In the Name of the Palestinian People: Court Abrogates Oslo Accords

On January 11, 2015, Ahmad al-Ashqar, a judge in the Penal Department of the Jenin Magistrate Court in the West Bank , issued an atypical ruling in a criminal case. This ruling decreed that the Oslo Accords are no longer in force. As a result, Israeli nationals are no longer exempt from prosecution by Palestinian courts as stipulated by the Accords.[1]

Palestinians applauded the ruling and the judge who issued it.[2] Al-Ashqar was seen as a pristine, independent voice within the Palestinian National Authority (PA),[3] a voice expressing the impartiality of the judicial establishment and concerned with the day-to-day issues that Palestinian citizens have long endured.[4]

However, the joy did not last long. Within a week, the head of the Jenin Court Judge Kamal Jabr transferred al-Ashqar out of the criminal department to work as an implementation judge. Jabr claimed the transfer was due to work-related pressures and requirements.[5]

The incident reflects the close association between a judge’s social role and their judicial independence. The further a judge’s rulings deviate from the preferences of the political authorities, stereotypical social views and prejudices, the greater the threat to their independence and the greater the need to consolidate such independence. The fact that the judiciary directly confronted the occupation adds to its importance. The following report is an attempt by The Legal Agenda to document and analyze the incident in order to further understand Palestinian judicial independence during the phase of state building under occupation.[6]

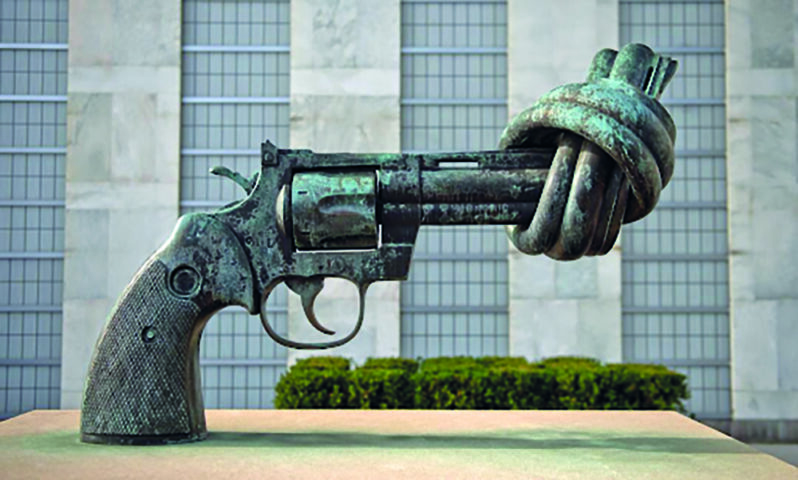

Challenging Oslo

Al-Ashqar’s ruling came in response to a plea put forth by the defense arguing that the court had no jurisdiction over the case. Palestinian courts, the defense argued, cannot try those who hold “the occupying state’s nationality”. The text of the ruling addressed two issues. Firstly, it determined that Palestinian courts have jurisdiction to try anyone who commits a crime on Palestinian National Authority soil, whatever their nationality.[7] It based this conclusion on the Jordanian Penal Code of 1960, which is in force in the West Bank.[8] The second and more delicate issue that it addressed is the aforementioned exemption from the jurisdiction of Palestinian criminal courts that the Oslo Accords granted Israeli nationals.[9]

Using his discretionary power, al-Ashqar resolved this issue by rejecting the accused’s plea on the basis that the Oslo Accords have legally expired.[10] This he explained by saying that, “in its nature as an interim, limited-term agreement restricted to the arrangements of the transitional phase that extended five years from the date that it was put into force, the Oslo Accord carried the seeds of its own demise. None of the subsequent agreements extended the Oslo Accord, neither openly nor implicitly”.[11] Hence, he concluded that the effective term of the Accords ended several years ago.

The judge also argued that recent recognition of Palestinian statehood has created a new legal reality that supersedes the Oslo Accords, and puts Palestine in its rightful place in international law.[12] He noted that, “Palestine has obtained observer state status in the UN and, in this capacity, signed international agreements and conventions, the latest of which was the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court”.[13] Hence, Palestine has become “a completely sovereign state under occupation, a state administered by a government and authorities emanating from Palestinian statehood, not from the Interim Self-Government Authority created by the Oslo agreement. The occupation’s presence on Palestinian soil does not detract from this because occupation does not remove sovereignty, as international law has established. This means that the Palestinian state has legal sovereignty over Palestinian soil, as it has transcended the temporary, objective conditions that the Oslo Accord imposed upon it as an interim authority”.[14] The ruling affirmed that “the jurisdiction of the Palestinian courts is derived from the sovereign Palestinian people’s right to exercise authority in their state, and over their territory through the three powers [of government], in accordance with Article 2 of the 2003 Amended Basic Law. This includes the judicial power entrusted to the courts in all of their different kinds and levels, which judge in the name of the Arab Palestinian people”.[15]

The mandating reasons of the ruling are remarkable. On one hand, they demonstrate an innovative way to strategically use the law and the court system to set the wheels of political and social change in motion. On the other hand, they show how the Palestinian courts can be harnessed as a means of resistance by putting the occupation on trial, and as a means of rejecting the deteriorated state of affairs that has long frustrated all sections of Palestinian society.[16]

The ruling is doubly important due to the current political situation marked by intentional and repeated efforts to thwart the peace process, an Israeli occupation that treats Palestinian lives and property as fair game, refusal by the Security Council to adopt a resolution to end the occupation, and repeated threats by Palestinian Authority head Mahmoud Abbas to dissolve the PA. Given these circumstances, the ruling expressed the status of a society exhausted by the scourge of war, the occupation’s practices, and the lie of peace, the search for which has become a search for the impossible.

