Interview with Lebanon’s Islah Dhat al-Bayn: Are Women’s Issues Hostage to Ideological Pluralism?

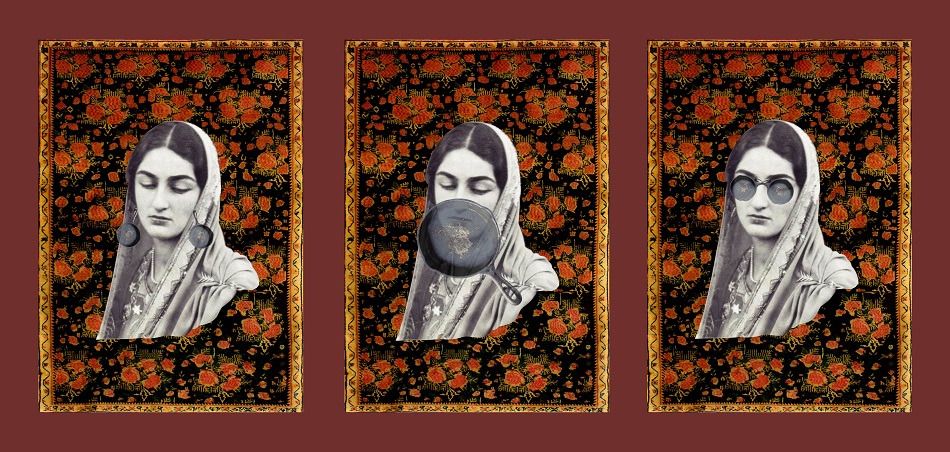

With the proliferation of organizations working on women’s issues in Lebanon, a multitude of ideologies, frames of reference, discourses, approaches, and methodologies have emerged. This plurality has undoubtedly led to disagreements among these organizations over several points of reform that have been put to public debate. Given the dominance of secular women’s groups over the public discourse on women’s issues, in this article the Legal Agenda is shedding light on the work and approach of Islah Dhat al-Bayn [Reconciliation] , an organization working “under the umbrella” of Dar al-Fatwa [the highest official religious Sunni authority] on issues concerning women (and the family) from an Islamic standpoint. We interviewed the organization’s president, Maha Fatha.

Legal Reform: Between “Realism” and the Civil State

Many secular organizations work on passing civil laws concerning women. These laws usually address a woman as an individual, and these organizations usually adopt the international laws and agreements that Lebanon has ratified as their frame of reference. As for Islah Dhat al-Bayn, it works on proposing amendments to Sunni religious laws. However, its fundamental goal is to secure and strengthen family stability by educating people intending to marry and mediating between spouses when disagreements arise, and this is the clearest theme of its pamphlets.[1] Hence, the difference between the organization and the secular feminist current in their approaches to personal status is clear. While the secular feminist current links personal status to individual rights and argues that women must be “liberated” via civil legislations, Islah Dhat al-Bayn focuses on the concept of family in particular and links its understanding and work on women’s issues to the framework of the family system.

The difference between Islah Dhat al-Bayn and the secular current in the methods of reform adopted is also clear. The secular feminist organizations direct their discourse and energies primarily toward the Lebanese state to induce it to perform its duty to regulate its citizens’ affairs, and some even refuse to deal or work with the sects’ institutions. Islah Dhat al-Bayn, on the other hand, focuses its work on the Sunni sect’s system and institutions, aiming to improve them from within while still participating in parliamentary debates when necessary. The religious organization explained its positioning via “realism”: “We’re saying to girls and our organization, stay where you can do good; outside, you won’t be able to do any good”. This “realistic” approach resembles approaches previously adopted by other movements within the Sunni sect, particularly the Family Rights Network, which achieved several demands (including raising the age of maternal custody) in 2012 after the women went “directly and exclusively to the Sunni sectarian authority and its laws while ignoring the state”.[2]

