Lebanon’s Experimental Judicial Reforms: Trial or Error?

During 2013, the executive and legislative powers in Lebanon were suspended eight times. Executive powers was suspended following the government’s resignation in March 2013, and legislative ones following failure to attain quorum at the National Assembly (Parliament). The judiciary was also affected by these events. Judicial appointments of dozens of newly graduated judges from the Judicial Studies Institute (JSI) were placed on hold. During the same year, however, numerous initiatives regarding judicial organization, some experimental in nature, were taken at the level of the Ministry of Justice and the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC). They were flaunted as unprecedented reforms taken “for the first time in the history of the Lebanese Judiciary”.

Regardless of how befitting or beneficial these previously untried initiatives were, the judicial year in question could be called the “year of firsts”. The majority of the experimental initiatives were aimed at improving the judicial public service. Some were aimed at the assessment of judges and making accountability measures more efficient. Other tests strengthened the capabilities of public judicial institutions, but were not supported by any procedures enforcing the guarantees necessary for judicial independence. In fact, a number of said tests diminished or prejudiced the judiciary’s independence.

Judicial Organization

In the past year, experimental initiatives regarding judicial organization may be appraised in relation to three themes:

Evaluation and Accountability

Evaluating Judges and the Making of the Ideal Judge

The experimental initiative to evaluate judges commenced in 2012 in preparation for issuing judicial appointments. The Ministry of Justice, in coordination with the SJC, assigned one of the young judges to gather statistics on Lebanese courts in 2012 and again in 2013.

Less than a year after its launch, the ministry declared the initiative successful citing the increase in the courts’ productivity. The Ministry was especially proud of the remarkable progress achieved by the courts of Beirut. The number of decisions issued by the capital’s Courts of Appeal rose from 200 to 400, i.e., a 100% increase. Productivity also increased in other courts, although to a lesser degree. The minister thus appeared to be making a two-tiered evaluation: the first was an evaluation of individual judges for the second year in a row; the second was an assessment of the evaluation system itself by comparing the number of the courts’ judgments before and after the evaluation practice was put in place.[1]

Given said results, the minister concluded that “the output of any institution will improve and increase when there is accountability and a will for such an improvement”. The will referred to was that of the minister, and the accountability was the one he established with limited cooperation from the heads of judicial institutions.[2]

However, the evaluation system introduced by the minister is far from perfect. Judges had no role in setting it up and guarantees against abuse were not incorporated into the process. The evaluation takes place outside the institutionalized frameworks as stipulated in the Administration of Justice Act. More importantly, there is no reference to the Judicial Inspection Committee which, in principle, should be in charge of conducting evaluations and enforcing accountability.

In effect, the minister created parallel or alternative mechanisms to the established judicial institutions (an instance of “backstreet reforms”),[3] an unprecedented move in Lebanon. At best, these mechanisms will lead to short-lived results that are unlikely to outlast the minister’s end of term, leaving already dilapidated judicial institutions without enduring reforms. At worst, they will set a precedent for future justice ministers -who might be more politicized and less inclined for reform- to create their own set mechanisms in order to control judges.

Consequently, despite its importance, the policy of evaluation seems to be redrawing the boundaries between the executive power and the judiciary. The executive branch, represented by the justice minister, becomes the flagship of reform and takes credit for any increase in productivity. As a result, and instead of enforcing a system that protects judges from political pressure, political authorities themselves become the guarantors and enforcers of judicial efficiency – and they boast about it.

Notwithstanding the minister’s good intentions, and the seriousness and the necessity of evaluation mechanisms, the process is a continuation of an ongoing top-down approach to judicial reform. It is one that has left judges, namely low ranking ones, captive of whatever role is assigned to them. Their independence is thus compromised.

