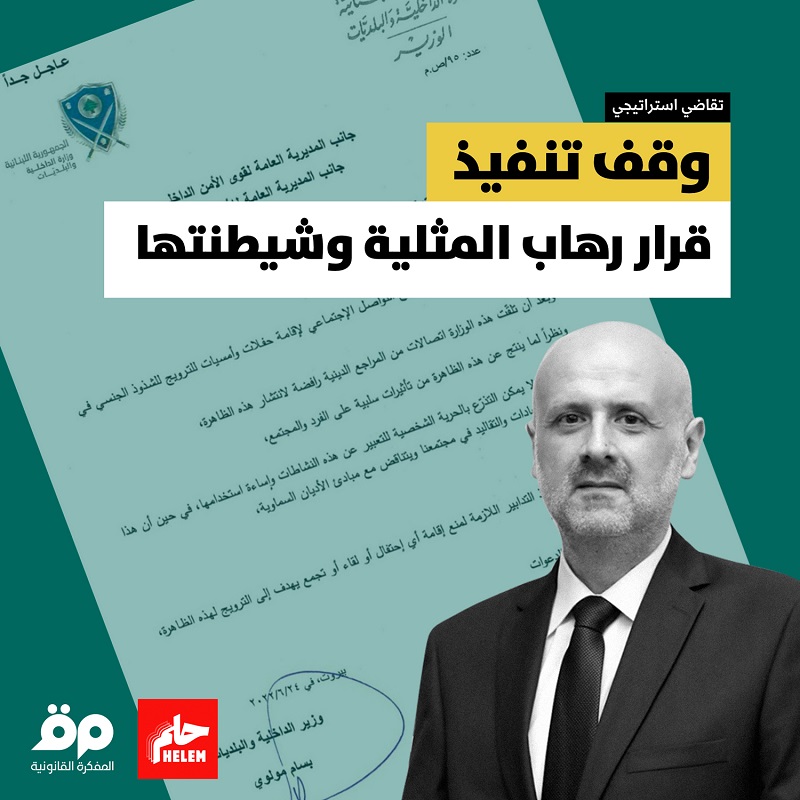

Morocco’s Judges League (1961-1965): Reviving a Forgotten Anti-Colonial Legacy

The Moroccan Judges Club which was established after the inception of the 2011 Constitution, embarked on an extraordinary journey to defend the independence of the judiciary and of judges. In light of the discussion surrounding the Club's work, it may be very useful to shed light on the experience of a pioneering judicial movement that took place on the eve of independence, as it relates to the 1962 Constitution. Despite the richness of that experience, it is largely absent from [public memory] due to the dearth of documentation of that period.

This article seeks to recall the beginnings of this nearly-forgotten chapter in the history of contemporary Moroccan judiciary, particularly, during its early heydays (1961-1965). Given the immensity of such a task, this article is more of a solicitation for judges who witnessed that period, and for those who possess information or documents relating to it to come forward and share their knowledge with the new generation of judges who are largely unaware of that history.

In the Wake of Colonialism: The League’s Judges and Organization

Colonialism left Morocco’s judicial system in tatters for much of the first decades of independence. Protectorate authorities [Spanish and French] in the north and the south managed to undermine the Moroccan judicial system. They established courts of law for foreigners, with foreign judges, as well as other courts, namely criminal, that were managed by administrative authorities and which did not draw on any law. In certain regions, especially rural ones, they also established customary courts presided over by notables under the supervision of the protectorate authorities.

This entire process was a systematic attempt by colonial forces to denigrate the Moroccan Islamic judiciary whose history was deeply-rooted in Maliki jurisprudence. In addition to restricting its jurisdiction to civil matters concerning Moroccans in urban areas, the judiciary was denied the material means necessary for its operation. Protectorate authorities made the judges receive their wages from litigants, and then turned them into state employees.

The number of Moroccan Sharia judges who formed the nucleus of the independent Moroccan judiciary was not sufficient to serve the entire country. Due to their fiqh (Islamic Jurisprudence) background and their semi-exclusive specialization in personal status cases, they were also not sufficiently qualified to apply the most important branches of modern law that were in force at the time and written in French.

