Judiciary Draft Laws in Morocco: Undercutting the Young Judges Movement

Judicial reform in Morocco has been a major item of discussion for decades on the agenda of the country’s reformist forces and legal rights activists. Many international reports have also expressed concern over how fragile the guarantees for the judiciary’s independence are in the context of Morocco’s existing legislative system.

However, demands for reform fell on deaf ears. This is because the consecration of an independent judiciary continued to be postponed under the pretext of settling other political, social, and economic issues that emerged in the wake of independence. These issues include the consolidation of state authority and stability, as well as the resolution of political rivalries.

The Arab Spring and the ratification of the new Constitution on July 1, 2011 brought life back into the debate. The Constitution provided, at least superficially, for several guarantees that would uphold the sought-after level of judicial independence. The challenge, however, is whether the Constitution’s provisions will be put into practice via the promulgation of regulatory laws -a crucial step in determining whether there is a serious political will behind the push for greater judicial independence- or it is a reflection of opportune political sloganeering.

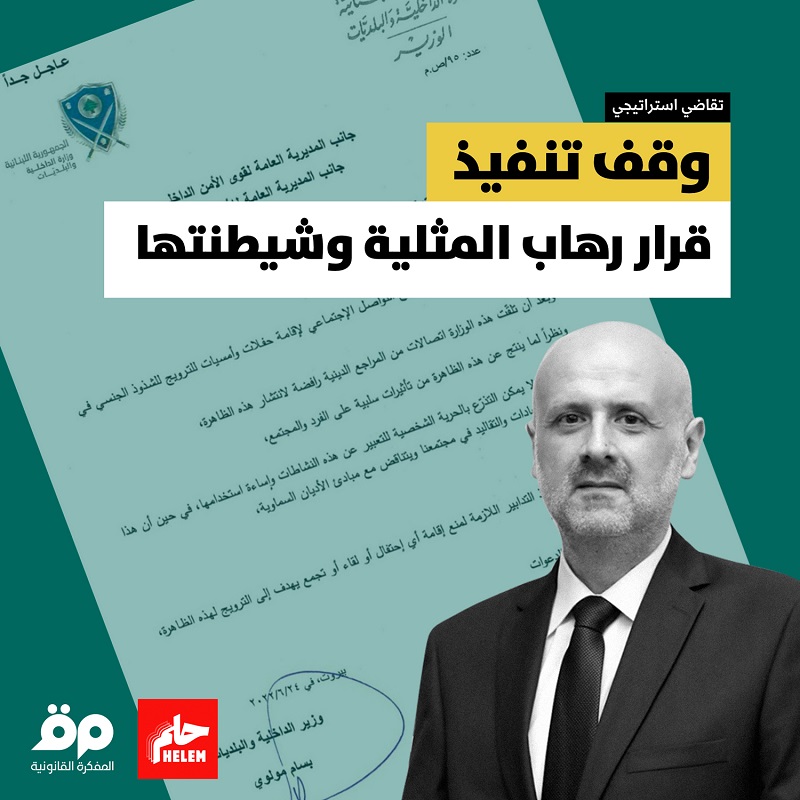

In this context, the Ministry of Justice and Freedoms published the draft statute for judges and a draft law governing the Supreme Judicial Council on the ministry's official website. The ministry invited the judges professional association to comment on the drafts no later than November 15, 2013. In what context did these draft laws emerge? And to what extent have these texts been able to genuinely reflect the content of the constitutional document, and lay the foundation of the independence of the judiciary in practice, and not in theory?

Draft Laws in Light of Judicial Stirring Activity

The draft laws announced in early November cannot be assessed in isolation of developments that took place in the realm of legal rights, both at the national level and the judicial one, following the ratification of the 2011 Constitution. Top among them is the emergence of new and effective actors, namely, judicial professional associations. These associations enhanced the status of the judiciary in Morocco as judges started to act more freely in public after breaking the illusory restrictions that some authorities tried to impose, in the name of the duty to refrain from public commentary or action.