At the grassroots level, the ruling gave rise to a spirit of hope among the Palestinian public.[17] The Palestinian court system, as a national institution, was conceived as an instrument of reason and law to help resist the occupation.[18] Many Palestinians found in the court an independent, impartial, and honest voice speaking in their name and questioning the effective validity of the Oslo Accords now that Palestine has attained non-member observer state status in the UN General Assembly,[19] and signed the Rome Statute, thereby joining the International Criminal Court.

Al-Ashqar’s ruling is the first to declare the Oslo Accords null in the context of a criminal case. However, many previous rulings made by Palestinian civil and religious courts have harnessed the language of law to refuse to cooperate with the occupation system, and to consolidate the diverse means of struggle available to the Palestinian people.[20]

The removal of the issuing judge from his position was equally remarkable in that it raised important questions about judicial independence in the desired Palestinian state.

Judicial Independence in Wonderland

Days after al-Ashqar’s ruling was published, the head of the Jenin District Court, to which al-Ashqar is subordinate, issued a written decision that transferred him out of the Penal Department to work as an implementation judge. The latter type of judge carries out rulings, but has no jurisdiction to issue them.[21] In a written explanatory statement that followed, the High Judicial Council justified the reassignment on the basis of work requirements, and the fact that it does not affect the judge’s standing.[22] However, the statement did not shy away from commenting on al-Ashqar’s ruling, implicitly acknowledging that it is connected to the reassignment. After mentioning that magistrate court rulings cannot form legal principles and can be contested via appeal,[23] the statement criticized the ruling’s mandating reasons that related to the Oslo Accords and the prosecution of Israelis; “A magistrate judge”, it stated, “cannot make a final decision about whether or not the Oslo agreement is still in force, because this is a political matter to be decided by the Palestinian leadership, not a judicial body of any form”.[24]

Palestinian public opinion was shocked by the reassignment and the justification that the High Judicial Council provided.[25] The ruling undermined the population’s trust in the impartiality and independence of the judiciary, and highlighted the amount of meddling and pressure imposed upon it.[26] The repercussions of the transfer garnered more attention than al-Ashqar’s original criminal ruling.[27] Ammar Dwaik, professor of political science at Birzeit University, saw the transfer decision as undermining the sanctity of judges’ rulings, and a blow to the faith citizens have in state institutions.[28] In his view, it is a punitive decision based on politics, not judicial considerations. It also sends an intimidating message to judges –especially young ones– that they should not rely on discretion in their rulings.[29] The reassignment also disillusioned law students in Birzeit’s Faculty of Law and Public Administration. The students have come to doubt the rule of the law and its efficacy under a judicial council that thwarts the potential and abilities of judges. These students launched a social-media campaign of solidarity with al-Asqar (“We Are All Ahmad al-Ashqar”). In the words of one of them, “I don’t know why I study law in a country where law doesn’t exist in the first place. As though the occupation weren’t enough, here we are facing off against each other. Honestly, the law is one big lie”.[30]

A number of attorneys also voiced their disapproval of the judicial authorities’ performance and the deteriorated state of the judiciary, which suffers from politicization and subordination to political parties, especially Fatah.[31] They also expressed their displeasure about the failure of the Palestinian Bar Association to take a serious stance on the poor state of the judiciary and its lack of independence. One attorney mocked the reassignment, exclaiming, “Behold the lofty judiciary! The court has quickly transferred Judge al-Ashqar to the implementation department so that he can implement his ruling!”.[32]

Moreover, the Palestinian Center for the Independence of the Judiciary and the Legal Profession (Musawa) composed a memorandum to the Council in which it objected to the reassignment. It stressed that judges should not be punished for applying the law. The executive director of the center criticized the Council’s statement by explaining that it failed to express good policy in judicial authority, and reflected the judicial administration’s lack of faith in its judges.[33]

A similar view was held by a group of lawyers who, in a statement to The Legal Agenda, expressed reservations about al-Ashqar’s ruling and the media coverage it engendered, which treated the issue like a scoop. Although they criticized the personification of judicial work reflected by this case and the desire of some judges to attain stardom at the expense of their work, they did not approve of the High Judicial Council’s behavior or the language of its explanatory statement. The Council’s move, they believe, encroaches on the work of the courts. That these lawyers asked The Legal Agenda not to mention their names is very telling of the amount of pressure they face within the legal system.