An even more worrisome aspect is the degree to which the initial aims of the evaluations were betrayed. Contrary to the declared intention in 2012, the process is now limited to quantitative evaluation. The success of judges is measured by the number of judgments issued per judge (an important factor of evaluation). Neither the quality of judgments, nor the judges’ independence, nor their capacity to improve judicial discretion is taken into account in the evaluation process.

Moreover, on a practical level, judges will be encouraged to speed up the pace of trials and avoid any procedure, investigation or thorough examination that may prolong the time of trial. “Assiduous” judges may feel that their efforts to produce novel juridical opinions, develop the interpretation of the law, or understand social phenomena will not be taken into account; or they might even have a negative impact on the evaluation of their productivity.

Hence, judges issuing high numbers of judgments –regardless of quality– are honored, while judges taking their time to issue judgments -in the interest of fairness for instance- are to a certain extent penalized.

Under this set up, the model judge is the one with a paucity of jurisprudence, scarcity of references and a diminishing knowledge of cultural and social contexts. This new set up will definitely affect defense rights, promote prejudice and ready-made judgments (stereotyping), rendering judicial justifications and logic extremely superficial. Complaints of delay in issuing judgments will decrease, but complaints of the judges’ unfairness or ignorance will increase.

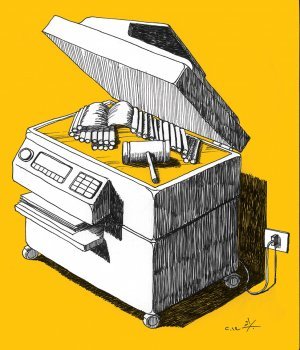

The judiciary will therefore appear as a “fast-delivery” type of public service stripped of all its functions of protecting citizens and their liberties, or developing laws and adapting them to new social needs. It is as if citizens resort to justice simply to expedite the acquisition of their rights, and not to seek justice before an independent power that is capable of fair adjudication in the face of powerful interests or parties.

The paradigm of productivity bore on the legislative work itself in a direct way, with the reduction of the judicial holiday period from two months to one. Meanwhile, no guarantees of the judiciary’s independence or mechanisms to increase productivity were introduced.

With productivity set as an embodiment of sought reform, a chilling specter emerges, that of the military court. The military court handles difficult questions requiring answers in the affirmative or the negative, without any justification, and issues a very high number of judgments on a daily basis. Fears of the impact the productivity policy will have on the military court are heightened, given that the media reports that it scored higher in terms of productivity than all penal and civil courts.[5]

Judges’ Dismissal by Disciplinary Decisions: Setting New Records

In 2012, the justice minister’s successful activation of the Disciplinary Council led to an adoption of the same approach in the following year. As a result, the number of judges dismissed reached a record high of three first instance judgments facing dismissal from service (two of which were ratified by the Higher Committee for Consultations at the Ministry of Justice and one revoked in 2013), and five temporary decisions of suspension from service. As for prosecution, no accurate statistics exist.

In terms of transparency, the Ministry of Justice issued illustrative reports on investigations or prosecutions in cases of judicial corruption, at the risk of possible disclosure of the identity of the judges in question. The report issued on June 3, 2013 is a case in point. It mentioned the referral of two judges to the Disciplinary Council based on the Judicial Inspection Committee’s recommendation and pointed to the justice minister’s decision to suspend one of the judges.

It is worth noting that some of these measures took place in the wake of news reports exposing the judiciary. Justice Minister Shakib Qortbawi’s abovementioned report dated June 3, 2013, came on the heels of the publication of a news article alleging the involvement of a number of judges and security officers protecting a drug ring.[5]

In fact, Qortbawi had a similar reaction in 2012 when he insisted on prosecuting the dismissed Judge Ghassan Rabah (then-member of Supreme Judicial Council and Chamber President of the Court of Cassation), following the release of an article on infractions attributed to Rabah.[6]

Qortbawi set a new norm by conceiving media reports on judicial errors and infractions as supplementing judicial inspection rather than an impermissible or decried act. Things could not be more different a few years prior. In July of 2008, the media became the object of derision following an episode of the talk-show al-fasad (meaning corruption), referring to a number of judges.[7] Qortbawi’s own stance on the subject was not always in sync with the new approach. On other occasions, he has expressed his opposition to the defamation of judges.[8]

The minister’s new approach is an important but insufficient one. The disciplinary action is often unsuitable given the gravity of the charges lobbied against the judge.

