Morocco: Violence against Women Bill Makes Progressive Strides

A new bill to combat violence against women was recently announced in Morocco. Despite the importance of this initiative, the protests that coincided with its announcement led to overlooking many of the bill’s important legal rulings, such as those criminalizing a new set of actions. The latter became necessary in light of social, economic, legislative and even political transformations in Morocco.

Positive Aspects of the Bill

A framework law to combat violence against women has been one of the most pressing demands of the women’s rights movement in Morocco. Violence against women has indeed become a growing phenomenon, and as a result, there is cause for concern and a threat to the stability of the family in particular, and of society in general. Yet, none of the many amendments made to the Penal Code had been able to ensure significant solutions to crimes targeting women simply for being women, i.e., for considerations connected to gender.

A Conceptual Framework and Progressive Definitions of Violence

One of the main features of the new bill is that it made sure to set the conceptual framework for a number of terms used in its text, and provide progressive definitions of violence against women. It thus offers a near-complete list of the different types and forms of such violence: physical, psychological, sexual and economic. Most prominent of such definitions are the following:

Violence against women: “Any physical or non-physical (ma’nawi) act performed or denied on the basis of gender discrimination, entailing physical, psychological, sexual or economic injury for women.”

Psychological violence: “Any verbal abuse, coercion, threat, neglect or deprivation, either intended to undermine the dignity and tranquility of women and children, or intended to frighten or terrorize them.”

Economic violence: “Any act performed or denied of an economic or financial nature, causing or likely to cause injury to the social or economic rights of women and children.”

Moreover, sexual harassment was defined as “any persistent bothering of others in public spaces by deeds, words or signs of a sexual nature or for sexual reasons”.

Another feature of this text is that it does not just punish harassment of women by men, but rather, harassment in all of its forms. This appears in the use of the term “others”, which applies to both men and women. All forms of persistent annoyance of others in spaces open to the public are thus considered crimes, whether they are deeds, words or signs of a sexual nature or for sexual reasons.

Applying such a text may well give rise to difficulties in terms of proving the occurrence of harassment. Nonetheless, it represents a major step forward in the field of combating a phenomenon that has become rampant in practical terms. Among the numerous reasons for its prevalence is the collapse of the role of values within societies and the corruption of public taste. Another is the dominance of stereotypical notions that encourage and excuse harassment, in addition to views of women as inferior and as mere sexual objects.

Criminalizing Actions and Behaviors that had Remained Outside the Scope of Legislation and Represent Multiple Aspects of the Violence Threatening Women

Positive aspects of the new bill also include the first-time criminalization of a number of actions, especially those connected to the application of the Moroccan Family Code (mudawwanah). Until recently, this lack of criminalization had undermined all the protective features the latter had tried to consecrate for the rights of women in particular, and those of the family in general.

Refusing to return an evicted spouse to the conjugal home was thus criminalized, within the framework of Article 53 of the Family Code. Forcing or coercing women into marriage was also criminalized, with an increased penalty for cases also involving physical violence. Criminalized as well was any audio or video recording of women’s bodies, or of any act of a sexual nature or purpose, entailing defamation or insult for women. An increased penalty was also stipulated for the latter crime when committed by the victim’s husband, one of her parent family members, her legal guardian, or anyone with tutelage or authority over her or entrusted with her care. In the same context, theft, breach of trust and embezzlement between spouses were criminalized.

Creating a Legal Framework for Support Units for Female and Child Victims of Violence

Another positive aspect of the bill is that it created a legal framework to govern the work of support (takafful) units for female and child victims of violence. It recently formed in most Moroccan courts, with the purpose of providing prevention measures and protection from all forms of violence that women and children might be exposed to. There are currently about 86 such units in the whole country, whether in courts of first instance or courts of appeal, with their headquarters at the public prosecutor’s offices.

These units include members of all the different elements of the judicial body within a court of law. They consist of a representative of the public prosecution, an investigative judge, a judicial judge, a juvenile court judge, a court clerk and a court social worker. As the primary point of contact between the victims and the judiciary, they provide all the legal assistance needed to speed up the resolution of cases involving female and child victims of violence, in addition to medical and administrative assistance – all free of charge. They also make sure the judicial process is activated only as a last resort, after all attempts at conciliation between parties to the dispute have failed.