The judiciary’s independence did not eliminate this duality in the judicial system, with Maliki jurisprudence continuing to be based on multiple legal sources, and with a modern legal tradition expressed in French language. Foreign judges continued to be present, even in the Supreme Council. Moroccan judges looked at these laws with suspicion, with most of them calling for the adoption of Maliki jurisprudence as a source of law, even in reference to normal transactions [muamalat].

In return, a few judges adopted a different position and called for excluding Islamic jurisprudence and establishing modern laws. This intellectual trend had a relatively larger weight in the urban societies of Morocco post-independence.

Despite their conservative and traditional nature, Moroccan judges of the independence era established a professional association on a modern basis. The tough working environment they found themselves in pushed them towards uniting together.

In May 1961, and within the framework of the 1958 royal decree on association, the first constituent conference was held in Rabat and the first professional association for judges in Morocco was formed under the name of the Judges League. According to its by-laws, the League's objectives were summarized as follows:

Creating closer bonds of friendship among the Monarchy's judges;

Working to guarantee the rights and interests of its members, as well as protecting their dignity as members of an institution held in high regard;

Spreading the noble ideals to which the League adheres, namely: Justice, integrity, selflessness, and human dignity; and

Strengthening cultural development.

The League's [governing] structure was composed of a conference, a national bureau, and a chairman elected by the conference. It held five regular annual conferences in various cities between 1961 and 1965. Subsequently, it held only four conferences; one in Fez in 1971 and three others in Rabat in 1967, 1979 and 1981.

The League published -albeit irregularly- an annual journal with the same name. Out of a total of 22 issues, the first six were published between 1964 and 1966, and addressed various professional and legal matters including briefings on the first five conferences. The remaining issues were published between 1981 and and 1987. Issues published in the latter period did not include articles on professional issues. They also did not include any reference to professional demands or conferences starting in 1967.

The League completely disappeared in the historic record after that. The last official document referring to the League was the decree setting up the National Human Rights Council in 1990, which mentioned it as one of the Council's components representing associations and organizations of class “B”.

The League’s Demands

Thanks to the League, the years 1961 to 1965 witnessed a dynamism among judges. The establishment of a professional association was in itself an important event, as stated by the former king late-Hassan II when he met with the League’s Bureau and its chairman on November 27, 1965 and credited the judges themselves for setting up the League.

The association articulated its demands in its first five conferences in the form of requests that fell within one of two categories: demands to defend the independence of the judiciary and to build its authority, and demands relating to the professional status of judges, which were linked to the question of judicial independence.

1. Independence of the Judiciary

The League's third conference, held between September 20 and 23, 1963 in Tangier, stated the following in its first set of demands (copied here verbatim):

“The conference regretfully notes that judges in some parts of the kingdom were subject to improper acts violating their dignity. We [thus] request the following:

First: Overseeing the implementation of the principle of the separation of powers.

Second: Making all the necessary investigations prior to searching a judge's residence or interrogating him.

Third: Alerting the police that they need to submit their reports to the concerned judicial departments before taking measures that bears on the judge’s person or involves his place of residence.

Fourth: Refraining from relying on general secret reports submitted by the administrative authorities against members of the judiciary.” (A similar demand was presented in the fourth conference held in 1964.)

In the same vein of safeguarding judicial independence, the League tried to protest the power to second judges, which was an exclusive prerogative held by the minister of justice. On April 10, 1964, the League’s Bureau submitted a complaint to the justice minister to protest some transfers he made among judges. It partly read as follows:

“Out of the confidence entrusted upon us as representatives of the judges, we believe that it is our duty to inform Your Excellency that the rotations you made among judges have caused a wave of resentment among them. These decisions caused them a great deal of concern over their destiny and caused them to question the necessary guarantees of their independence, granted to them by the Constitution. We persistently ask you to reverse these decisions and keep those concerned in their positions, pending the Supreme Council's meeting.”

