Lebanon: Top Administrative Judges Sidestep Institutional Process

The regulation of entry into the judiciary constitutes a key factor in reforming the judiciary when the will to do so exists. The issue becomes even more pressing when there is an intent to expand the structure of the courts, as the legislators declared in 2000 with regard to the establishment of regional administrative courts.

However, the appointment of State Council (SC) judges in the past decades reveals several issues:

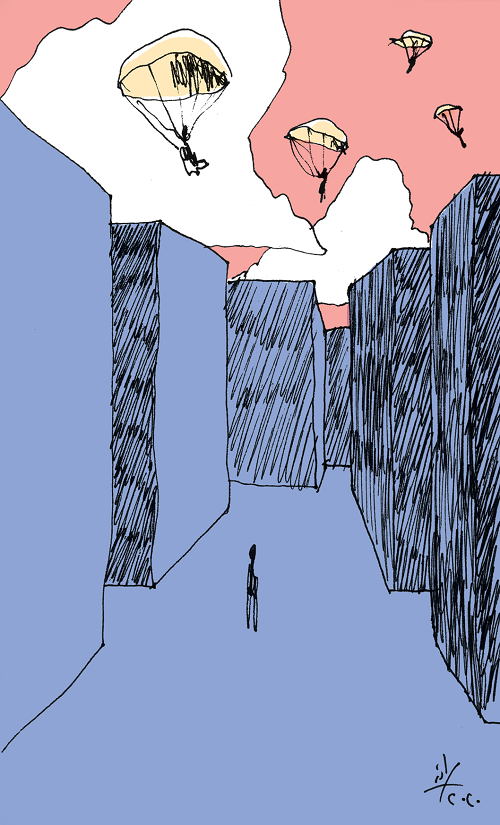

Firstly, there is duplicity in the avenues into the SC. While training in the Institute of Judicial Studies (IJS) is the primary avenue, the SC’s president and chamber and department presidents usually “parachute” in via decrees issued by the executive branch. While these figures usually come from the judicial judiciary, they generally have the largest effect on the SC’s performance because of the extensive powers they enjoy by heading the hierarchy within it. In addition to strengthening the political authority’s ability to influence the head of the SC, this means of appointment also frustrates the SC’s judges, whose hopes of assuming its high positions wane and vanish as they periodically witness judges – some without any experience in administrative law – drop down upon them.

Secondly, there are temporal gaps in the appointment of new judges. These gaps have not only exacerbated the vacancies in the SC’s cadre but also thwarted some of its fundamental reforms, most importantly the establishment of regional administrative courts.

Thirdly, although the judicial authorities stress that the IJS’s competitive entrance exams are impartial, their conditions raise questions, especially regarding their social impartiality. The role played by sectarian, gender, and familial considerations, particularly with regard to possible hereditary passing of judgeship, must also be examined.

Duplicate Avenues into the SC

The State Council Statute lists multiple means of appointing SC judges. However, the appointments over the past decades, especially the regular ones, reveal a tendency toward two means. The first and by far the most common is the appointment of people who pass the IJS’s entrance exams and complete their three-year training in the institute (59 judges from 1991 to 2020, liable to become 65 with the graduation of the latest batch in mid-2021). This means of appointment accounts for over 80% of SC appointments since 1991 and reaches 92% if we exclude appointments to top positions. The second means, which is restricted to appointments to top positions, is direct appointment without any exam and without passage through the IJS. These appointments are made from among judicial judges exclusively by governmental decrees. This means has been used to appoint all SC presidents for approximately 20 years (Ghaleb Ghanem in 2000, Shukri Sader in 2008, Henri Khoury in 2017, and Fadi Elias in 2019). It was also used to appoint the last two government commissioners in the SC, namely Abdul Latif al-Husseini (2010) and Feryal Dalloul (2017). Other judicial judges have been appointed chamber presidents, most recently Judge Antoine Baridi.

It can be said that a duplicity now governs the regular appointments in the SC: rank-and-file judges are selected via the competitive exam and groomed within its system via the IJS, whereas the top judges are judicial judges who were parachuted into their high positions via decrees issued by the government in order to grip the SC from above.

