Lebanon’s Face-Changing Opera

The elite sectarian leaders [zuama] emerged from the 1975-1990 civil war surrounded by an aura that ensured their leadership would continue. Even those sidelined for not going along with Syrian tutelage returned 15 years later to play their leadership roles. There was no effort to bring about accountability for the past or uncover its atrocities. Rather, the prevailing system strived to suppress anything connected to the past via a policy of erasing memory, namely the memory of the war and its tragedies. This erasure involved, in particular, concealing the fates of the people who went missing during the war and the mass graves. Subsequently, the memory of heroes – along with the regime of elite leaders – prevailed, while the memory of the victims faded after the regime deemed it a grave threat to civil peace. Even the issues of the displaced and the war-disabled were ultimately reduced to a matter of financial compensation after every cent was exploited to strengthen the system of clientelism and elite leadership.

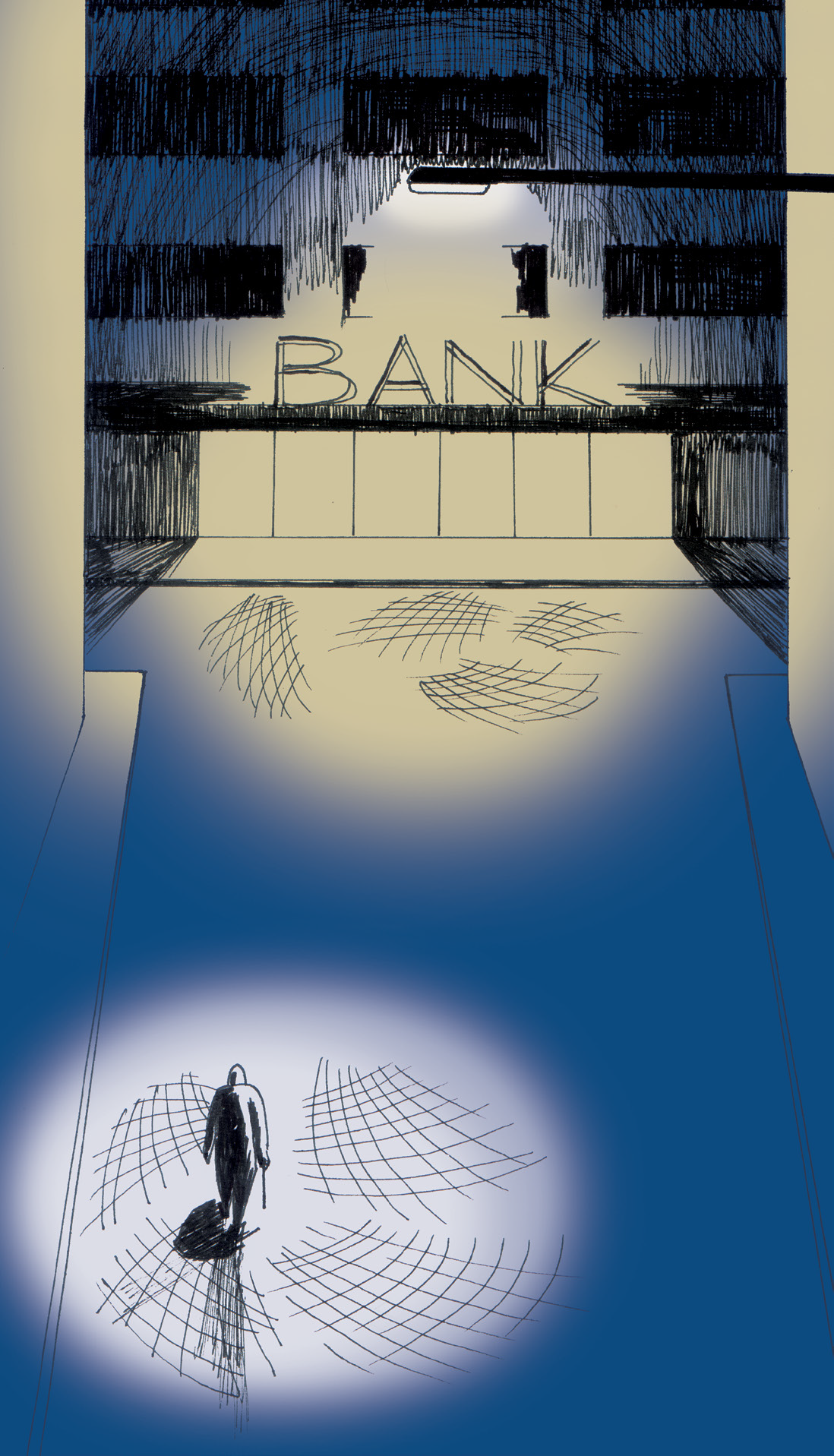

October 17 and the spectacular financial and economic collapse and bankruptcy of the state and banks, along with the possibility that most Lebanese people could lose their savings and deposits and become impoverished, was a turning point in this regard. The ugliness that the ruling clique of “warlords” had for decades managed to conceal behind various masks has finally become glaringly apparent now that the last mask has been removed – just like in a Chinese face-changing opera.