The Islamic organization’s work is based on an acceptance of what it described as a sectarian reality that will not change any time soon given Article 9 of the Constitution (note that Article 9 guarantees the right to sectarian legal pluralism specifically, not the “sectarian reality” as a whole).[3] From this standpoint, work and reform must occur within the Sunni sect rather than at the level of the central state, though statements in the interview like “sectarianism is a scourge” show that this acceptance does not preclude any critical approach to reality. The “realistic” approach appears in statements like, “What’s important isn’t what we want – we’re realists”. Fatha also began many of her arguments by saying, “as long as Article 9 of the Constitution protects the sects”, meaning that the organization works within the bounds set by “the Constitution” and reform is possible inside the space made available for it, namely the Sunni sect.

Islah Dhat al-Bayn: An Arm of Dar al-Fatwa or a Movement for Reform from Within?

Despite the close connection between Islah Dhat al-Bayn and its religious sponsor, Dar al-Fatwa, the relationship was not without issues according to the discourse of the organization’s president. This organic tie with the Sunni religious institutions does not protect the organization from pressures and resistance to it. During the interview, we perceived that the support the organization has obtained from Dar al-Fatwa and the sectarian courts came with a certain degree of apprehension toward it. In this regard, Fatha recounted the apprehension that the organization faced in the early stages of its work in the Islamic courts, which prompted it to formulate a charter defining its responsibilities and the scope of its work in order to alleviate the fears of judges and lawyers in the Islamic courts. However, statements like “they resisted us a lot” in reference to a custody case that the organization worked on and that stirred controversy within the Islamic courts and Fatha’s hesitation when we asked about any resistance from lawyers and judges in the Islamic courts today all suggest that the apprehension from within toward Islah Dhat al-Bayn still exists. Fatha also mentioned that although the organization is subordinate to Dar al-Fatwa, it receives no financial support, which is evidence of the caution in the institution’s approach to the women’s organization. Regarding the organization’s legal work, it emerged in the interview that the actors in Dar al-Fatwa refuse to have any women (from the organization or otherwise) on the Committee for Amending Laws (i.e. the personal status law-making committee in the Sunni sect), and the organization’s role has been restricted to submitting non-binding proposals to the committee. Hence, the scope of its legal work remains limited.

When it comes to women’s and family issues, the organization’s views do not line up completely with Dar al-Fatwa’s views, though the organization’s public stances suggest otherwise. In this regard, Fatha supports state intervention on domestic violence and the need for a law against it despite Dar al-Fatwa’s opposition to the law since Grand Mufti Mohammed Rashid Qabbani’s statement in June 2011. However, she expressed this support extremely cautiously and after giving examples of women who concocted hoaxes to portray their husbands as abusers, thereby returning to the old hypothesis that the law threatens the integrity of the family. Fatha also emphasizes the need to establish a social fund for domestic violence victims and the “flaw” in the current law that must be amended, namely its insufficient focus on rehabilitating abusers after prison: “[Roumieh prison] is a factory for criminals; a person might enter on account of a bad check or something trivial and emerge an expert in everything”.

As for the marriage of underage girls, Islah Dhat al-Bayn expressed its rejection of the phenomenon and supported the need for a law setting the minimum age for marriage and punishing anyone who allows child marriage to occur. Fatha mentioned that, “In the Sunni sect, when they set the age of [maternal] custody to 12, they said that at this age, a boy can study by himself. Okay, so can someone start a household by herself before the age of 18 or have a child? Even medically, childbearing between the ages of 20 to 30 is better for protecting the woman”. Moreover, the interview showed that the Islamic organization supports punishing clerics who perform child marriages: “Whoever performs a customary marriage [involving an underage girl] must be punished and the punishment redoubled. What do they give him – 100 or 200 thousand [Lebanese liras in fines]? No, he must be imprisoned”. Regarding exceptions in the law, the organization deems that the power to grant exceptions should be left in the hands of the religious authorities and that this approach stems only from a sense of realism and Article 9 of the Constitution, not any other justification: “As long as Article 9 of the Constitution protects the sects, I think that if there must be an exception, it should be given by a religious court judge”. Fatha stressed the need for the girl to be referred to a gynecologist and psychologist before the religious judge permits an exception. Additionally, the organization expressed no desire to place exceptions in the law, but it deemed that “if there must be an exception”, the process should occur “realistically”.