Corroborating this point, Ghaleb Ghanem’s appointment as SC president in 2000 was accompanied by an amendment to the State Council Statute to adapt the legal requirements for this position to his attributes. At the time, Ghanem was known for being close to MP Michel Murr, one of the key players in the appointment of Christian judges. As for Shukri Sader’s appointment to this position in 2008, it occurred under pressure from the March 14 Alliance to compensate and reward him for his efforts in establishing the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, the court for trying the murders of Prime Minister Rafic Hariri. The appointment happened at the last minute after one of the SC’s judges, Andre Sader, began receiving congratulations on his appointment. Judge Henry Khoury’s appointment differed from the previous two in that it did not fill a vacant position. Rather, it occurred after Sader was pushed to resign from the position in 2017. Here, too, the appointment occurred under pressure from the group surrounding President Michel Aoun. Then-minister of justice Salim Jreissati attributed the change at the top of the SC to “the [presidential] era’s desire to change the judicial approach”. At the time, the Legal Agenda responded with a quote from a lecture by late judge Naseeb Tarabay: “The ruler cannot bring his own judges in the same way that he brings his own ministers and advisors”.[1]

The other avenues into the SC have accounted for few appointments. The last appointments from among experienced people occurred in 1994 via an exceptional law and encompassed just four people. At the time, these appointments were justified on the basis of a shortage of SC judges.

The other neglected avenue is the appointment of people with PhDs. Only three judges have been appointed via this means (in 1998, 2001, and 2004). While the SC Bureau could once exempt such appointees from training in the IJS, in 2000 the legislature intervened to explicitly require them to complete this training, just like those who pass the IJS’s entrance exams. An aversion to this is understandable on the basis of concern about political interference imposing candidates without an exam, especially given the academic decline of the Lebanese University and relative ease of obtaining a PhD from this institutio. It, however, poses an obstacle to attracting academic capacities that could boost the SC’s work and jurisprudence. The SC Bureau could, of course, establish objective criteria known in advance to protect itself and ensure that this power is exercised positively, rather than refraining almost entirely from exercising it.

Making matters worse, there are no incentives for people with academic degrees to enter the SC. Two administrative judges told the Legal Agenda about the SC leaders’ general apprehension toward any academic distinction inside the SC, an apprehension reflected by their impatience toward “theorizing” in deliberations.

Whatever the reasons for neglecting this means of appointment may be, it exacerbates the flaws in the SC’s organization and performance. Most prominently:

- It renders the SC’s leaders the only authority for evaluating candidates’ qualifications and grooming them via training in the IJS. No academic degree offers any advantage – not even a non-decisive one – in this regard. This belittlement and denial of any academic superiority or distinction enhances the aura surrounding the SC’s leaders irrespective of their academic abilities. Subsequently, the only recognized distinction inside the SC becomes hierarchy and the positions its members occupy inside it. Consequently, competition among judges to acquire this distinction (appointment in these positions) increases, along with competition over the satisfaction of the political forces that take charge of these appointments (which negatively affects the SC’s performance and independence). Conversely, academic competition or efforts by judges to develop doctrines and thus the SC’s jurisprudence (positive competition) are seen as tedious, inappropriate theorizing or “tiresome philosophizing” [tafalsuf], as we say in colloquial Arabic.

- In practice, it keeps all doctrinal or academic theories out of the SC’s deliberations and decisions, thereby obstructing the development of administrative law in its entirety, especially as this law customarily relies primarily on the jurisprudence of administrative judges.

- It leads to the prioritization of pragmatic considerations over principles. Hence, in its decisions, the SC prefers to resolve the issues using grounds based on the facts or particularities of the case in question, thereby retaining the possibility of adopting whatever stance it sees fit in subsequent cases rather than being bound by a particular orientation.

- Finally, it weakens research on the SC’s decisions. This prevents the dissemination of knowledge and the exposure of the contradictions therein lest they reoccur, as well as the derivation and consolidation of general principles. This deficiency is reinforced by the years-long delay in the publication of SC decisions.

Nine Years Without Exams: Extensive Vacancies Disrupt the Establishment of Regional Courts

As previously explained, the ISJ’s entrance exam and graduating from the institute constitute the main gateway into the SC, accounting for over 80% of SC judges since 1990. Hence, exam cycles must be held regularly, not only to provide the SC with the human resources it needs to perform the functions vested in it but also to allow graduates of law universities who wish to take the exam to do so without having to wait many years after their graduation.

The dates of these cycles reveal a great defect in the SC system. The exams, which launched in 1985 and last occurred in 2018, have not been held regularly. Rather, over the past decades, gaps of 12 years (1986-1998) and nine years (2004-2013) have occurred without any exam. Making matters worse, the first gap occurred during the period following the civil war (though the SC Bureau resorted to appointing four people without an exam in 1994 on the basis of the shortage of SC judges), and the second occurred after the legislator expanded the SC’s cadre in preparation for the establishment of the regional administrative courts, as previously explained. Subsequently, SC President Shukri Sader did not hesitate to invoke the shortage of administrative judges due to the SC’s failure to conduct exams in order to justify his failure to establish these courts. Even worse, a bill was introduced to change the planned regional courts from chambers composed of three judges to departments composed of individual judges and thereby abandon one of the guarantees of a fair trial, though it did not move forward.

An Exam Lacking Impartiality?

