Local Councils in Egypt: Decentralization and the Dream of Political Action

The transitional articles of Egypt’s 2014 Constitution stipulated that a new system of local administration should be gradually implemented within five years of the date it enters into effect.[1] The system stipulated is based primarily on the administrative and fiscal decentralization of local administration units granted a large degree of independence and decision-making power. Hence, the Constitution explicitly obliges the executive and legislative branches to conduct elections for the local councils – known as “localities” [mahalliyyat] – by 2019, as well as to prepare the state’s administrative apparatus and train the workers therein on how to work with these councils in accordance with the new competencies the Constitution grants them. Nevertheless, the law regulating these elections has not yet been issued, nor has work been done to prepare the public for them in the first place.

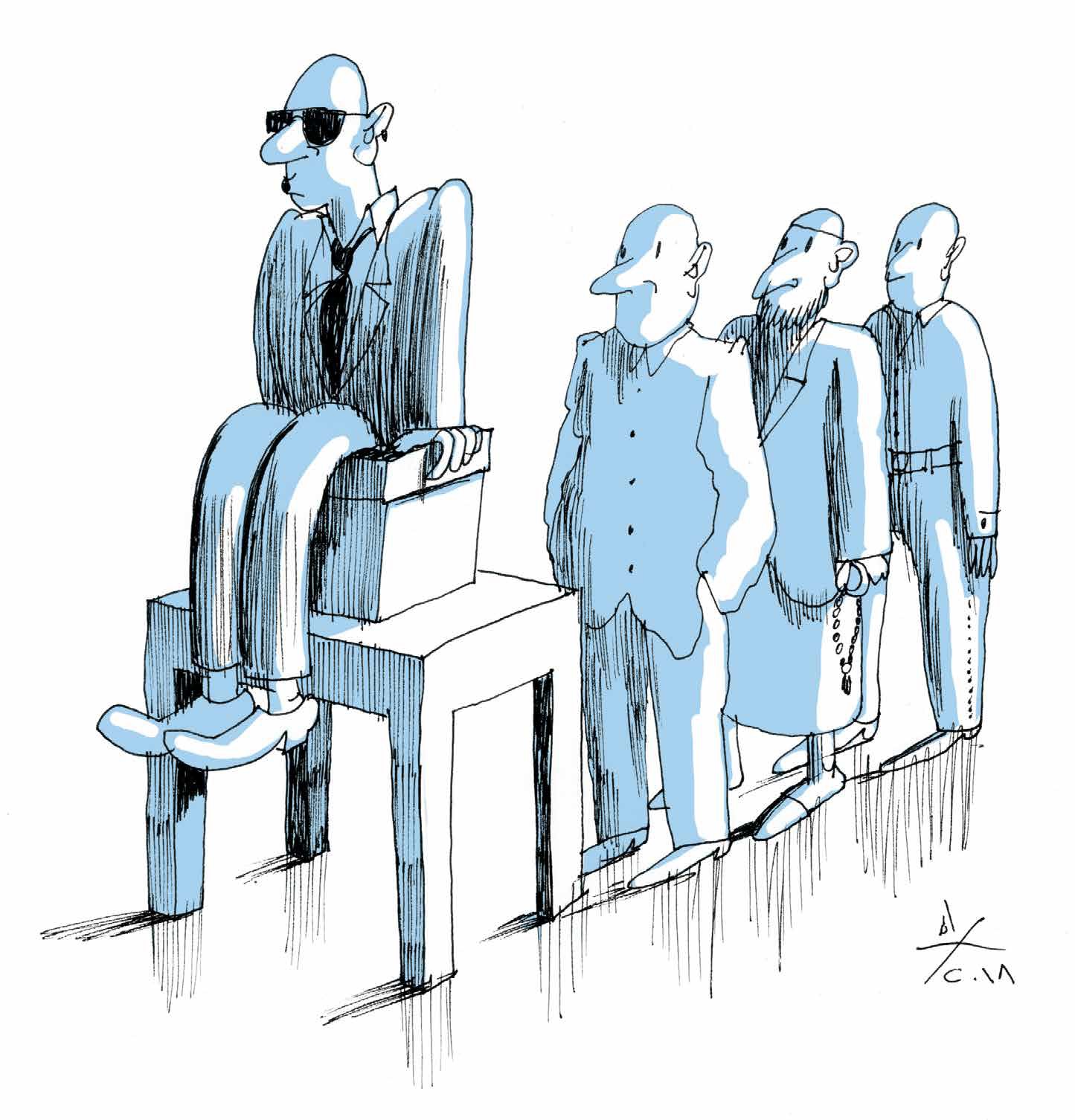

Rarely have the local councils been mentioned in the state’s discourse or even the various media outlets during the last few years. At the same time, there has been increasing restriction of the practice of any political action in Egypt, including: the crackdown on the work of legitimate political parties[2]; the burying of all independent union organizations before their establishment[3] and the fight against the organizations that already exist[4]; and the attempt to eradicate what remains of Egyptian civil society via the issuance of the NGO law, which limits the work of such organizations.[5] Hence, in this article we shall review the importance of the local councils in enriching political life in general and their role as a decision-making mechanism in the path to implementing decentralization.

The Structure of Local Governance in Egypt

Egypt was one of the first countries to adopt local administration.[6] This occurred in 1883 when Khedive Tawfiq Pasha issued the Egyptian System Law establishing the so-called “directorate councils” as branches of the central administration throughout the country.[7]

The 1923 Constitution then explicitly recognized local administration and explained the competencies and obligations of those councils.[8] Thereafter, all the successive constitutions adopted the same system. Among them was the 1971 Constitution, in accordance with which Law no. 43 of 1979 on the Local Administration System was issued, which is still in effect. Per the current 2014 Constitution, the local administration system is divided into “local governance units” with legal personalities, such as governorates, cities, village conglomerations, neighborhoods, and villages. These units are to have original competence to establish and administer all public utilities located within their limits and to exercise, within the confines of the state’s public policy, the competencies that the ministries exercise under the laws and regulations.