The most flagrant example was a decision by the High Disciplinary Committee headed by the SJC President himself. In June 2013, the president revoked the decision to dismiss a judge from service for his involvement in judicial brokering and and bribery. Instead, the president simply reduced his judicial grade by 4 grades.[9]

In other instances, judges involved in fraud and bribery were dismissed from service, however, they were granted their pension which could amount to USD$500 thousand. The disciplinary actions against the judges were not followed by any penal action.[10]

As the highest authority, in terms of disciplinary action, the SJCs decision suggests its willingness to retain such judges within the judiciary. This is despite the suspicion and discomfort such a decision might generate among lawyers and other stakeholders, who are unlikely to want to appear before such a judge.

More importantly perhaps, these disciplinary measures were not accompanied by others to promote the independence of judges or to investigate and prosecute the influential or wealthy people implicated in bribery or interference in the judicial process. As such, these people were given a free hand to continue with their practices.

First-time full extent accountability: Dismissal of a judge without trial

In November 2013, the accountability campaign reached a crescendo with the first-time application of article 95 of the law regulating judicial justice. The campaign was billed under the title “Judge resigns with the first application of Article 95 in judicial history”.[11]

Under the cited article, the SJC can discharge any judge based on the recommendation from the Judicial Inspection Committee, without trial or right to appeal if the decision is approved by 8 of its members. The judge in question reportedly resigned after he was summoned in this context, and his resignation was approved by Qortbawi.[12] Qortbawi confirmed this matter on Lebanese tv station OTV on October 16, 2013.

The application of Article 95 illustrated the gravity of what accountability could mean when applied without taking judicial independence into account. The process could become random, judges would lack the basic judicial guarantees, and they would become much more vulnerable to outside pressure. What is left of the judiciary’s immunity will be threatened under the cover of reform.

In a telling sign, the SJC set up its meeting with the resigned judge on October 10. Three days earlier, the largest movement by young judges demanding the creation of a judges association was announced. There is no confirmed link between the two incidents. However, one wonders whether Article 95 was used as a show of strength to remind judges of what the SJC can do in terms of repressing their movement.

The minister of justice, the SJC president and even the Lebanese president were very proud of the application of Article 95;[13] The Legal Agenda warned of the gravity of such a step and the negative impact it might have on judicial independence and on the legitimacy of the entire process of accountability.[14]

In sum, the experimental initiatives of evaluating judges have been primarily focused on measuring productivity in a quantitative manner, with no regard to the quality of judgments or to the independence of the judges’ work. In certain instances, such as the application of Article 95, this independence was even undermined. It is as if the reform was bent on enhancing judicial public service in terms of conflict resolution, with total disregard for the function of the judiciary as an [institutional] authority. The public fallout between the minister of justice and the SJC over judicial appointments is yet another indication regarding the nature of these announced reforms.

Judicial Appointments: Good Management Criteria for Public Service

In 2012, several announcements spoke of impending judicial appointments that finally took place in 2013. The selection of judges relied on criteria set by the SJC and approval by the minister of justice. This selection was based on the results of the aforementioned evaluation conducted for the first time. The appointments were initially delayed until the vacant positions of the SJC president and the public prosecutor were filled, but were later suspended due to ensuing tensions within the SJC.

The disagreement appeared to place Qortbawi’s desire to set “objective” criteria for appointments in confrontation with the SJC’s chronic practices of political favoritism and clientelism within the judiciary.[15] As a result, the initial draft for judicial appointments was dropped and a more restrictive one adopted. The latter was limited to filling the vacant positions and appointing JSI graduates, along with some minor amendments.

