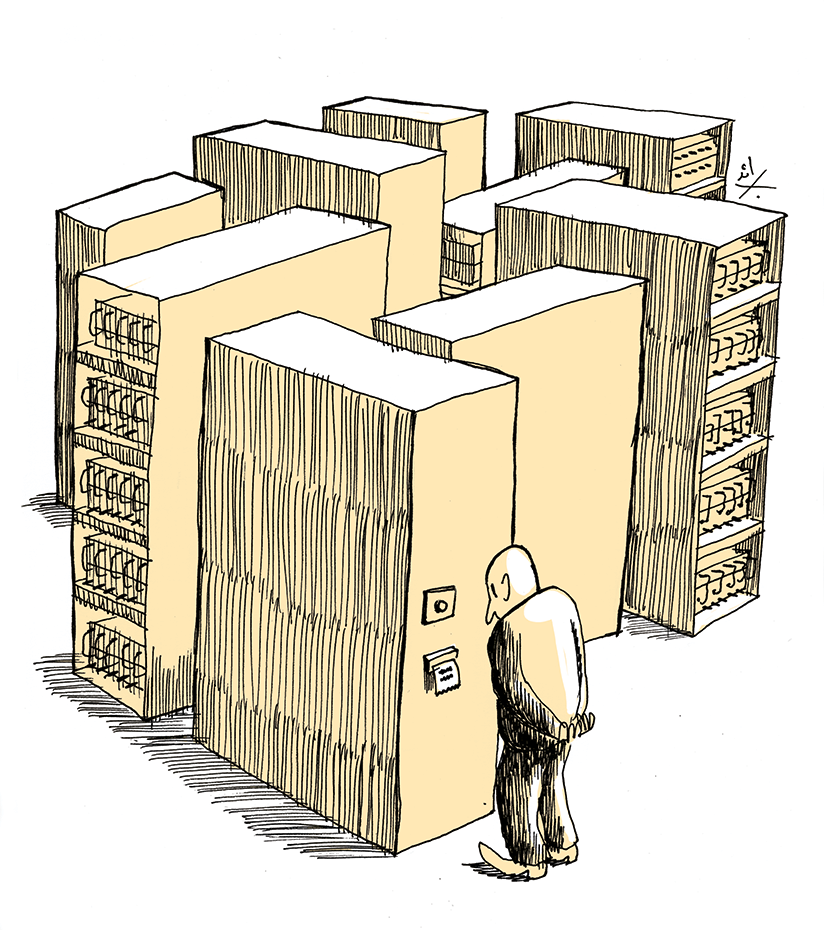

Lebanese Access to Information Law is for Boasting, Not Transparency

In late June 2019, The Legal Agenda received a letter from General Secretary of the Council of Ministers Mahmoud Makkieh stating that Makkieh refuses to comply with the information request The Legal Agenda, together with Kulluna Irada and a number of individuals, submitted to obtain information about the Council of Ministers decision concerning the Deir Ammar power plant. The request was refused not because of the information requested but because the Access to Information Law, according to Makkieh, is unimplementable as its applicatory decree has not been issued and the National Anti-Corruption Authority has not been formed.

Of course, this refusal by a public administration to comply with an information request is not the first of its kind, nor are such refusals limited to this administration. Rather, the administrations that violate this law almost outnumber those that faithfully implement it, as revealed by many reports by rights organizations, particularly the report published by the Gherbal Initiative in 2018. Nevertheless, a refusal in this manner by the highest of the executive branch’s administrations, which is supposed to lead by example, is akin to a coup against this law and instruction to all public administrations to refrain from applying it.

Hence, while The Legal Agenda and Kulluna Irada have challenged this decision before the State Council, its content and themes must also be refuted because of its gravity and what it suggests about the orientations of the political system as a whole.

Before proceeding, I must mention that the Access to Information Law was adopted in January 2017 as part of governmental efforts to adapt the Lebanese legal system to the UN Convention against Corruption, which Lebanon ratified in 2008. The law’s key virtue was that it paves the way for a radical change in the ability of individuals and NGOs to become informed about the public administrations’ work and, subsequently, the rules and controls that govern this work. The law aims to replace the secrecy that has prevailed and continues to prevail over the activity of these administrations with transparency. The government rushed to exploit the law in international forums as evidence of the development of Lebanon’s legislative system and the political authority’s engagement in administrative reform and combating corruption. The latest example of this boasting is the report the government issued on 14 December 2018 regarding the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. The report mentioned the law’s issuance more than five times to affirm Lebanon’s commitment to achieving administrative development, developing the liberal economic system, and combating corruption (items 12 and 14), and ensuring freedom of expression (item 90). In Item 14, the government even placed this law within a group of recent legislations aiming to apply the UN Convention against Corruption.