The establishment of the Judges’ Club coincided with the emergence of a new generation of judges whose concerns and demands went beyond improving their financial conditions and focused on more pressing issues. These include the need to establish genuine guarantees of judicial independence at the individual and institutional levels. Several recent initiatives by the judges are best understood in the context of this emerging culture of demands. These include: the judges’ first-time boycott of training courses organized by the ministry; the boycott by a large number of judges of national dialogue seminars run by the Ministry; and, the judges' refusal to receive compensation for judicial supervision of elections, in the absence of a clear legal framework regulating the process.

These actions culminated in a national rally held by the judges dressed in gowns outside the Court of Cassation. Rally participants called on the Supreme Judicial Council to fairly address pending appointments and transfers, and to assert autonomy vis à vis the Ministry of Justice by recognizing the independence of the offices of Public Prosecutions and Judicial Administration.

Draft Laws Seeking To Contain Judicial Stirrings

In the last two years, three main factors have contributed to the emergence of the Moroccan judicial movement:

The constitutional and associational factor:

The July 1, 2013 Constitution advanced a set of progressive provisions related to judicial authority. While some of these provisions remained unimplemented pending the issuance of regulatory laws, others were put into practice by judges through their exercise of the right to freedom of expression, and the establishment of professional associations, the most prominent being the Moroccan Judges’ Club. This association practically ended the monopoly of [the state-sanctioned judges association] al-Widadiya al-Hasaniya in keeping judges under the fold of the Ministry of Justice.

Age and group factor:

A large part of the transformation that the judicial body underwent was mainly attributed to the role played by the young generation of judges calling for change, especially second and third degree judges who were new graduates from the Higher Judicial Institute.

The presence of these judges has been felt at every stage of the judicial movement, from the establishment of the first independent professional association to the carrying of protest badges by judges, to the aforementioned sit-in outside the Court of Cassation. Advanced means of communication and modern technology (mainly Facebook), as well as the new atmosphere of freedom of expression were contributing factors to this presence.

The main demands of this emerging movement for change among the judiciary may be summarized as follows:

Total [institutional] separation between the judiciary and the Ministry of Justice, and the transfer of the Minister of Justice’s powers to the body representing the judiciary (the Supreme Judicial Council), as well as strengthening the role of that body and subjecting the selection of its permanent members to a democratic process.

Financial factor:

Improvement of the financial conditions of judges, especially young judges of lower grades, and the reclassification of judges according to their seniority in the new grades and ranks within a more motivating promotion system.

A preliminary reading of the draft laws announced by the Ministry of Justice, however, confirms that these texts run contrary to the judges' expectations and reflect a genuine will to constrain and corner the judicial movement.

Hierarchy as a Tool to Subjugate Young Judges: The “Deputy Judge” Concept

On an individual level, draft laws under consideration have introduced new mechanisms to restrict young judges whose generation spearheaded the judicial movement in Morocco. The most serious action taken in this regard was the creation of a new category of judges known as the “deputy judge” -a temporary position bestowed on graduates of the Moroccan Higher Judicial Institute. A deputy judge is placed on probation for two years during which his/her immediate supervisor is in charge of assessing whether he/she is qualified to become a full fledged judge.

In effect, the Ministry seems to be employing judicial hierarchy as a means of discouraging new graduates from engaging in the judicial movement and transforming them into obedient members who follow instructions dictated by their immediate supervisors. Such a setup would reproduce a form of senior authoritarianism. In the past two years, the Judges’ Club has issued several communiques to expose attempts by senior judges to interfere in and influence the work of young ones. These attempts include violations of public associations, intervening in hot legal cases, applying pressure on [younger] judges to receive compensation for overseeing the elections, and discriminating based on associational affiliations.

Restricting Associational Activity and Prioritizing the Social and Cultural Demands Over Those for Independence

On an institutional level, the draft laws regulating the judiciary restrict the right of judges to directly establish associations and, in general, limit their activities within associations. One of these restrictions introduced by the new draft laws is Article 86. This article stipulates: “a judges’ association shall have no less than 300 members, drawn from at least 15 different courts of appeal districts, with a minimum of five members, including a female judge, per district”. This stipulation strips a number of professional associations of the right to exist and restricts the right of judges to establish new ones. It also aims to prevent judges from establishing regional associations.

