Human Trafficking in Lebanon: A Shocking Reflection in the Mirror

In late March 2016, Lebanese citizens got a first-hand encounter with the act of human trafficking. Approximately 75 women had fallen victim to a ring that took advantage of their vulnerability and destitution to impose upon them exploitative conditions from which they could never break free. The field of exploitation was prostitution: large numbers of customers took pleasure in the ring’s services and often conspired to turn a blind eye to the exploitative relations that prevailed inside the ring’s venues, or to keep the exploitation concealed.

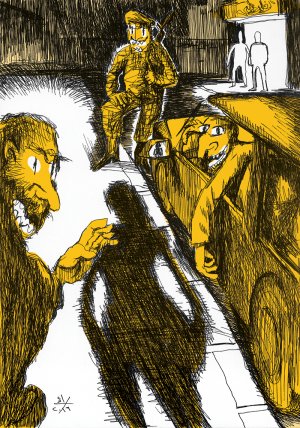

Before the ring was exposed, human trafficking in Lebanon appeared to be a theoretical issue or, at best, an agenda item imposed by American pressure. Following the ring’s exposure, the Lebanese public [and prominent members of the political class] seemed shocked by the tragedies that the women had experienced as a consequence of being trafficked. In reality, this shock reveals great ignorance of not only the prevailing social systems that underpin human trafficking or at least facilitate it, but also the reality that now exists because of the proliferation of all kinds of marginalization and exploitation. In another article, I labeled this proliferation “the manufacture of vulnerability”.[1] From this perspective, the shock occurring is, in essence, that of a person surprised by the sight of his own true features in the mirror. In the face of this scandal and shock, three main observations can be made:

Ignorance of the circumstances of human trafficking victims appears to persist even though a law criminalizing the practice was issued five years ago. The main reason for this persistence may be that the law was drafted as a result of foreign and international pressure in the absence of any social discussion or demand. This is clearly evident in the law’s mandating reasons and the speech made by then-Minister of Justice Shakib Qortbawi during the parliamentary debates: “We are passing through harsh circumstances and eyes are on us…and [the law’s adoption] is a very important message to the international community.” On the other hand, Qortbawi’s speech made no reference to the current status of human trafficking victims in Lebanon. Furthermore, one of the ministers of the government that adopted the bill confirmed in a private interview with The Legal Agenda that most of the ministers were, at the time, convinced that this law was needed to fend off international pressure and that it would not be applied in reality. Thus, despite the significance of this law, which for the first time added a criminalization of exploitative relations to the Penal Code, the face of the victim remained completely obscured. The circumstances surrounding the adoption of this law thereby differed entirely from those surrounding the adoption of the law for protection from domestic violence. The latter took place amid wide public discussion. As a result, the human trafficking law was rarely invoked while the violence against women law provided rich material for court jurisprudence as soon as it was issued.

No review of the other legislations that underpin or facilitate human trafficking occurred, even though sharp international criticism had been directed towards Lebanon on account of them. Hence, the Lebanese legal system is now in a state of contradiction: on the one hand, there is a law criminalizing human trafficking, but on the other hand, there are administrative decrees and regulations that open the doors to it and, to a large extent, constitute a part of Lebanon’s tourism policies. The most important of the latter may be the decree governing the conditions of entry for foreign male and female artists into Lebanon and their residence in the country. These directives were issued on August 6, 1962, in conjunction with the internal directives that the General Directorate of General Security developed to regulate the professions of female “artists” [as foreign sex workers are officially called]. These directives target, in particular, the approximately 3,000 female “artists” who enter Lebanon each year and work in “super nightclubs”. I explained in an earlier study how these directives subjected the residence of female “artists” to moment-by-moment control (encompassing their dancing hours, sleeping hours, and hours for “outings” with supposed clients), strictly limiting their freedom to even roam the hotel floor.[2] These so-called artists stay in Lebanon for a [legally-dictated] maximum period of six months, which is how long it takes to pay the debts stemming from the transactions associated with traveling to and from Lebanon and residency within it. Consequently, they usually stay within the same exploitation ring and must relocate with it to work in another country.[3]