Laying Down New Protective Measures for Battered Women

Most prominent among these new protective measures for battered women are the following:

Temporarily removing the husband from the conjugal home, while returning the wife to the latter.

Transferring the victim and her children to reception centers, and sheltering them there in case of marital violence.

Preventing the offender from coming near the victim, her home, workplace or educational institution.

Putting the offender through psychological treatment when required.

Compiling an inventory of family belongings and property present in the conjugal home in case of marital violence.

Depriving the offender of weapons, if he owns any, in case of threats to use them.

Informing the offender that he is barred from making use of shared funds.

Negative Aspects of the New Bill

Negative aspects of the bill on violence against women fall under those related to form and those concerning content.

Objections Relating to Form

While the title of the bill speaks of combating violence against women, its contents surprisingly include rulings concerned with violence against both women and children. This is considered to perpetuate the prevailing stereotype about how to deal with women’s issues, by continuing to connect them to children’s issues. In fact, the bill includes texts criminalizing violence against parents, grandparents, guardians and spouses as well. In other words, the issue is not that of a bill meant to combat violence against women alone, but rather one that addresses domestic violence in general.

The bill is not aimed at drafting new legislation, but rather merely at amending a number of the rulings of the 1961 Penal Code. The text of the bill is therefore one that complements and amends current legislation, not one that constitutes a framework law to combat violence against women.

In many of its aspects, the language of the bill remains inconsistent with the evolution witnessed in the national and international legal field. A conservative language in itself, sometimes consecrates the same preconceptions and ready-made ideas about women’s issues. Sufficient to illustrate this is Chapter 495 of the new bill, which criminalizes infringing on the sanctity of women’s bodies – a text that seems to consecrate the same old stereotype about women [bodies] as a source of shame (‘awrah).

The bill’s philosophy perpetuates that of the 1961 Penal Code, as appears in the prevalence of security concerns and the prohibitive approach found in the text. Similarly, notions of male honor, family honor and the sanctity of women’s bodies seem predominant. The amendments introduced by the bill were unable to reduce the conservative nature of the original legislation, as appears in their continued use of the same previously criticized classification. The crimes of rape and sexual assault (hatk al-’ird) thus fall under crimes against public morals and decency. Meanwhile, the crime of gender discrimination falls under crimes of youth corruption and prostitution – renamed “sexual exploitation and youth corruption”.

In terms of content: Despite its positive aspects, the lack of a cooperative approach and the failure to consult those concerned and those interfering with its application, have had an impact on the content of the new bill. This can be seen on several levels.

The Preamble: Brief and concise, it neglects to mention the historical evolution of combating violence against women in Morocco. It also neglects to mention the role played by civil society and the national human rights movement in the field of combating all forms of such violence. Such a role includes providing legal defense and aid centers, in addition to producing memoranda, petitions and studies. Instead, the preamble focuses on government efforts, while ignoring all others. This clearly appears in its text, which states that the bill was the result of cooperation between the Ministry of Solidarity, Women, Family and Social Development and the Ministry of Justice.

The preamble also neglects to mention official or unofficial national statistics regarding the reality of violence against women. Such statistics would have helped explain the framework of this initiative, as well as its general and specific context.

The bill also remained silent about a whole set of issues that had been the focus of demands by human rights movements.

It did not criminalize marital rape, despite a growing number of complaints in this regard.

It ignored demands regarding the revision of rulings on abortion, to allow for the latter in certain cases, such as incest, statutory rape or rape resulting in pregnancy.

It did not criminalize child marriage without judicial permission, although it did criminalize coercion into marriage.

It did not set specific penalties within the framework of combating economic violence, which a large number of women are subjected to as a result of customs and traditions and the view of women as being inferior. Especially prevalent are cases of women being deprived of inheritance and shared land property – practices that are widespread within many social groups. Just as they criminalized theft, embezzlement and breach of trust between spouses, it would have been appropriate for legislators, in a separate text, to also criminalize maliciously seizing a woman’s inheritance and dividing it among relatives. These are crimes that target women simply for being women.