A Hypocritical System that Neutralizes the Law it Boasts About

The first conclusion that emerges from the decision by the General Secretariat of the Council of Ministers is the extent of the hypocrisy that drives the ruling authority in this area, which is the case for many laws that in recent years enshrined fundamental rights for citizens and were a theme of government boasting but never found their way into effect. The most notable include the Disability Rights Law, the Compulsory and Free Education Law, the Food Safety Law, and the Law on Establishing the National Human Rights Authority. This hypocrisy appeared not only in the letter’s orientation but also its content.

While the decision was replete with verbose praise for the law – it was described as “the ground-breaking law in enhancing transparency”, “the outstanding law that reflects an honest and resolute desire to increase transparency and root out corruption in the administration”, and “a qualitative shift in the way of interacting with the administration and in enhancing the level of transparency therein” – it was equally replete with flimsy arguments that, at their core, constitute a curtailment and distortion of the law’s content and that are all oriented toward making its entry into effect contingent on the issuance of applicatory decrees. Taking pride in the law’s significance, it seems, does not prevent the government from fabricating excuses to render it inoperative. The best evidence of this is the decision’s admission of the “triviality” [sakhafa] of some of these arguments, as I shall explain below.

A close examination of Article 25 of the law shows that, contrary to what the decision stated, it does not make the law’s effect contingent on the issuance of an applicatory decree whatsoever. Rather, it allows the government to issue applicatory decrees only “when necessary”. The article thereby repeats a phrase that has come to appear in virtually all important and large laws, giving the government the ability to facilitate the law’s implementation by issuing decrees whenever it deems necessary. This was affirmed by the Legislation and Consultation Committee in two separate consultations in 2017 and 2018, which stated that “the provisions of the Access to Information Law are applicable in and of themselves without recourse to particular applicatory texts issued by the executive branch, since the presence of matters that require the issuance of decrees has not become evident” (Consultation 441 of 2017 and Consultation 951 of 2018). It was also affirmed by the ruling the State Council issued on 13 December 2017 regarding the effect of disabled people’s right to work in the private sector. In that case, the Ministry of Labor, too, argued 15 years after the Disability Rights Law was issued that it may not be applied in the absence of an applicatory decree. The State Council rejected this argument on the basis that Article 100 of that law stipulated that the details of the law’s application could, when necessary, be determined via a decree adopted in the Council of Ministers. In other words, this provision is only relevant to the texts “whose application requires the issuance of such a decree, as evidenced by the use of the phrase ‘when necessary’”, according to the State Council.

Another distortion of the Access to Information Law found in the letter was the misreading of Article 18. After the letter mentioned that the article places the cost of photocopying the information on the requester, it concluded that the fact that this fee has not been set is “enough to prevent compliance with any request and, subsequently, to neutralize the law in its entirety”. The distortion is clear upon reading this article, which states that accessing documents is free at their physical location, as is receiving them via email, and that in the case of photocopying the requester cannot be charged more than the cost of photocopying. In other words, the administration has no margin for setting the fee, neither above nor below cost. Whatever the case may be, the fact that the fee has not been set poses no serious obstacle to the law’s implementation. Finally, the General Secretariat had no qualms, at the end of its analysis based on a misreading, about acknowledging the absurdity of the conclusions it reached. The letter stated, “the fact that the fee the requester must pay has not been set is enough, despite its triviality, to prevent compliance with any request and, subsequently, to neutralize the law in its entirety”. This statement reveals the heights that the government’s hypocrisy has reached as it shows that the government can order that an extremely important law that it boasted about in all international forums is inoperative on account of an argument that is not only obviously false but also trivial by its own admission.

The third, equally flimsy argument is that the law is contingent on the formation of the National Anti-Corruption Authority, which the law gives the power to examine the validity of refusals to give information by the public administrations. Remarkably, the decision deemed the authority’s existence a precondition for implementing the law based on its aforementioned power and on its power to propose applicatory decrees to implement the law and provide opinions on them. This argument also stands up to no serious debate because the authority’s power to examine the validity of a refusal is not exclusive, because the public administration must in any case abide by the law pursuant to its legal and ethical responsibilities even in the absence of an authority (i.e. a stick) that effects accountability for deviations from the law, and the issuance of an applicatory decree is under no circumstances a condition for applying the law, as I explained at length above.