This section will address the conditions of the competitive exam and, specifically, the extent to which it is fair and impartial. These conditions are important because the exam constitutes the broadest and most common gateway into the SC, as previously explained. In this regard, we shall merely draw attention to some concerning aspects that could negatively affect the exam’s impartiality:

- Applicants for the 2018 exam were asked to fill out a form (essentially a candidacy application) that contained two categories of information that are difficult to justify or connect to the requirements of the judicial function. Firstly, they were asked for private information, such as their private trips abroad and their reasons for traveling. Secondly, they were asked for excessive information about their family members, including the previous and current jobs of their parents, siblings, and spouses. We must question what benefit such information is expected to provide for accepting or rejecting candidatures. Moreover, it could be used as a tool for social discrimination among candidates.

- The SC Bureau can exclude many candidates from taking the written exam based on subjective – or at least opaque – criteria, and the excluded candidates have no way to contest this outcome. Recently, the percentage of candidates excluded in this manner witnessed an alarming increase that undermines the principle of equality in assuming the judicial function and opens the door widely for all forms of discrimination, especially social discrimination and classism. In 2018, the number of excluded candidates reached 90 of 153, i.e. approximately 59%.

This practice is even more problematic because of the mechanisms via which it occurs. Primarily, it follows oral interviews conducted by the SC Bureau. The interview involves general, linguistic, and personal questions and rarely addresses the law, as former SC president Shukri Sader told us in a 2015 interview: “They have to answer questions in the three languages. I ask them about their family, their study, their childhood, and their relatives”.

No less gravely, this selection process also occurs based on security reports that are attached to the candidates’ files. The candidates cannot view the reports and therefore cannot discuss their veracity. Sader told the Legal Agenda that he sends a request to General Security to verify the identity of each candidate: “We discovered that one of the candidates had a history of check fraud. Another was bribing General Security personnel to push domestic workers’ papers through. I select approximately 70 of these candidates to take the written exams. I select people with no suspicions of corruption surrounding them or their families”.

- Proficiency in either French or English is a precondition for taking the written exam. Candidates’ knowledge of one of these languages is tested again in the written exam as part of the general education subject, wherein a mark of 6 out of 20 results in failure irrespective of their marks in other subjects. While language proficiency is important, in the Lebanese situation and amidst the degradation of public schools, it constitutes another ingress for social discrimination in the exam. Language proficiency should perhaps be considered an advantage rather than a reason to reject candidates.

- Several ministers of justice, including former minister of justice Bahij Tabbara, have stressed that sectarian criteria in the IJS’s entrance exam were disregarded following the Taif Agreement and therefore have not existed since the first exam cycle involving administrative judges, which was held in 1998, i.e. after the agreement. According to Tabbara, “Appointment is subject to the results that the trainee judge achieves, irrespective of his sect or affiliations”.[2] Yet there is constant convergence in the numbers of people from each sect who pass, either within one exam cycle or across two consecutive cycles. For example, a total of both 23 Christians and 23 Muslims passed the 1998-2015 exam cycles. Similarly, after the latest batch graduates from the IJS in 2021, the breakdown of Muslims who have graduated since its first cycle will be 12 Sunnis, 12 Shia, and 4 Druze. Here, this fact is being mentioned without jumping to any conclusion.

- Several exam cycles have raised suspicion that priority is being given to children of judges and, in practice, that judgeship is being passed down hereditarily. Pass rates among such people have been high in comparison to the rates among other citizens. In the 2016 cycle, two thirds of candidates who were children of judges passed. Of the people who passed the exams for entry into the IJS’s administrative department, children of administrative judges constitute more than 9%, which is slightly lower than the percentage that children of judicial judges constitute among people who passed the IJS exam for entry into the judicial judiciary during the same period (11%). Once again, we are merely disseminating this fact without jumping to any conclusion.

On the other hand, regarding the gender distribution of judicial positions, there has been a positive increase in the number of women entering the IJS since the beginning of the century. While men dominated the various exam cycles up to 2003, the 2004 cycle was a significant turning point, with seven women passing versus one man. After the graduation of the latest batch from the IJS in 2021, the total number of [administrative] judges who have graduated will consist of 36 women versus 29 men.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Lebanon, State Council, Administrative judges, Judges, Appointment

[1] “Iqalat Ra’is Shura al-Dawla Khilafan li-Khitab al-Qism: ‘al-Hakim La Ya’ti bi-Qudatihi kama Ya’ti bi-Wuzara’ihi wa-Mustasharihi’”, The Legal Agenda, 8 August 2017.

[2] “Tabbara Yu’akkidu ‘ala Dawr al-Qada’: Mu’alajat al-Milaffat Bi-La Intiqa’iyya”, Annahar, 6 September 2003.