Lebanon: Civil Marriages Struck Down for the Sake of “Equality”

On 28 November 2021, the first remote civil marriage in Lebanon was contracted via a judge in Utah, US. The news quickly spread among Lebanese, especially after the couple appeared in a TV report. This type of marriage began gaining popularity in Lebanon as it does not require traveling, which has become difficult because of the economic collapse and the General Directorate of General Security measures that deny many Lebanese access to a passport.

Before long, several Lebanese couples who contracted their marriages remotely in Utah were surprised by a barrier to registering them in Lebanon: the Lebanese Consulate in Los Angeles failed to send their marriage paperwork to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, or the General Directorate of Personal Status (GDPS) – after receiving the paperwork from the ministry – refused to sign it so that it could be registered. When one of these couples consulted the GDPS citing a previously registered marriage, that marriage was deregistered on the pretext of the “equality principle”, according to the couple’s lawyer.

Couples whom the Legal Agenda contacted in Lebanon concur that the principle of equality isn’t respected to begin with, particularly when it comes to contracting marriages. “Where’s the equality when those who choose religious marriage are allowed to marry on Lebanese soil while those who choose civil marriage are not?” asks one wife. “Where is the equality when those who cannot afford to travel are barred from getting married remotely? Does the state only allow people with money to have civil marriage?”

So far, approximately 70 couples residing in or outside Lebanon have married remotely in Utah. Only a few have been registered. Some of those marriages were later deregistered by the GDPS. The other couples are still waiting for their marriage to be registered in Lebanon.

Two Deregistered Marriages: How Do We Register Our Children?

Last October, Kay was born. His Lebanese parents found themselves unable to register him in Lebanon because General Director of Personal Status Brigadier General Elias Khoury simply decided to deregister their civil marriage already in effect. In an interview with the Legal Agenda, Kay’s father Khalil Rizqallah recounts the details. After learning that Utah allows remote marriage under certain conditions, he and his wife took that route, becoming the first Lebanese couple to marry in Utah from Lebanese soil via Zoom on 18 November 2021.

After the ceremony, Rizqallah’s official papers were sent to the Lebanese Consulate in Los Angeles. The papers then proceeded through the legal route to the Lebanese embassy, then the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, then the Ministry of Interior and Civil Registry, where the marriage was officially registered in Lebanon. Last May, the couple received documentation that their marriage had been registered in Lebanon. However, in September, while the couple was in the US, they learned that the security forces had come to notify them of a decision to deregister their marriage and were informed by the mukhtar [a neighborhood personal status official] and the wife’s family that they were abroad.

Days after the marriage was deregistered, Rizqallah’s son was born. Currently, there is no way to register him in Lebanon: “If the decision to deregister the marriage isn’t canceled, my wife and I will have two options: we remarry either religiously in Lebanon or civilly in Cyprus. However, this raises another issue concerning the mechanisms for registering a child born before the date of marriage.”

What happened to Rizqallah also happened to Farid Yazbek. He and his wife are expecting a child whom they will be unable to register because their marriage was deregistered in Lebanon. In an interview with the Legal Agenda, Yazbek explains that last April, he contracted his civil marriage remotely in Utah. His papers went through the legal process, and he received a marriage certificate registered in Lebanon and a family registry document (listing all family members and their marital status) last month. However, less than a week later, the marriage was deregistered, and the authorities asked him to hand over the extract and then returned his wife to her family’s record.

Yazbek is astonished by what happened, especially as he only resorted to this type of marriage after confirming with the relevant sources that it is legal: “Before contracting the marriage this way, we called the Lebanese Consulate in Los Angeles and the ministries of foreign affairs and interior. Everyone we contacted told us the marriage is legal and registerable in Lebanon. The same night, we went to Turkey. If they hadn’t confirmed the legality of this step, we would have married in Turkey. Who is responsible?”

Ceasing Registration

In conjunction with deregistering these two marriages, the Ministry of Interior ceased registering marriages contracted remotely in Utah. The people whom the Legal Agenda met say they chose such marriages primarily because they could not obtain passports due to the movement-restricting measures that General Security imposed last February, or because the economic collapse has made traveling abroad to contract a civil marriage unaffordable.