Adding to the gravity of this decision is the fact that these arguments have emerged more than two and a half years after the law was issued and after a series of official statements emphasizing that the law is in effect. For example, the government declared in its aforementioned report issued on 14 December 2018 that it had established a website dedicated to the right to access information (www.accesstoinfformation.com), where the administrations’ annual reports, bills, circulars, decisions, and explanations of administrative decisions can be viewed. Setting up the site was billed as part of “a project to strengthen human resources management in the Lebanese public sector, under a good governance programme funded by the European Union”. Unsurprisingly, no such webpage is available at the aforementioned link. So why the change of heart? And what allowed the General Secretariat of the Council of Ministers to decide suddenly that this law cannot be put into effect?

Moreover, assuming that the 2017 law cannot be applied, what about the state’s obligation to respect the right to access information based on Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which is considered an inseparable part of the Constitution? What about the state’s obligation to encourage individuals and non-governmental groups to participate in efforts to combat corruption under Article 13 of the UN Convention against Corruption, which Lebanon ratified in 2008? What about the state’s interest in involving everyone in this effort, whose importance the letter acknowledged? If we accept, for the sake of argument, that the law cannot be applied for technical reasons, disregard all these texts, and deem that the administration is not compelled to give the information and therefore has absolute discretion to comply or not comply with these requests, then do “administrative ethics” (which the letter mentions elsewhere and to which I shall return below) not require that this discretion be exercised in a manner concordant with the legislator’s stated objectives in the 2017 law, with Lebanon’s international obligations, and with state interest? Or do all these robust considerations have no weight, per Makkieh’s assessment, versus a false argument that is “trivial” by his own admission?

A System That Uses Its Internal Disputes as a Pretext for Breaking Reform Promises

The second conclusion we can draw from the letter is the trend prevailing within the corridors of government of explaining any negligence to enact or implement laws via the disagreement between the forces participating in government. The goal is not just to cast responsibility onto the other political forces (which usually occurs). Rather, it is also – and most importantly – to shift responsibility for the negligence from the government or the political forces participating in it to a structural deficiency at the roots of the political and social system, namely the consensus system that prevents any decision from being adopted if there is no consensus on it among the political forces. It thereby becomes possible to perpetuate the obstacles to applying one law or another without anyone being able to charge any one of the political forces with responsibility for neutralizing it.

This can be discerned clearly from the space the letter allocated to criticizing the draft applicatory decree proposed by the Ministry of Justice to implement the Access to Information Law even though this matter has nothing whatsoever to do with the request the letter was refusing. While this criticism ostensibly aims to cast responsibility for the negligence onto the Ministry of Justice or the political faction that minister represents, its practical effect is to enable all factions to invoke the disagreement over the draft decree’s content to shirk the political responsibility that arises from delaying its issuance and, at the same time, to perpetuate the argument for not implementing the law until this dispute is resolved.

From this angle, the letter serves as an example of the performance of the political forces, which usually succeed in avoiding any mentionable political cost when reforms fail.

A System That Detests Transparency and Accountability

Finally, given all the above, it is evident that the letter reflects an apprehension towards transparency and the involvement of individuals and NGOs in monitoring the administration’s work and an attachment to the protocol of secrecy in administrative work. This becomes clearer when we consider the information that the letter refused to hand over, namely the Council of Ministers decision concerning the Deir Ammar power plant and the documents accompanying it. Many rumors about the legality of this decision and about persons close to several political actors benefiting from it have circulated.

Remarkably, the letter dedicated its final section to discussing “administrative ethics” (a concept taken from French scholar Maurice Hauriou, as evidenced by the letter’s use of the French version of the term). It concluded that the administration must give information exclusively to those who establish that they have a direct interest out of regard for their rights, while it appeared to consider intrusion by whosoever has no interest a hindrance to the administration’s work because of the burdens it imposes on the administration. Irrespective of this interpretation’s validity (it is incorrect as administrative ethics require the administration to exercise any discretion in the manner most concordant with public interest, which would be to effectuate transparency), in this regard the letter manifests one of the most prominent tendencies of the Lebanese administration (as well as some State Council judges), especially when it comes to disputes brought against it: denying the standing of any citizen not directly and personally concerned to challenge administrative decisions for excess of authority. Of course, this limitation undermines the right to access information and keeps many administrative actions out of the public’s sight, just as the administration has, via its narrow conception of interest, succeeded before the State Council in keeping many such actions away from any challenge.

The gravest aspect of this retreat or regression is that it comes at a time when the government is supposed to be making significant efforts to convince lenders and donors of its credibility in combating corruption. From this angle, this letter’s concurrence with these circumstances seems akin to a grievous attack on public interest and Lebanese society’s chances of overcoming its crisis.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Access to information law, Corruption, Administrative ethics, Lebanon