[9] Each local governance unit is to have a “local council” – or a so-called “locality” – formed via direct election. This means electing for every governorate, city, neighborhood, and so forth a “local council” whose main function is to oversee the functioning of the local unit and track the performance of its staff and hold them accountable. However, the reality has always been different. For decades, the local councils were the greatest hotbeds of corruption, bribery, and squandering of public funds in Egypt, as the National Democratic Party, which ruled at the time, controlled the seats in these councils just as it controlled the entire state.[10] When the January 2011 revolution broke out, all local councils across the republic were dissolved. Since then, no new local councils have been elected. In the meantime, the government put forward several bills pertaining to the local administration system. The latest was presented in April 2017 and debated by Parliament’s Local Administration Committee.[11] However, Parliament has not yet officially announced the final version to be put to vote even though these elections must be held by 2019 at the latest, as we mentioned in the introduction.

Eight Years Without Local Councils

The ongoing postponement of the local council elections raised many questions about the reasons and justifications for it. During the Fifth Periodic Youth Conference held last May, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi was asked directly about the dates of these elections and the reasons for postponing them. The president responded with an admission, for the first time, that the local elections had been set to occur in 2017, but they had to be postponed because Parliament faced challenges issuing a large number of high-priority laws to bring the legislative framework in line with the new Constitution in all areas.[12] Then, during the Ask the President Conference held last July, he expressed his hope that the local councils law would be completed during the remainder of 2018 so that the elections could be held at the beginning of 2019.[13] However, a close look at Parliament’s performance during the last two years reveals that it was not always engaged with critical or urgent topics. On the contrary, it debated and adopted a number of laws that need not have been adopted or could have at least been postponed.[14] Hence, there must be other reasons for postponing these elections besides those the president discussed.

The state has taken a measure that reflects an attempt to substitute the MPs for the members of the local councils. Namely, it sought to have them convene monthly meetings with the governors and the governorate members to discuss the governorates’ requests until the local elections occur.[15] This underscores the idea of the “services MP” that has taken root in the mentality of both the Egyptian voters and the MPs. This idea renders the MP responsible for solving the problems pertaining to the electoral district that elected them and acting as an intermediary with the executive authorities, which affects the MP’s true role in oversight and legislation.