Farah Fayyad, whose marriage has still not been registered, tells the Legal Agenda,

“I got married last June. My husband and I have a copy of the marriage contract from Utah. The papers were supposed to follow the legal route. When we felt that the process was taking unusually long, we consulted the Ministry of Interior and learned that it didn’t have our file. We contacted the consulate, which was supposed to have sent it to the Ministry of Interior, to ask for the file number. They responded that it had been rejected by the Ministry of Interior, and papers for online marriage from Utah were no longer accepted”.

Fayyad, who is two months pregnant, asks how Lebanon can refuse to register her marriage when she called the Lebanese Consulate in Los Angeles and was told that the marriage is legal and registerable in Lebanon. She says that she may be forced to travel abroad for civil marriage or to undertake religious marriage in Lebanon, especially so that she can register her son.

Fayyad says, “Who is responsible for what happened to me? I chose remote marriage because the General Security measures prevented me from obtaining a passport – my appointment on the platform is next month – and I asked the people concerned whether the step was legal before taking it”.

While Fayyad’s marriage certificate reached the Ministry of Interior and was rejected, Dima Radi’s certificate is still stuck at the embassy, which was supposed to send it to the ministry.

In an interview with the Legal Agenda, Radi says that she got married last October via Zoom in Utah after she and her partner were told by the Lebanese Consulate and people who had gone through the same experience that the marriage would be legal and registerable in Lebanon. She adds, “Everything was going correctly. The marriage certificate was sent to the consulate, then to the embassy, which was supposed to send it to the Ministry of Interior. But it got stuck there, until we fetched it”.

Nobody informed her that her papers were on hold and that the embassy had decided not to send papers for this type of marriage to the Ministry of Interior. Had she not followed up, she would still be waiting for the marriage to be registered.

As with Fayyad, the inability to obtain a passport was one of the reasons that Radi chose this type of marriage: “My husband didn’t have a passport. I called General Security and told them that I needed a passport to travel for marriage, and they were unresponsive”.

Undoubtedly, the GDPS’ decision to deem several marriages contracted remotely void and not register others caused harm to the children that were or will be born from these marriages. However, lawyer and researcher at the Legal Agenda Youmna Makhlouf says that under the “putative marriage” doctrine, these children are considered “legitimate” irrespective of the marriage’s validity so long as one spouse was well-intentioned, so they should be registered as such.

The Legal Pathway

Patrick Damianos, the lawyer of several couples whose marriages were deregistered or not registered, tells the Legal Agenda that the marriages contracted in Utah can be divided into three groups:

The first group comprises the marriages that went through the whole administrative process and were officially registered in Lebanon, only for the GDPS to deregister them later.

The second group comprises those marriages whose papers stalled at the Ministry of Interior. Their papers went through the administrative process, being sent to the Lebanese Consulate in Los Angeles, then to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs via a diplomatic bag, and then to the Ministry of Interior to be signed and referred for implementation. However, the Ministry of Interior refused to sign them.

The third group comprises the marriages whose papers the Lebanese Consulate received from Utah but did not send to the Ministry of Interior because of unofficial instructions from the latter, which sent several back.

Damianos adds that each group has a different legal pathway. In the case of the first group, Rizqallah filed a State Council case challenging the GDPS’ decision to deregister his marriage. He also resorted to the judicial judiciary.

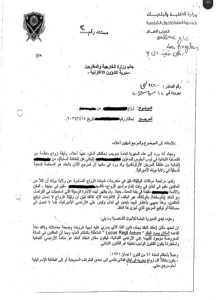

The GDPS’ decision to deregister Rizqallah’s marriage, which the Legal Agenda viewed, lists the grounds: the marriage contract does not bear the spouses’ signatures, the spouses do not reside on US soil, and the contract does not indicate the means used to communicate with the officiant when the contract was made.