However, on February 28, 2013, public opinion was taken by surprise when Qortbawi announced in an official statement his decision to send back a revised draft to the SJC. The revised draft included “multiple detailed notes, considering that the project does not constitute a step towards judicial reform”, a reform that he [Qortbawi] was working towards since he held office.[16] Surely this disagreement is not the first of its kind. However, it is the first time that a minister of justice publicly discloses their disagreements with the SJC regarding appointments. The prevalent practice is for political forces to partake in wheeling and dealing for influence behind the scenes.

Qortbawi’s statement stood out for its harsh unequivocal language and its explicit reference to the reasons behind the disagreement (as perceived by the Ministry). The dispute, according to the statement, mainly revolved around the SJC’s disregard for objective criteria. These criteria include reward and punishment, as well as productivity and rotation when making judicial appointments, especially in the field of criminal justice.[17]

The public nature of the dispute confirms the randomness and selectiveness of judicial appointments which, in turn, further desecrate judicial practice. However, the criteria presented by Qortbawi, mainly revolving around conditions to enhance judicial public service (i.e., productivity and accountability), are unrelated to criteria that would ensure judicial independence. Top among such criteria would be the principle of seeking the consent of judges prior to their transfer from one post to another.[18]

In short, no party seems genuinely concerned with ensuring the judiciary’s independence. The issue of judicial independence was not addressed, the minister and the SJC failed to overcome their differences, and judicial appointments came to a complete halt,[19] which left dozens of JSI graduate judges without work. This brings back to memory what happened between 2005 and 2008 when the appointments of more than 100 judges were put on hold.

Consolidating Capacities of Judicial Institutions: Reform or Attempt to Curb Freedoms of Expression and Assembly?

In 2013, new experimental initiatives were introduced in an effort to strengthen the capacities of judicial institutions: A secretariat was assigned to the SJC. Advisory committees, including “representatives” of the different categories of judges, were assigned to assist heads of provinces. Although it is still early to judge the reform dimension of said two measures, the underlying approach still raises concerns. These measures might strengthen the capabilities of judicial institutions at the expense of the essential guarantees for the independence of judges, and especially at the expense of freedoms of expression and assembly, as I shall argue next.

SJC Secretariat: Media Office Speaking on Behalf of all Judges

In 2012, the Ministry of Justice submitted a draft decree for the establishment of an SJC secretariat. Although the draft was not yet presented to the Lebanese government, the SJC activated some of the functions stipulated in the draft decree. SJC chairman declared this move in an interview with the Judicial Magazine (Medjalla Kadaiyat) (Issue No. 11, October 2013), stating that the SJC secretariat was founded to serve as “the council’s administrative tool and support it in enforcing its decisions”.

The SJC secretariat includes the Central Administration for Statistics which is in charge of the aforementioned judges’ evaluation process. Another important function of the secretariat is the Media Office which cooperates with the media “in order to help maintain the truthfulness of judicial news while ensuring the privacy of the concerned”. The secretariat will manage a website for the SJC in order to enhance communication between the SJC and judges, and the SJC and Lebanese citizens. It will also pursue the computerization of the judiciary and follow up with donors regarding ongoing research in the judicial field.

The SJC had announced that the European Union allocated EUR€1 million for the council to work on promoting the rule of law and transparency in judicial work. The Media Office has so far issued a number of press releases including corrections of reported news and statements reflecting the body’s point of view. The SJC’s role does include the rectification of publicly released information, but there is a fear that the SJC, given its structure, might be employed to steer the official discourse of the judiciary, whether in defense of judges affiliated with the ruling clique or attacking those opposed to it.

The founding of the media office, in conjunction with the curtailment of the judges’ right to freedom of expression through reaffirming the code of silence under the obligation of reserve, is cause for concern. The SJCs circulars on judges’ conduct, namely the one issued on March 21, 2013 had reminded judges of the obligation to refrain from making any statements on any judiciary-related or public affairs-related case.

