, Administrative justice, Public hearing, State Council