It did not stipulate the necessity of appointing workers specialized in the field of combating violence against women, whether as part of the judicial police, the courts or even the recently formed support units and committees. The selection of those charged with combating such violence is not based on clear standards. Rather, those who appoint them are given complete authority to select the members of committees and support units. The lack of specialized workers leads to inefficiency, especially when such workers are burdened with additional duties and responsibilities. The bill also neglects to stipulate compulsory and sustained training for members of those recently formed units and committees. It also fails to connect the work of committees and support units to any financial or moral incentives, which could have a negative impact on their intended productivity and effectiveness.

In terms of procedure and due process, the new bill did not care to introduce important changes to how cases of violence against women are dealt with. It did not care to set up a specialized court, or to create specialized branches or chambers within existing courts. It did not even require the latter to hold special sessions for cases of violence against women. Nor did the bill include an exception to the secrecy rule of the preliminary investigation, which would have allowed victims of violence to be heard in the presence of someone they trust.

The dominance of prohibitive concerns over a rehabilitative approach: The new bill merely criminalized a set of actions it considered as representing violence against women. It also increased the penalty in other cases, as deemed appropriate to their circumstances. However, it was not inspired by the need to try to rehabilitate those suspected of committing crimes of violence or harassment, having them submit to rehabilitation therapy sessions and applying the principle of rehabilitative justice.

It stipulated that a case that is dropped by the spouse who pressed charges would lead to discontinuing the penalty in certain cases. This is likely to consecrate the policy of impunity and normalize the phenomenon of marital violence. It could even legitimize the prevalent notions that place hundreds of obstacles to pressing charges of domestic violence before battered wives or women. The latter would become unlikely to take such a step, in order to avoid shame, out of fear of scandal, or to elude the family pressure or social pressure they find themselves under.

On the whole, the announcement that a bill on violence against women would soon be ratified is considered a positive initiative in and of itself. Nonetheless, its exclusion of those concerned with such a law from the debate can be held against it. Indeed, this new bill has emerged as completely separate from the accumulated results of years of work by civil society in the field of combating violence against women. As a matter of fact, it did not even make use of the assessment of existing support units at the court level, which had revealed a number of shortcomings. The latter are mostly due to the lack of specialization, full-time engagement, working means and incentives for those charged with the task. Additional problems include the difficulty of coordinating among the latter, and the absence of compulsion in the way the work is being done.

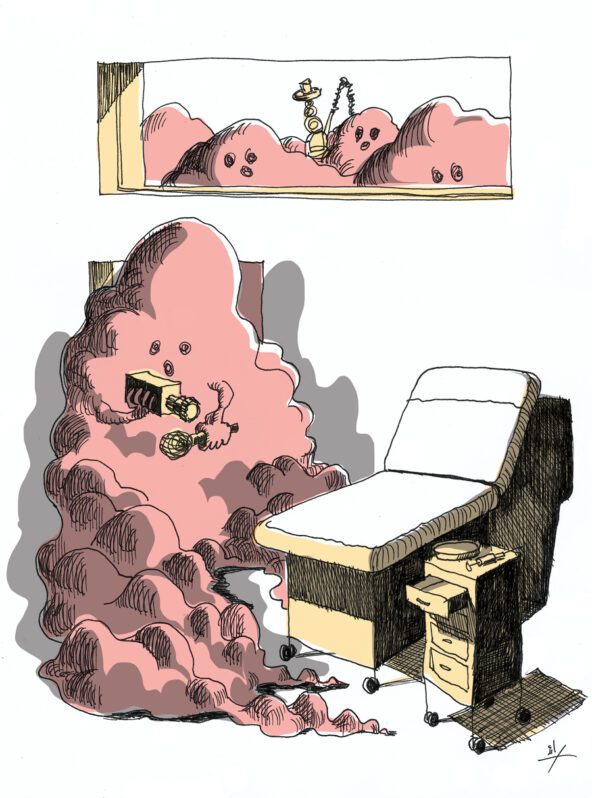

The media’s dealing with the bill constitutes another grave and important concern. The media has sometimes lacked professionalism and objectivity, and has reduced the entire discussion of the new bill to the issue of sexual harassment. Even the latter has been presented in a humorous and caricatured manner, and in no way consistent with the gravity of the issue of violence against women, or with the suffering it causes.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.