Another issue is the sponsorship system, especially in the field of domestic work.[4] This system ties the legality of a worker’s residence in Lebanon to their employment with a specific person. It not only facilitates human trafficking, but also conceals its hallmarks. This is because a [foreign] worker in Lebanon enters an illegal status upon leaving her job, which in practice limits her options and forces her to submit to the work conditions, however harsh, in order to maintain her chances of staying in the country. These work conditions may include forced labor (one of the forms of exploitation that constitute human trafficking) and the restricted freedom associated with it. Worse, the sponsorship system often forces these workers to make an immoral trade-off between their right to justice as human trafficking victims, and the privilege of sponsorship, controlled by their employers, in order to stay in Lebanon. This occurs when a worker abandons a claim of non-payment of wages, sexual exploitation, or beating by her employer in exchange for his relinquishment of his right as sponsor to a new employer. Of course, such settlements occur under the noses of security and judicial apparatuses without evoking any reaction from them.

There is a deficiency in the work of the security and judicial apparatuses for going after human trafficking. To begin with, the Judicial Police’s competence to fight such crimes is restricted to a single security apparatus: the Anti-Human Trafficking and Morals Protection Bureau. Naturally, this makes it easy for personal interests and corruption to interfere with decisions to prosecute, as revealed by several reports.[5] The role of such corruption was again revealed when the latest ring was uncovered, for the escaped girls had decided to seek refuge with Hezbollah in order to circumvent the corruption within the security apparatuses, which had handed them back to the ringleaders after an earlier escape.[6] Perhaps the best evidence of the aforementioned deficiency is the small number of human trafficking cases –no more than 18– pending before the criminal courts in Beirut and Mount Lebanon today, even though five years have passed since the human trafficking law’s issuance.

The files for the human trafficking cases that we were able to examine in the criminal courts of Beirut and Mount Lebanon pertain to instances of family-related or individual exploitation (such as a husband prostituting his wife or a mother making her children beg). The prosecution of instances of collective trafficking, such as prostitution rings, remains very uncommon: only one of the 13 cases that The Legal Agenda viewed involved such trafficking. When a raid does occur, it ends in the prosecution of the victims for the crime of prostitution or illegal residence; the ringleader, on the other hand, usually escapes. This indicates the lackluster investigation and prosecution of major exploitation rings.

Hopefully, the atrocities of the latest case will redeem the victim as the rightful subject of this law and help drive its effectuation. Just as the case of [domestic violence victim] Roula Yaacoub provided key impetus for the adoption of the violence against women law, it is hoped that the case of the 75 women will be an incentive to let the human trafficking law out of its bottle.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] See: Nizar Saghieh’s, “Manufacturing Vulnerability in Lebanon: Legal Policies as Efficient Tools of Discrimination”, The Legal Agenda, Issue 25, February 2015 (published in English on March 19, 2015).

[2] See: Nizar Saghieh and Nayla Geagea’s, Legal Interpretation of the Status of Sex Workers with Regards to the Risk of Transmission of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), January 2009, produced in cooperation with SIDC, unpublished.

[3] Ibid.

[4] See: Rola Abimourched and Ghada Jabbour’s, “Lebanon, Country of Domestic Servitude, Once Again Under the Spotlight”, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 6, October 2012 (published in English on October 31, 2012); This article is a commentary on the report issued by UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, Gulnara Shahinian, on September 9, 2012, following her visit to Lebanon.

[5] See: Karim Nammour’s, “Methods of Torturing Vulnerable Groups in the Human Rights Watch Report: Vulnerability as a Gateway to Torture; What Recommendations for Reducing this Vulnerability?”, published on The Legal Agenda’s website, August 5, 2013.

[6] See: Rania Hamzeh’s, “Women Trafficking in Lebanon: The Torture Chambers of Chez Maurice”, published on The Legal Agenda’s website, April 1, 2016 (published in English on April 14, 2016).

Mapped through:

Articles, Asylum, Migration and Human Trafficking, Lebanon

Related Articles