“Inside” and “Outside”: The Secular Sphere Versus the Religious Sphere

The “schism” that exists today between the civil current and the religious current manifests itself in the organization’s discourse via the terms “inside” (in reference to the Sunni sect) and “outside” (in reference to the overall legal system). While the secular current links women’s issues to a general debate about rights and freedoms under the sectarian system and the tension between the civil and religious currents, the discussion with Islah Dhat al-Bayn was limited to the issues that it works on directly. Usually, the secular feminist current claims a monopoly over law and legal discourse, portraying the religious sphere as one governed by “non-legal” values. It thereby denies the legal nature of religious laws, strips the religious sphere of any legal aspect, and, subsequently, obscures the legal pluralism whereby citizens can be subject to several legal systems.

Given this schism, we must also note the “civil” characteristic that Fatha finds in the religious sphere, particularly within the Sunni sect. “I believe that our laws are civil”, she saidsays when talking about the Sunni marriage contract, which is “civil” in the sense that it can contain whatever agreed-upon conditions the spouses please. She gave examples of how the contract can preserve the wishes of the wife in particular. She stated, “This is not a fixed contract. Since you can change things in it, this is a civil contract”.

When we asked Fatha why the organization confines itself within the scope of the Sunni sect and has not joined feminist currents working on the state level, she answered clearly that it is unwanted by these currents: “If we want to enter, they shun us”. Moreover, it is apparent that the two “spheres” have a narrow conception of feminism: on one hand, the secular current virtually monopolizes feminism, and on the other, the religious current displays caution toward the concept as Islah Dhat al-Bayn avoids the term. “I defend women, but without being called a feminist – I don’t want a label”, saidsays Fatha in reference to feminists’ bad reputation of support for “separating women from men and destroying the family”.

The Future of Feminist Action in Lebanon: What Are the Chances of Shared Spaces?

In the journal article “Secular and Religious Feminisms: A Future of Disconnection?”, researchers Dawn Llewellyn and Marta Trzebiatowska argue that it is not enough for feminist currents not to oppose the approach of the other feminist currents; rather, they must accept each other and recognize each other’s legitimacy in order to foster shared citizenship in democratic societies.[4] Alongside these researchers and in light of this interview, we ask – without downplaying the challenges – does feminist reform remain hostage to the “conflict” between the secular and religious spheres? Or is it breaking free via feminist currents’ recognition of the legitimacy of each other’s approaches, even if they differ to one extent or another?

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Lebanon, Feminism, Secular feminist, Religious sphere, family law, Islah Dhat al-Bayn

[1] Islah Dhat al-Bayn’s booklet states that its goals are “working to achieve family stability, protecting the family from any threat, raising young people’s awareness and educating them about choosing a spouse, providing family guidance to people getting married for the sake of a successful marriage, and fostering a culture of cooperation and bonding within the family”.

[2] Samer Ghamroun, “Lebanese Personal Status Laws: The Struggle in Sunni Courts”, The Legal Agenda, is. 62.

[3] Article 9 of the Constitution, which grants the sects the power to regulate themselves in the realm of personal status, states:

There shall be absolute freedom of conscience. The state, in rendering homage to God Almighty, shall respect all religions and creeds and shall guarantee under its protection the free exercise of all religious rites provided that public order is not disturbed. It shall also guarantee that the personal status and religious interests of the population, to whatever religious sect they belong, shall be respected.

[4] Dawn Llewellyn & Marta Trzebiatowska,. “Secular and Religious Feminisms: A Future of Disconnection?”, Feminist Theology, vol. 21, is. 3, 2013, p. 244–258.