Advisory Committees on the Province Level: Judges Assemblies under Judicial Hierarchy

In 2013, another important attempt at reform was the SJC’s decision to establish advisory committees on the level of provinces to “assist the First President of the Court of Appeal in his administrative duties”.

In addition to the First President, the advisory committee includes five judges representing five role-based categories of judges (presidents of chambers of the Court of Appeal, auxiliary judges at the chambers of the Court of Appeal, presidents of chambers at the Court of First Instance, magistrates, investigating judges, Appeals Attorneys Generals and members of chambers at the Court of First Instance). Members of each category convene during the first week of the judicial year to nominate 3 judges from amongst its ranks. The First President of the Court of Appeal -with the SJC approval- chooses one of the candidates for membership in the advisory committee.

This initiative is significant on three levels. First, it is a test for judges of the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal in terms of practicing “the right to vote”, which might later help consolidate the principle of electing judicial officials by their peers, an important criterion for the judiciary’s independence.

Second, the initiative could be the basis for judicial activity within the framework of courts, by promoting interaction and communication between judges of the same court. This might become the pilot phase for founding judges’ associations or clubs. Such possibility is reinforced by an Article of the decision that stipulates the necessity for the advisory committee to meet with all judges of the province to present its agenda and get their feedback.

Third, despite the advisory nature of the committee’s role, the latter serves to expand the circle of those involved in the decision making process in courts, reducing the rule of hierarchy, which currently places all administrative powers in the hands of court presidents. Contrary to laws adopted by France and several states in the region like Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco, the law regulating the Lebanese judicial justice grants wide-ranging powers to court presidents without allowing for the formation of general assemblies for courts.

Upon close examination of this measure, one must question the actual possibility of reaping its supposed benefits under the current set up; whereby judges’ elections results are subject to screening by high-ranking judges. The latter would therefore be appointing the committee’s members regardless of the election’s results. The SJC has actually billed the advisory committees as an alternative to the judicial association demanded by judges.[20] Therefore, there is a risk that said committees might be utilized to deter judges from founding an association of their own and to question the legitimacy of such an initiative.

Under such circumstances, the culture of hierarchy will be reinforced and the entire electoral process will be seen as nothing more than a ploy to marginalize and co-opt judges, and give them the illusion of participation in the decision making process of judicial organization.

This is an edited translation from Arabic.

References:

[1] See Nizar Saghieh’s: Islah al-kada men khilal zyadat adad al-ahkam: al-kadi al-namouzaji fi dawe islahat, 2012-2013, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 11, dated October 2013.

[2] In the context of demands by presidents of Courts of Appeal for an authorization to be given to the judge in charge of conducting the evaluation, the SJC president reminded the presidents in a statement issued on July 18, 2013, that they can request evaluation results for their court ahead of its publication in the general report by emailing the judge in charge of the evaluation. This isn’t a guarantee in anyway, as long as there isn’t any third neutral party to appeal to, if evaluation results are contested.

[3] See Nizar Saghieh’s: al-nawaya al-hasana fi islah al-kada, ibid.

[4] See Saada Alwa’s: nuwwabuna aghla al-atilin an al-amal, Al-Safir, dated February 27, 2012.

[5] Al-Akhbar, dated June 30, 2013. Qudat wa dubbat yahmun shabakat mukhaddarat: ibn al-Nafith yaflut min al-’iqab.

[5] Al-Akhbar, dated November 27, 2013.

[6] Mohamed Nazzal, Al-Akhbar, dated February 16, 2012.

[7] See Nizar Saghieh’s: Mouhasabat al-kudat: khutuwat men doun ghad, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 9, July 2013.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid

[10] See Nizar Saghieh’s: kadiyat ghassan rabah wa hikayat al-mouhasaba al-da’iah: khoruj mohin mah’ habet mesek, published on the website of