While the draft law mentioned above outlined detailed regulations concerning the make-up of associations -a task generally reserved to the associations themselves- it was devoid of any provisions to ensure the democratic functioning of such associations. Strikingly enough, one of the draft provisions (Article 89) makes it easier for anyone with a stake to submit a request to dissolve any of these associations, while limiting the jurisdiction of looking into appeals to the administrative chamber of the Court of Cassation exclusively. This is a flagrant violation of the principle of litigation on two levels.

Moreover, while the new draft law tried to regulate the establishment and dissolution of judges’ associations, it failed to address the roles and functions of these associations. This is reflected clearly in Article 85 of the draft statute for judges, which limits the objectives of the associations to encouraging meetings, discussions and seminars, and improving the judges’ social and cultural status. The remaining articles of the draft statute fail to highlight actual functions, such as disciplinary action, delegation, and election of the Supreme Judicial Council. It appears as if the draft statute aims to limit the role of these associations to social and cultural aspects without any reference to their role in defending the independence of the judiciary, or in the formulation of its rules of conduct.

Lastly, the draft statute explicitly prohibits judges from establishing trade unions and criminalizes strikes, considering the latter a violation of professionalism that warrants disciplinary action.

Undermining Independence: Housing, Transfer, and Appointments

The draft laws submitted by the government to regulate the judiciary fall short of corresponding international standards. One example is the stipulation that judges have to reside within the area falling under the jurisdiction of the courts they serve. The law does not require the state to arrange for decent housing or provide housing allowances, as is the case with the statute of judges in Algeria (Article 20) and Yemen (Article 70). Morocco’s new draft laws have also failed to enshrine job security for judges and safeguard their independence. Promoting a judge, for instance, is seen as a sufficient excuse for transferring them -a practice which when used [for political ends] turns the blessing of a promotion into a curse.

The draft laws adopt a conservative approach regarding the individual status of judges. Article 60 of the draft law regulating the Supreme Judicial Council stipulates that the Council shall observe the principles of equal opportunities, merit, efficiency, transparency and impartiality. However, the application of this text remains general and devoid of any reference to tangible, objective criteria such as the entitlement of Higher Institute graduates to be appointed as judges.

Delegating Judges to “Resolve a Legal Case”

Delegation is another shortcoming in the new draft laws prepared by the Ministry of Justice. Although the power to delegate judges was transferred from the minister of justice to one of the assigned court presidents (President and Crown Prosecutor General at the Court of Cassation, presidents of first divisions, and prosecutors general at courts of appeal), the mandate was too general to prevent the use of this mechanism for settling scores or as a way to undermine judicial independence. In this respect, Moroccan draft laws fail to provide guarantees to judges referred to by the laws of Arab countries. For example, Jordanian law stipulates that, in the case of delegation on a mission or assignment of a task, the judge shall not suffer a demotion in degree. Under Egyptian law, a delegation requires the approval of the judges’ general assembly at the competent court.

More alarmingly, Article 37 of the draft law regulating the Supreme Judicial Council states that “the first president of the Court of Cassation or the Crown Prosecutor General therein may delegate within their jurisdiction a judge to fill the vacancy in one of the courts. Also, first presidents of courts of appeal and two crown prosecutors can delegate within their jurisdiction a judge to participate in deciding on a legal case or fill a vacancy in one of the courts within the jurisdiction of these courts”.

Concerns have been raised about the phrase “the delegation of a judge to decide on a legal case”, particularly with regard to the concept and purpose of such a delegation, the type of case that requires the delegation of a particular judge, and whether that would affect the course of the case in favor of the party commissioning this judge. In this regard, the years of conflict [known as the “years of bullets” between the 1960’s and 1980’s] when judges or sometimes judicial bodies were delegated to decide on specific cases come to mind.

Hierarchy in Lieu of Equality; Exclusion in Lieu of Partnership

The draft laws in question reflect a narrow-minded way of thinking and clearly show a desire to stoke up hierarchies within the judicial body, by setting the requirement of five-year seniority to run for the membership of the Supreme Judicial Council. They concentrate power in the hands of judicial officials who play a key role in promotions, while undermining partnerships by marginalizing any prospective role of public associations, court judges, and young judges who have come to represent [for these powers of the status -quo] a movement that should be eradicated.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.