This opera includes three major scenes:

Scene 1: The Violation of the Private via the Violation of the Public

Except for rare moments, most importantly the 2015 garbage crisis, public wealth issues, including communal and public property and public utilities, have remained on the margins of public discourse over the last three decades. The decline of interest in “the public” has several causes, including sectarian partisanship, a weak sense of national belonging, a decline of trust in the state, and the baggage that the civil war’s atrocity and destruction left with many citizens, which manifested itself in introversion and withdrawal into private space and relative indifference to anything that occurs outside it. However, the strongest justification was that the general public conceded, consciously or subconsciously, that civil peace requires appeasing the sectarian leaders and therefore resignation to a certain degree of corruption and public property theft. Of course, this resignation was underpinned by acclimatization to a reality that seemed unchangeable to many people.

Consequently, the encroachments on seaside and riverside public property were able to continue for decades after the 15-year war ended without the encroachers paying a cent to the state. Likewise, 12 years without a state budget or closure of accounts could pass amid total indifference, not to mention the financial engineering and the many other scandals that were kept absent or subdued in public discourse or ended in a blame game in which citizens become confused and the scandal subsides without identifying a clear culprit. We even became acclimatized to the collapse of the public school, national university, and public hospital, to dual electricity and water bills [one paid to the state and the other to private parties that fill the gaps in the state’s provision of these services], to the blasting of the mountains, to the killing of the rivers, to the designation of seashores [for private commercial use], and so forth.

Of course, this acclimatization would not have occurred so smoothly were it not for enticements that convinced citizens that their introversion within their private space was appropriate. These enticements primarily involved establishing citizens’ almost total freedom to do as they pleased within this space. One of the best examples is the consolidation of citizens’ rights to exploit their property – e.g. the increase of property exploitation ratios [which determine what portion of a property can be used for construction] – in conjunction with the erosion of the controls imposed. Some of these controls are required by a minimum level of social regulation, such as those concerning proper administration of sewerage networks and environmental conservation. This all occurred via the amendment of laws or simply the nonapplication of existing laws. Hence, erecting buildings without a license or in contravention of licenses became a common practice sanctioned by the public authorities on the pretext of enabling citizens to exploit their sacred property. This trend culminated in 2019 in the adoption of a law settling construction violations that occurred over five decades (1971-2019). Another example is banking secrecy, which guaranteed depositors’ privacy and insulated them from any prosecution.

Hence, there seemed to be an implicit agreement accepting the leaders’ theft of what is public in exchange for liberating private property from any controls limiting its use or exploitation and, in practice, for making it akin to private emirates.

The October 17 shock should be understood as the moment not when the political authority’s corruption was exposed (it was already exposed and well known) but when the people sensed that the corruption had transcended the public sphere, public property, and public funds and invaded their private sphere, just as occurred in summer 2015 when the corruption in waste management – which the people knew all about already – invaded their noses and the balconies of their homes. This invasion occurred gradually and in several forms: the encroachment on their livelihood and their mobility in a country lacking public transport when the wheat and petrol importation crisis began; the encroachment on WhatsApp, which constitutes a distinctly private space for many youth; and perhaps most importantly, the encroachment on their incomes in Lebanese currency when its value – along with their deposits and savings – collapsed because of the banks’ insolvency. Gradually, depositors realized that the banks that they had entrusted with their private money were actually a tool for drawing this money in and then converting it into public funds by depositing it in the central bank in exchange for high interest. They also realized that the greatest invasion of their privacy was therefore the squandering of their money in the same manner that all other public funds and property have been squandered, usually amidst public acceptance.

When the divides between the public and the private – along with the latter’s inviolability – disappeared, it became very apparent that the discourse that usually sought to sanctify private property actually aimed to blind people to the encroachment on public wealth or convince them of its merit. If this discourse succeeded in doing so, encroachment on private wealth, after its conversion into public funds via the marriage between the banks and the central bank, would become easier. It therefore became clear that the “private” and the “public” are bound together and that abandoning the public would sooner or later cause the private to become fair game. This explains the prominence of accountability for corruption and recovering stolen funds at the forefront of the revolution’s demands.