In the League's fourth and fifth conferences, the judges also requested the creation of a special set of regulations to govern the rotation of judges. They asked that these regulations take into consideration the wishes of the judge first, and that the transfer should be done through the Supreme Council as stipulated by the Constitution that magistrates may not be transferred.

2. Professional Demands

The third and fourth conferences saw the listing of a number of professional demands, with judges speaking of “the state of anxiety judges are living through which does not provide comfort, tranquility, and self-sufficiency”. The first constituent conference also focused on the material conditions of judges. The report of the fifth conference held in Fes in October 1965, demanded compensation for the judges for fulfilling their tasks, as well as a two-month annual vacation. The report noted that judges due for promotion “attained their right after more than three years of waiting”. The conference also announced the issuance of “special passports for judges”.

The League's Bureau was active during this period through direct and periodic meetings with justice ministers or their assistants. Bureau members sought to defend the requests made by the conferences. They highlighted some issues like the need for the separation of powers following abuse by some government officials, or discussed the financial status of judges to “guarantee the minimum and necessary level of decent life”.

Published documents and testimonies show that the most important cause fought for by judges through the League was an initiative to Arabize, 'Morocconize', and unify the Moroccan judiciary during the third conference in Tangier in September 1963. The League continued to defend this issue until it was approved in accordance with the Morocconization, Arabization, and Unification Law of January 24, 1965.

3. Relations with Institutions

The initiative of Morocconization, Arabization and unification may have been a reaction to the judges' feeling of their inability to implement the laws properly due to three [interrelated] factors: the foreign language the law was written in, the judges’ perception of the law as a legacy of colonialism given the continued presence of foreign judges in courts, and the presence of certain powers that had a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

Judges worked, through the League, to contact parliamentarians and inform them of the problems plaguing the Moroccan judiciary at the time. These contacts culminated for the first time in the history of modern Morocco, with the Parliament's Committee on Justice and Legislation granting judges an audience – the latter represented by League Chairman Hamad al-Iraqi. Al-Iraqi presented the judges' point of view regarding the need to unify, Morocconize, and Arabize the Moroccan judiciary. The League won the recognition of the committee chairman and the understanding of its point of view.

When the law was discussed in parliament, the justice minister opposed it in both chambers of parliament. This did not, however, prevent its approval after the late-Hassan II endorsed it within the framework of fulfilling national sovereignty. The approval of the law came as a breath of fresh air to judges, who were required at the time to mobilize their efforts for the purpose of extending national sovereignty over the judiciary. The League's fifth conference was held in 1965 in these circumstances under the slogan: “Conformity of Judicial Legislation and Organization with Moroccan Reality”. The new law was scheduled to be in effect as of January 1, 1966.

The conference was attended, and addressed by the press attaché of the Arab League's permanent office for coordinating Arabization efforts. This was part of the League's efforts to educate judges in the field of Arabic legal and jurisprudence terminology. An agreement was concluded between the two parties to this effect.

The League also organized cultural meetings among judges during which they revived the old judicial heritage of Morocco. More importantly, the League aspired to be more open in the future and engage with the public in order to utilize media outlets to promote awareness among people of the current laws. The League also gave space in its journal during the period of 1961 to 1965 to judges who wrote on legal or professional issues in a bold and prolific manner.

The meetings with the justice minister continued without hurdles. On February 16, 1964, one meeting between the League's Bureau and the minister on the second day of Eid Al-Fitr lasted five hours. The meeting examined the petitions of the third conference and the judges' living conditions.

In the fifth conference report in 1965, League Chairman al-Iraqi stated: “God is our witness, we were never, in our work in the League, selfish, fictional, or people of slogans. Rather, we were always realistic and logical. Our work was always aimed at the general good and the interest of the country and the people”.

After 1965, however, the League seemed to be going out of steam. Morocco's political circumstances at the time may have been a factor. It would take another 50 years before its legacy of dynamism is revived with the establishment of the Moroccan Judges Club in the wake of the 2011 Constitution.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.