The decision stated,

“Whereas the place where the contract is made is determined by the law of the country that applies to it with regard to its terms and the validity of its formalities [sic], pursuant to the public order principle of locus regit actum; Whereas as the contracting parties are present on Lebanese soil, the place where the contract was made is necessarily Lebanese soil, so Lebanese law must be applied… Whereas Article 61 of the law of 2 April 1951 stipulates that any marriage that a Lebanese person belonging to a Christian sect or the Israelite sect carries out in Lebanon before a civil authority is void… Whereas any agreement concerning marriage in Lebanon in which an authority residing outside Lebanese territory intervenes by any means has no validity in this realm and no legal effect”.

Before addressing the grounds that the GDPS listed for deregistering the marriage, Damianos points out that it exceeded its powers, which are limited to registration.

As for the grounds, he mentions that the US marriage certificate includes digital signatures in accordance with Utah law and that the Lebanese E-Transactions Law stipulates that such signatures have the same legal effects as signatures on paper.

Regarding the point about specifying the means whereby the marriage was contracted, he says that Lebanese marriage certificates drawn up in consulates or on Lebanese soil contain no field showing this means. Additionally, neither Utah law nor Lebanese law requires that this means be shown. Articles 26 and 29 of the Personal Status Registration Law merely stipulate that a marriage must be celebrated in the format followed in the foreign country where it is contracted.

He adds that in addition to the fact that the State of Utah acknowledged its jurisdiction over the marriage, the contracting parties have the right – pursuant to will theory – to choose the law to which they wish to subject their marriage, and they chose Utah law.

As for the locus regit actum principle (the place of the contract governs the act)(, Damianos asks how the GDPS’ general director managed to establish that the contracting parties were on Lebanese soil and whether he merely relied on their places of residence before marriage. Several couples who married in this manner were outside Lebanon, and the Ministry of Interior declined to sign their contracts too.

Concerning the second group, whose marriage contracts the Ministry of Interior refused to sign, Damianos explains that under Article 25 of Decision no. 60 LR of 1936 (Law Religious Sects), the GDPS is the registration authority, as mentioned earlier. In other words, it must “implement” – rather than scrutinize – the documents, as it previously did with a number of them (before deregistering some). Scrutinizing the documents falls under the power of the consulate that drew up the certificate.

Damianos says that when one couple objected to the GDPS’ non-implementation of their marriage certificate, the general director’s office refused to receive the objection. The objection was then directed to Minister of Interior Bassam Mawlawi, who referred it back to the general director. The latter rejected the substance of the objection, sticking to his decision not to register the marriage and mentioning that the directorate had deregisteredRizqallah’s marriage and returned his wife to her father’s record “pursuant to the principle of equality”. In other words, instead of registering the new marriage, the GDPS deregistered a registered one.

Thus for the second group, the legal grounds that the Ministry of Interior cited for not implementing registration are the same as the ones it cited in the letters deregistering marriages, so the legal response is the same.

Regarding the third group, whose papers the consulate never sent to the Ministry of Interior, Damianos says that they must wait for a decision to re-register the first group and register the second group before asking the consulate to send the documents to the ministry. The consulate refrains from sending the papers based on a request that appeared in the GDPS’ decision not to register one of the marriages: “We also hope that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates will instruct all delegations and consulates to take this issue into consideration when the marriage documents of parties residing on Lebanese soil are drawn up by an authority residing outside Lebanon”.

Damianos mentions that so far, the populace has not been notified that this type of marriage will not be registered: “To this day, such marriages continue to occur and the GDPS refrains from registering them without informing the people. They should at least announce the matter in order to spare people from material and moral losses”.

Regarding the GDPS’ power and the fact that it includes only registration, not examining the marriage’s validity or annulling it, Makhlouf cites an opinion issued by the Legislation and Consultation Committee in 2000. The opinion states, “Beyond the context of legal disputes, in which it is represented either by the civil registrar or by the Cases Authority in the Ministry of Justice, expressing a stance on the validity, invalidity, or nullity of a given marriage is outside the competence of [the GDPS], especially as this matter is extremely delicate and complicated”.

This opinion is based primarily on “the fact that the power of Personal Status Departments in relation to registering marriage and birth certificates is defined in the Law of 7 December 1951 on Registering Personal Status Documents”, as stated in its text. No part of this law “vests Personal Status Departments with the power to assess the validity, legality, or nullity of the marriage”, which is “part of the jurisdiction of the judiciary alone”.