Scene 2: The Citizen’s Vulnerability and the Banks’ Best Interest

Scene 2 is the exposure of citizens’ vulnerability before the banks. When the banks stopped paying their debts to depositors, the central bank took no step to seize them. It thereby allowed the banks to snatch away depositors’ rights and, in practice, commit the ultimate collective violation, with the victims numbering hundreds of thousands.

While the depositors initially managed to obtain a number of judgments supporting them,[1] the Court of Cassation (i.e. the supreme court),[2] along with several hidden hands, quickly closed this avenue. The biggest scandal in this regard occurred in the office of Cassation Public Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat, the head of the apparatus that the law vests with defending the public rights of society.[3] Instead of doing so and thereby protecting hundreds of thousands of depositors, Oueidat turned the investigation into the banks into a cordial meeting with them. This meeting concluded with the establishment of rules regulating the relationship between the banks and the depositors, rules that in practice were the cover that the banks had for months been looking for in order to shirk their legal obligations toward depositors.

This bias was also reflected in a series of behaviors by the Ministry of Interior, which assigned personnel to protect bank branches from protesting depositors and stringently pursued them. It also appeared on the level of legislation via the successive “capital control bill” drafts, which are merely another cover for the bank’s arbitrariness.[4]

Facing this scene, people realized that resigning to the leaders’ control over the judiciary and public administrations had paved the way for the law of power and the destruction of the principle of equality before the law. This realization manifested itself in widespread cursing of the leaders in a manner akin to smashing idols, as well as the incorporation of judicial independence into the revolution’s priorities.

Scene 3: The System Builds an Economy in Its Own Image

Finally, it has become clear to everyone that the current financial and economic crisis is organically tied to the political system, which bears primary responsibility for it. The system’s responsibility stems not only from its failure to manage the economy or anticipate the crisis’ consequences but also – and in particular – from its creation of an economic model in its own image, a model that combines a rentier economy with neoliberal tendencies. Just as political power is concentrated in the hands of a select few who managed to divide the “ruled” into frameworks subordinate to them and their leadership, so too are capital and opportunities for employment and production, which ensures that these same frameworks persist and prevents any escape from them.

The best evidence of this is the banks’ absorption of most capital (including that belonging to expatriates) by offering high interest on a wide scale and the replacement of production with importation once the value of deposits approached three times the value of domestic production. Furthermore, the economic activity remaining in the areas of commerce, services, and real estate succumbed to the logic of monopolies and networks of interests, all in parallel with the attack on labor unions and constriction of workers’ rights. With the concentration of political power and financial power in the hands of a few, the virtually inevitable marriage of the two – albeit via bargaining – ensured that rule from above continued. Naturally, this caused manifestations of democracy, along with manifestations of both a competitive economy and social justice, to disappear gradually.

Hence, it has become clear that the process of transitioning to a democratic system necessarily requires restructuring the economy to make it a democratic, productive economy free of monopolies and based on social justice. This also explains the prominence of constructing a productive economy at the top of the revolution’s demands amidst the combined slogans “all of them means all of them” and “down with bank rule”.

These are some of the main scenes of Lebanon’s face-changing opera and the lessons derived from them. So let’s keep watching…

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Lebanon, Corruption, Public property, Banks, Economic Crisis

[1] Nizar Saghieh, “Ab’ad min al-Tiqniyya al-Qanuniyya fi Qadaya al-Capital Control, aw Hina Yusbihu al-Hukm Manbaran li-l-Tandid bi-Ta’assuf al-Masarif wa La-Mubala al-Hakim”, The Legal Agenda, 27 January 2020.

[2] This was evident in the Court of Cassation decision issued on 26 February 2020, which deemed that compelling the bank to execute international transfers involved a serious dispute that the summary affairs judiciary could not resolve.

[3] Nizar Saghieh & Imad al-Sayigh, “al-Niyaba al-‘Amma al-Tamyiziyya Tandawi tahta Rayat al-Masarif: Taqyid Huquq al-Mudi’in bi-Hujjat Himayatihim”, The Legal Agenda, 14 March 2020.

[4] The Legal Agenda’s statement on the draft banking controls bill: “Dawabit Mu’aqqata min dun Ghad”, The Legal Agenda, 13 March 2020.