It is likely that the main reason for the postponement of the local council elections is the current regime’s fear that the Muslim Brotherhood’s enormous organizational capacity, especially in the villages, rural governorates, and Upper Egypt, will allow a number of its representatives to prevail in those elections despite the crackdown on the organization. Local elections are characterized by the large number (thousands) of candidates and victors, and it is difficult to ensure that they are all loyal to the current regime in the absence of an organized ruling party like the National Democratic Party of yesteryear. This issue came to light via the publication of excerpts of a security report discussing the state and security agencies’ fear that the Muslim Brotherhood would infiltrate these councils and contending that this would obstruct development.[16]

The Local Councils as a Gateway to Decentralization

The term “decentralization” as a system of administration appeared for the first time in amendments introduced to a number of articles of the 1971 Constitution in 2007.[17] The amended Constitution stipulated that, “The law shall ensure support of decentralization”. In this context, “the law” meant the local administration law.[18] However, as usual, the legislators did not intervene to amend any of the law’s texts to effectuate this constitutional article. Hence, this article remained merely a verbal amendment without tangible effects. The government at the time took no steps to support or effectuate decentralization as a system of administration. The 2014 Constitution then adopted administrative decentralization more clearly, stipulating that “the State shall ensure support of administrative, fiscal, and economic decentralization” and that a clear timeline must be set for transferring powers and budgets to the local administration units,[19] which must have independent budgets.[20] The new Constitution also clarified the local councils’ competencies, which revolve around monitoring the various activities within the administrative units and exercising instruments of oversight over the executive organs, from presenting proposals, briefing requests, interpellations, and other motions, to withdrawing confidence from the heads of the local units.[21]

These provisions are good overall if they are followed by a law clearly adopting decentralization and turning those outlines drawn by the Constitution into the beginnings of an administrative renaissance in Egypt. Decentralization is fundamentally a process of reforming the structure of the state system. Hence, its application must stem from a desire by the existing regime to introduce a real amendment to its policy and its fiscal and administrative system, not just from constitutional or legal texts. This approach has been adopted by many countries, particularly those in Europe, which found decentralization to be the ideal solution for raising government efficiency, especially with regard to administering public utilities and providing citizens with direct services such as education and health.[22]

Hence, proper application of decentralization achieves a number of results, the most important being that the burden of providing and monitoring the quality of utilities and services is lifted off the state’s central institutions and assumed by the administrative unit, be it the municipality or the village. Thus, the various ministries and [central] bodies need not intervene to solve every technical and administrative problem in each region. A true implementation of decentralization therefore requires finding a kind of “division of labor” between the central administration (represented by the ministries and the main governmental departments) and the local administration units at their various levels.[23]

Additionally, the local units are the most capable of effectively and efficiently administering their affairs as the head of the neighborhood or village is the most familiar with the problems facing their community and therefore the most competent to solve them. Implementing fiscal decentralization also leads to a better distribution of resources as government spending will go toward satisfying the real needs of the populace of each region.[24] For example, the state may develop and execute a national plan to build one thousand schools in Upper Egypt while a given region needs a hospital and not a school. This model also enhances the participation of citizens in decision-making, as well as their direct oversight of the people administering their day-to-day affairs.

Conclusion

The Egyptian state is characterized by extreme centralization. Despite the adoption of the system of municipal and local councils since the late 19th century, the decision-making circles long emanated from the central administration in all its forms. This makes reaching decentralization extremely difficult, especially amidst the rampant bureaucracy and corruption within the state’s administrative structure. The matter also requires convincing citizens of the importance of the local administration units and elected councils. Above all, questions must be asked about the doubtful extent to which the ruling regime desires to implement them. To this day, the position of governor is always held by (male) military or police figures as the government sees this is the best way to keep control.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Egypt, Constitutional reform, decentralization, local councils

[1] Article 242 of the Constitution states, “The existing local administration system shall remain in effect until the system stipulated in the Constitution is gradually implemented within five years of the date it enters into effect, and without prejudice to Article 180 of this Constitution”.

[2] “Ilqa’ al-Qabd ‘ala Ra’is ‘Hizb Misr al-Qawiyya’ ‘Abd al-Mun’im Abu al-Futuh”, RT Online, 14 February, 2018.