Conclusion

The High Judicial Council’s explanatory statement is a living example of its interference, and the interference of the Palestinian leadership in the work of judges. Declaring that a judicial body cannot make a decision that is the prerogative of the Palestinian leadership strips judges of all authority in matters of a political nature. It is worth noting that under the occupation, almost any matter has the potential to turn political. Furthermore, the statement sends a message that will deter any judge who may want to do more than serve the laws put in place by political authorities, or step beyond the limits those authorities impose. From this perspective, al-Ashqar’s reassignment is a punitive decision in disguise, and a lesson from the Council for every judge who may be “seduced” into deviating from the norm by thinking about different ways to analyze and use the law.

The haste with which the High Judicial Council reacted to al-Ashqar’s ruling and the sharpness of its rhetoric also suggests that the Council, and perhaps the executive government authorities, are afraid that a culture of judicial discretion could spread in socio-legal cases, including cases that have political repercussions. Such a development could turn the courts into a social space for discussing issues that impact the daily lives of all Palestinians, issues that have long been ignored or concealed by the Palestinian leadership.

It is important to keep the socio-political context of the al-Ashqar case in mind. In a society searching for some form of sovereignty while trapped by the clutches of an occupation, the Council’s actions may be read as an urgent and decisive measure to close the door on any change that any of the vital issues in Palestinian society could provoke. Such issues include the question of the Oslo Accords’ validity, as well as the questions of how to deal with the occupation, the settlements, the seizure of land and property, the erasure of the Palestinian identity, and the inability of the Palestinian Authority to exercise any form of sovereignty under the occupation, or end the blockade that has been imposed on the Gaza Strip since 2009.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] Jenin Magistrate Court, criminal case no. 855, 2014.

[2] See: Ibrahim Anqari’s, “Jenin Magistrate Court’s Refusal to Apply “Oslo” Affirms Sovereignty”, Al-Watan, January 12, 2015.

[3] See: Awad al-Rujub’s, “Ruling to Abrogate Oslo Removes Judge from his Position”, al-Jazeera, January 19, 2015.

[4] A number of attorneys and academics welcomed this ruling. Among them were Shawan Jabarin, director of Al-Haq, Mutaz Qafisheh, dean of the law college at Hebron University, and Ghandi Raba’i, director of the Monitoring of National Legislation and Policies department in ICHR.

[5] Explanatory statement from the Judicial Media Centre, available on the High Judicial Council’s website, January 26, 2015.

[6] This article does not aim to study in depth the decision to consider Oslo legally invalid as the matter is still subject to appeal.

[7] To this day, the lack of legislative coordination remains a problem in the Palestinian legal system. There is still no unity in the legislation of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem. For example, the Jordanian Penal Code, which applies in the West Bank, differs from Penal Code No. 74 of 1936, which applies in Gaza.

[8] Article 7 of the Jordanian Penal Code No. 16 of 1960, published on page 374 of issue 1487 of the Official Newspaper, May 1, 1960.

[9] Specifically, the text of Article I, point 2b of Annex IV (Protocol Concerning Legal Affairs), Oslo II (Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip), which plainly exempted Israelis from the jurisdiction of Palestinian criminal courts.

[10] The text of the Jenin Magistrate Court’s ruling in criminal case no. 885 of 2014.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Shawan Jabarin , director of Al-Haq, quoted in Maan Samara, “For the First Time Since Oslo’s Signing, Jenin Magistrate Court Annuls and Refuses to Apply It”, January 11, 2015.

[17] Ghandi Raba’i, director of the Monitoring of National Legislation and Policies in ICHR, in an interview with Awad al-Rujib, al-Jazeera, January 19, 2015.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Mutaz Qafisheh, dean of the law college at Hebron University, quoted in Maan Samara, “For the First Time Since Oslo’s Signing, Jenin Magistrate Court Annuls and Refuses to Apply It”, January 11, 2015.

[20] One example is the judicial ruling to profile the occupation’s policies of fragmenting Palestinian territory in the Court of Cassation case no. 111 of 2012; another example is case no. 812 of 1997, which investigated the issue of referring Palestinian criminals to the enemy’s courts.

[21] Explanatory statement from the Judicial Media Centre, the High Judicial Council, January 18, 2015.

[22] Article 2, ibid.

[23] Article 3, ibid.

[24] Article 4, ibid.

[25] See: “The High Judicial Council Punishes Judge Who Ruled Oslo Invalid”, Palestinian Press Agency, January 19, 2015.

[26] Ibid.

[27] See: Awad al-Rujub’s, “Reassignment of Judge Who Ruled Oslo Invalid Worries Palestinian Street”, al-Jazeera, January 21, 2015.

[28] See comments by Ammar Dwaik in an interview in ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Law student, Faculty of Law and Public Administration in Birzeit University, January 20, 2015.

[31] Comments from lawyers on the Facebook page “Guardians of Justice”.

[32] This comment was circulated on the Facebook page “Palestinian Lawyers”.

[33] See: Ibrahim al-Barghouti in an interview with Awad al-Rujub, “Reassignment of Judge Who Ruled Oslo Invalid Worries Palestinian Street”, al-Jazeera, January 21, 2015.