[3] “Fatwa min Maljis al-Dawla bi-‘Adam Mashru’iyyat Jami’ al-Kiyanat al-‘Amaliyya al-Mustaqilla”, Shorouk News website, 9 December, 2016.

[4] “3 A’da’ min Majlis Niqabat al-Attiba’ Yu’linuna Istiqalatahum bi-Sabab ‘al-Tasallut wa-l-Fardiyya”, Youm7 website, 13 May, 2018.

[5] See Menna Omar, “Mashru’ Qanun al-Jam’iyyat, Nahwa al-Qada’ ‘ala al-Mujtama’ al-Madaniyy al-Misriyy? ”, The Legal Agenda website, 28 November, 2016.

[6] Local administration is a system that rests primarily on decentralization as a means of organization and administration based on distributing powers and competencies between the central authority and other, legally independent bodies. See the paper “Nizam al-Idara al-Mahalliyya” issued by the First Arab Forum for Local Administration Systems in the Arab World, August 2003.

[7] Egyptian System Law of 1883, issued on 1 May, 1883.

[8] Articles 132 and 133 of the 1923 Constitution stipulated that the local councils (municipalities-directorates) be formed via election. The Constitution also granted the councils competencies related to implementing public policy locally, obliged them to publish their budgets, and stipulated that their sessions should be open to the citizens.

[9] See Article 2 of Law no. 43 of 1979.

[10] The National Democratic Party ruled Egypt for approximately 40 years. Its rule ended with the outbreak of the revolution of 25 January, 2011.

[11] “Nanshur al-Nuskha al-Niha’iyya li-Masru’ al-Idara al-Mahalliyya”, Youm7 website, 30 April, 2017.

[12] “al-Ra’is al-Sisi: Kana min al-Muftarad Ijra’ Intikhabat al-Mahalliyyat al-‘Amm al-Madi”, ON Live on YouTube, 16 May, 2018.

[13] “Sada al-Balad | al-Sisi: Atamanna Ijra’ Intikhabat al-Mahalliyyat Bidayat al-‘Amm al-Muqbil”, Qanat Sada al-Balad on YouTube, 29 July , 2018.

[14] During the last two years, Parliament has been preoccupied with adopting the laws that impose more control and restriction on various areas, such as the media, the press, and creative freedom, and impose more surveillance on internet users and communications. At the same time, it adopted a number of laws that are totally unimportant at the current time, such as the law granting special treatment to senior leaders of the Armed Forces.

[15] “Masadir: Ittijah li-Qiyam al-Barlaman bi-Dawr Akbar ma’a al-Muhafizin wa-‘Aqd Jalasat Shariyya li-Munaqashat Matalib al-Muhafazat”, Youm7 website, 31 March, 2016.

[16] “Mufaja’a.. Ta’jil Intikhabat al-Mahalliyyat li-Ajal Ghayr Musamma.. wa-Taqrir Amniyy Yufaddil ‘Adam Ijra’iha qabla 2018 Khashyatan Tasallul al-Ikhwan”, Youm7 website, 31 March, 2018.

[17] After the amendment, Article 161 of the 1971 Constitution stipulated, “The Arab Republic of Egypt shall be divided into administrative units with legal personalities, among them the governorates, cities, and villages. Other administrative units with legal personalities may be established if public interest requires. The law shall ensure support of decentralization and regulate the means of enabling the administrative units to provide local utilities and services”.

[18] Law no. 43 of 1979.

[19] See Article 176 of the 2014 Constitution.

[20] See Article 177 of the 2014 Constitution.

[21] See Article 180 of the 2014 Constitution.

[22] “al-Muqarana bayna Namudhajayn Mutamathilayn li-l-Idara al-Mahalliyya: Hal Yumkin an Takun al-Lamarkaziyya fi Faransa Masdar Ilham li-Misr?”, Tadamun’s website.

[23] “al-Mahalliyyat fi Misr: Kayf Yumkin an Tuhaqqiq al-Lamarkaziyya Rafahiyya Akthar li-l-Muwatin?”, Arab Forum for Alternatives, Manshurat Qanuniyya website, 16 January, 2013, p. 5.

[24] Ibid., p. 6.